Jharkhand's daily-wage labourers left out of PDS safety net fear starvation as employment dries up during COVID-19 lockdown

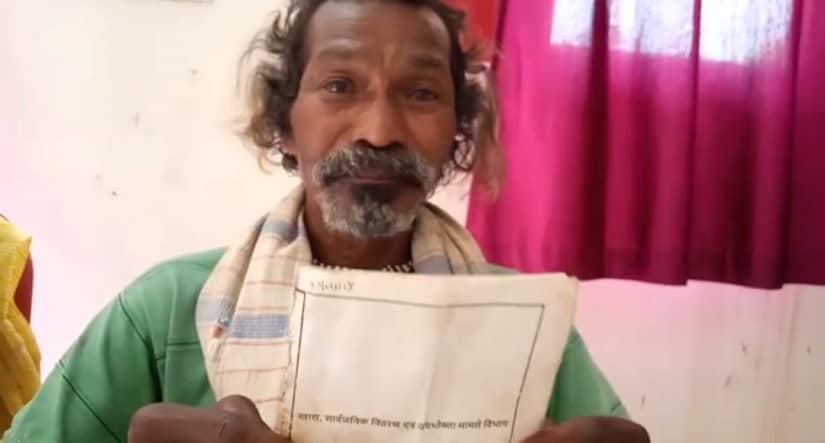

by Natasha TrivediJitendra Bhuiyan, a daily-wage worker in Jharkhand’s Palamu district, made one of multiple visits to the block office in Daltonganj (officially known as Medininagar) on 18 May, to submit his application for a red ration card.

With the red ‘PH’ card (priority household), he can get subsidised food grains every month for his six-member family. However, instead of the food security he is entitled to under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), Jitendra is stuck with a ‘saamanya’ or white ration card. With the white card one can only get subsidised kerosene and is meant for families above the poverty line.

The white ration card has become a bane for many daily-wage workers in many districts of Jharkhand, especially Palamu, Simdega, West Singhbhum, and Bokar. More so, since the nationwide lockdown over the coronavirus pandemic has left them without any income for more than two months.

According to the website of the Jharkhand government, 3,95,519 people are listed as white card holders in the four districts. This includes those who are above the poverty line, as well as, those who are below it. The white card is among the three issued by the Jharkhand government, and the others are:

- Red PH ration card – which gives the benefit of 5 kilograms of rice to each member in a BPL family per month at a subsidised rate;

- The yellow AAY (Antyodaya or ‘poorest of poor’) ration card – which allows one family to receive 35 kilograms of rice per month at a subsidised rate.

These are the two main types of ration cards listed under the NFSA’s Public Distribution System (PDS), and are uniform across all the states. State governments are also at the liberty to issue cards for socio-economic groups apart from the PH and AAY families.

Sukhru Topno from Simdega has been trying to get his white card cancelled. With his only son working in Punjab, the family is staring at weeks of no food in the absence of a ration card. Image procured by author

In Jharkhand, a state plagued by starvation deaths, several families eligible for the red or yellow cards have been issued white cards and are on the brink of hunger. A majority of such families live hand-to-mouth with only one earning member who is usually engaged in daily-wage labour, activists said.

Labourers worry their children will starve

The coronavirus lockdown, extended thrice since being imposed on 24 March, has exacerbated the challenges faced by labourers.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 36-year-old Agasti Dagarai was earning Rs 220 a day laying railway tracks in the Sonua block of the state’s West Singhbhum district. Dagaria works as a labourer with a private contractor in West Singhbhum district. Since the lockdown began, work has come to a standstill and there has been no income, he said.

Despite applying for a red card two years ago, he was issued a white card and is now deprived of the safety net of assured food grains. “When I received the white card, I went to the dealer to tell him that there had been a mistake. He asked for Rs 1,500 to get it fixed, but I didn’t have the money so I didn’t pursue the matter,” Dagarai said.

Dagarai also alleged that the dealer told him that the family will get money instead of food grains through the white card.

“We gave our documents to the dealer to help us apply for a ration card and when we got the white card, we went back to him to try to get it fixed. Then he said that we will get money, not rice. After that, we checked our account in the Sonua branch of SBI, but no money has been deposited so far,” he said.

“We have no daal, no vegetables, only 15 kilograms of rice is remaining now. We’ll eat that with salt and after that we will starve,” said Dagarai, “Now, without any income or ration, how will we provide for our children?” he asked repeatedly.

In regular circumstances, Dagarai spends an average of Rs 2,400 on food every month. This included 25 kilograms of rice, one kilogram of masoor daal, and vegetables. Now, the family has had to forego the pulses and vegetables.

In Simdega’s Kolebira block, Sukhru Topno (65) and his daughter-in-law Sushari travelled to social worker Taramani Sahu’s house to ask her for help in getting their white card cancelled.

Jitendra received the white ration card three years ago. “Since then, I have been running from one office to another, but no one has helped." Image procured by author

Topno’s son migrated to Punjab three months ago for work, but he hasn’t been able to send any money because of the lockdown. His son is the sole earner for the family of five.

