Physics in the pandemic: ‘Our habit of combining theory and experiments was an advantage for the lockdown’

by Margaret HarrisTiphaine Kouadou is a PhD student who is supposed to finish her dissertation this year and Mattia Walschaers is a CNRS research scientist. Both work in the multimode quantum optics group at the Laboratoire Kastler Brossel (LKB) in Paris, France, which is affiliated with Sorbonne Université, CNRS, ENS Université PSL, and Collège de France. This post is part of a series on how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the personal and professional lives of physicists around the world. If you’d like to share your own perspective, please contact us at pwld@ioppublishing.org.

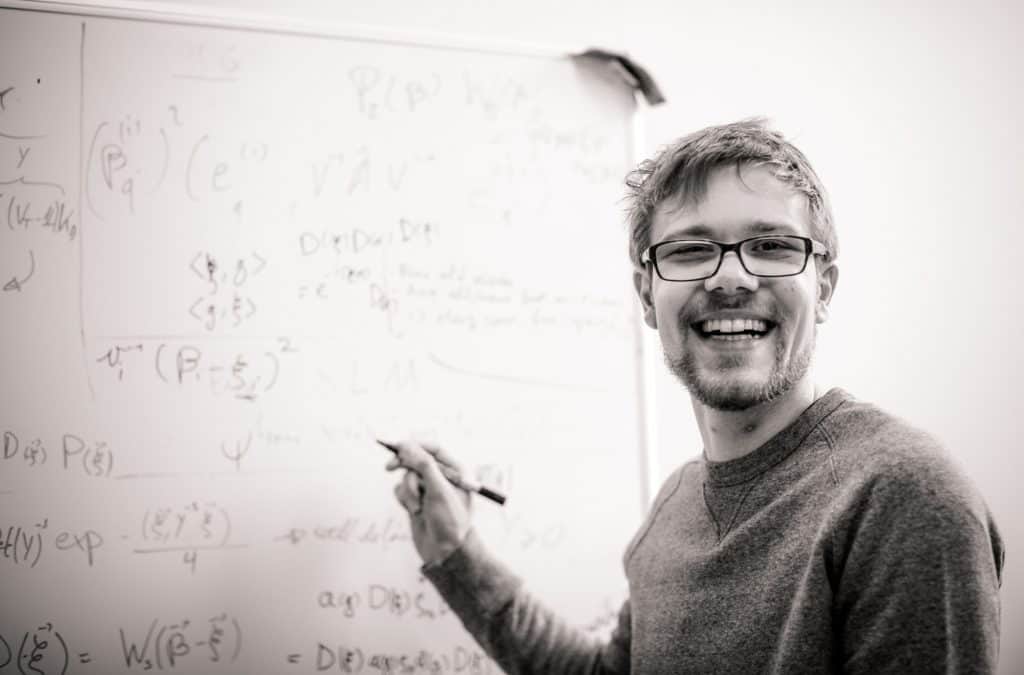

Mattia Walschaers: I lead the group’s theoretical activities, which means that my days are usually split between doing calculations on the blackboard, running simulations, and meetings with students, postdocs and other colleagues (many of whom are mainly working on experiments). On most days, the coffee machine is the most important piece of machinery I encounter. However, I regularly venture down the lab to check up on experimental progress, and at one point I even tried to learn to align some of the optics.

Ironically, the lockdown hit us exactly during the week when I was supposed to make one of my notorious ventures into the lab to help with tomography of a new type of photon detector. We often joke about things going wrong when a theorist goes down to the lab, but in this case, it really seems to have gotten out of hand.

Tiphaine Kouadou: I am an experimentalist, so my work revolves around my laboratory. Before the lockdown was announced, we were building a new experiment. My workdays included lab work and developing projects with our lab’s mechanical and electronic workshops.

The COVID-19 crisis forced us to stop all our experimental activities, so as a final-year PhD student I started writing my thesis instead. I had regular video meetings with my supervisors, during which we discussed my work and how we might resume our experiments once the lockdown’s terms and conditions were relaxed.

MW: We are based in Paris, and thus all of us went into a quite strict lockdown in the middle of March. On a personal level, this has been a harsh couple of months for many of us, because we have barely been allowed to go out on the streets. Some members of our group have been confined alone in an apartment measuring less than 20m2. Clearly, these conditions also put people’s mental health at risk, which is something we tried to be vigilant about.

Physics-wise, most of our theory work continues as usual. With paper, a pen, and a computer that has access to a computational grid, I can perform my own work in a normal way. However, supervising students has gotten more complicated now that we can no longer meet in person, and discussing theoretical physics without a shared blackboard is not always practical. We manage to get a lot of work done via video calls, where we discuss notes, papers, project proposals, and even future experiments. It’s a bit strange to spend most of your day talking to a screen, but we have somehow gotten used to it. We try to organize a coffee break over video call once a week, and we have a shared Mattermost (an open-source alternative to the Slack collaboration software) for the whole LKB.

Even so, I think we are all feeling the need for some face-to-face discussions, and now that (as of 11 May) the lockdown is officially over, we have regained a bit of freedom to circulate. It is clear that many people were longing for that.

A cautious return

TK: On 18 May, it became possible for us to restart experimental work. However, for the researchers allowed to work on-site, access to the university campus is restricted to a maximum of two or three days per week. Administrative services are limited, and mechanical and electronic workshops are closed, as is the IT department. This situation is supposed to run until the end of this month and we do not know what the plan will be for June.