Topno and Sushari, meanwhile, are attempting to make a living by selling the wood they collect from the forest. The family has also received 10 kilograms of rice from the mukhiya in April. However, since rice is their staple food, a “package of 10 kgs is not sufficient because it gets over in less than two weeks,” Sahu said.

She added, “They are in a desperate need of food grains and we have put forward the issue to the mukhiya several times, but he keeps skirting it. Sukhru used to do casual labour, but he is old and isn’t able to work at all anymore, so they have no support at the moment.”

Implementation of govt’s anti-hunger measures falls short

The measures taken by the Hemant Soren’s JMM government against starvation have been scattered and ad-hoc across the four districts. While some needy families have received food grains as part of the state government’s COVID-19-specific measures, others have been given rice by the panchayat mukhiya from the Rs 10,000 fund that has been stipulated for families in dire straits.

For instance, Dagarai said that he explained his predicament to an official from the block office who had visited the village over a month ago. He then received 25 kilograms of rice and was told that the government is providing only a “one-time” package of food grains.

Meanwhile, 30-year-old Prem Bhuiyan in the Daltonganj block of the Palamu district said that he had been given 10 kilograms of rice two weeks after lodging complaints with the dealer, the mukhiya, and various block officials.

“After complaining to many people, in two months I received one package of 10 kilograms of rice from the block office.”

30-year-old Prem Bhuiyan in the Daltonganj block of Palamu district said that he had been given 10 kilograms of rice two weeks after lodging complaints with the dealer, the mukhiya, and various block officials. Image procured by author

Prem, also a daily-wage labourer, received his white ration card four years ago, and has made several visits to the block office to get it rectified. “A year ago, when I again went with my request, an official asked me if ‘you have hands and legs, why can’t you work,” Prem said.

According to Prem, his father and two brothers as well, who work in brick kilns, have all been issued white cards. “My grandfather was a shepherd, none of us have a government job, we are a poor family. So why haven’t we been given proper ration cards?” he asked. With weekly earning of Rs 1,200, Prem said that the family is also getting by with help from their neighbours who are receiving ration.

“When I asked the mukhiya for help from the stipulated fund almost a month ago, he said it was spent. So, we asked our neighbours for 15 kilograms of rice, which lasted us less than a week, but we have to make do.”

In Bokaro’s Pichari district, Shanti Devi’s woes began even before the white card could arrive. “We applied for a ration card, but the operator in the block office told us that we have been given a white card. When we asked officials to correct it, they said that they can’t do anything because we’ve already been assigned the card,” she said..

Labourers face severe uncertainty over availability of work

Pre-lockdown, 30-year-old Jitendra Bhuiyan used to travel daily to the town centre of Daltonganj, around 11 kilometres from his village, with the hope of getting work on construction sites. On good days, he earned at least Rs 2,000 a week. But on days, he returned empty-handed.

“The availability of work is very uncertain. Usually, I join the crowd of labourers waiting to get assigned to a job, but some days there is absolutely no work,” he said.

Jitendra received the white ration card three years ago. “Since then, I have been running from one office to another, but no one has helped. There is no clarity on why I was given a white card or how do I cancel it and apply for another one.”

Incidentally, he had been waiting in the block office for over three hours with other white card holders when Firstpost spoke with him on 18 May. Jitendra said he cannot afford to give up till the issue is fixed this time, because the family is in dire straits without an income for more than two months.

Why is this happening?

James Herenj, convenor of the Jharkhand NREGA Watch said, “This loophole is occurring because there are no fixed eligibility criteria for white ration cards, like there are for red and yellow cards.”

He added that the government’s failure to update the population data since the 2011 Socio Economic and Caste Census (SECC) is also one of the main reasons, because in the nine years since the population in need of food security has grown.

“According to the 2011 SECC, 86 percent of the rural population was to be supported by the PDS. However, while the vulnerable population has increased, the government hasn’t expanded the cover beyond 86 percent. So, the spill-over population is being given white cards and being deprived of ration,” Herenj said.

Taramani Sahu, who is also a Right to Food Campaign associate, said there are major gaps in the way the government functions and the general public’s knowledge about how they function. “A majority of the families who’ve been given white cards are very poor, and their condition is worsening during the lockdown without any livelihood. They know that they have the wrong card, but they don't know where to get it fixed, which official to meet, what the protocol of cancellation and reapplication for a ration card is,” Sahu said. A lack of an active grievance redressal mechanism makes it even more difficult, activists added.

The Soren government announced extra ration entitlements for current red/yellow card holders and for those whose ration card applications were pending.

The Telegraph also reported, “…on 14 April the state government also included 8.4 lakh white card holders (who are not below the poverty line and would get only kerosene from ration shops) among beneficiaries who will get 10 kg of rice." However, Herenj said that no official notification was issued by the government to implement measures for white card holders.