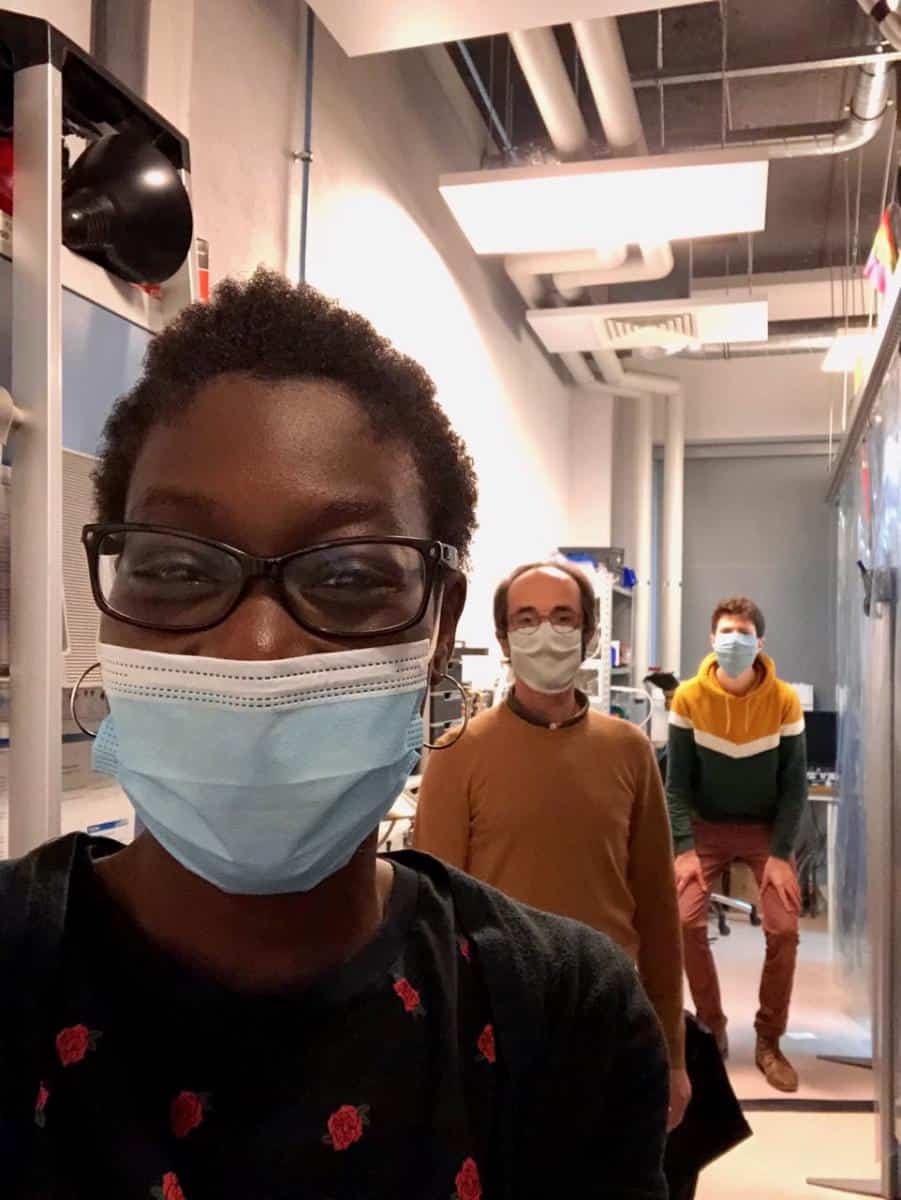

As our team is mainly composed of experimentalists, we are alternating the days when people come in to work, and also following new safety rules. For the moment, our main goal is to restart our experimental work safely and to limit contaminations via the experimental equipment. So, in addition to wearing masks, we placed a bottle of hand sanitizer at the lab entrance with the instruction that everyone should use it before touching the experiment.

MW: Across the university, roughly 15% of the normal research personnel have been allowed to return to their labs since 18 May. We hope that this percentage will be increased in June, but there are still a lot of unknowns. Getting everything organized has been a complicated exercise. We had to make choices about who was allowed to go back to the lab, and who has to continue working from home.

The university and the LKB direction committee have worked hard to instate a series of safety measures. At most, two people at a time are allowed in the same lab space or meeting room; disinfectant gel is available to everyone; everyone has to wear a mask at all times; and at lunch people are supposed to eat alone in their offices, or outside. There are even rules for going up and down staircases to uphold social distancing. We had long discussions about whether to recommend gloves while touching the optical elements in our labs, but we finally decided that it is more important to encourage people to wash their hands frequently. We are also planning to set up some sort of live-stream to allow people in the lab to communicate directly with those who are working from home.

There is a fine line to walk here, though, since several of the new requirements pose challenges for other safety regulations. After all, people should not be alone in the lab in case of accidents. Therefore, the LKB set up an ad-hoc system where people can use Mattermost to register their physical presence at the LKB facilities. They have to sign out when they leave, and they have to make sure that no one is left alone. Since the LKB includes many different research groups, with over 100 members in total, this system will clearly impose many communication challenges in the days and weeks to come.

Uncertain timeline

As for our theoretical activities, not much will change in the foreseeable future. I am actually interacting more with some of the experimentalists who are not allowed to return to the lab, since many of them have turned to doing some theory to keep making advances in their work. I am secretly hoping to convert them by introducing them to the joys of theoretical physics, but sadly I can see that they are longing to get back to their shiny lasers. I am also hoping to get back to having some blackboard discussions with my colleagues, but I am quite pessimistic about the timeline. I hope to be able to return at some point in July, but it is not unlikely that I will have to wait until the end of summer.

On a personal level, I am a bit worried about when I will be able to see my family again. I am Belgian, and as an EU citizen, the border between France and Belgium has never been a barrier before, but this changed drastically due to COVID-19. However, there is also a very clear silver lining, since I managed to go into lockdown together with my partner, who (for professional reasons) lives 700km away in Montpellier. We usually see each other only every two weeks, but the pandemic means that we have spent much more time together.

My biggest concern is the health and safety of the people around me, and I try to keep that in mind when the social distancing measures are starting to weigh. Professionally, I have managed to remain productive, and our group is still moving forward, so I am optimistic for the future. I think our habit of combining theory and experiments was an advantage for the lockdown. Our theoretical activities got a big boost during this time, which imposed some organizational challenges for me as a young permanent member of the group, but it was a good occasion to learn.