Tafi Mhaka: Europe should pay reparations for colonising Africa

On 6 March 1957, Ghana became the first sub-Saharan country to gain independence from European colonisation. The liberation of African countries from would persevere and end with South Africa gaining independence in 1994.

by Tafi MhakaIn the last 63 years, Africa has made great strides in achieving political, economic and social independence. Despite facing great odds, independent African countries have endeavoured to develop new roads, schools, universities, clinics and hospitals and provide water and electricity, especially in historically underdeveloped rural areas.

They have tried, albeit with varying successes, to build democratic, multiracial states premised on equal opportunities for all. But as the coronavirus pandemic spreads around the world, the gradual progress experienced in Africa has become the subject of deliberate, intense scrutiny.

A tragic and familiar consequence of the pandemic engulfing the world is the determined analysis of Africa’s COVID-19 economic, health and humanitarian response as the result of profound African hopelessness.

Related Articles

Selmor joins Africa greats in concert

May 22, 2020 8,245

Tafi Mhaka: Zimbabweans are not the problem in South…

Apr 25, 2020 36,926

Tafi Mhaka: The MDC Alliance must take the fight to Zanu-PF

Apr 17, 2020 18,110

Tafi Mhaka: Amid COVID-19, South Africa is scrambling to…

Apr 12, 2020 16,402

Much has been made of “Africa’s fragile health systems” and the impact “underinvestment” and poverty will have on containing coronavirus in Africa, mostly in comparison to the abundant medical and monetary resources available in the West. The European Union, for example, has availed over €3 billion to support its members states.

African countries, meanwhile, have mostly struggled to finance shutdowns and subsidise businesses. Yet the old, morbid tales of mortal disasters unfolding in Africa have lacked sufficient context about the relationship between colonisation and Africa’s economic challenges.

In a study titled The Impact of Colonialism on African Economic Development, Joshua Dwayne Settles states that the demand for raw materials fuelled the establishment of colonies and created conditions that made it easier for Europe to deplete Africa’s resources.

Settles contends that “Colonialism was not just about economic subjugation, but about the ability to wrest control of the local economy from African rulers” and create states that are dependent on pursuing unequal trade with Europe.

So colonisation not only facilitated an extended, massive outflow of African resources and the wholesale appropriation of farmland, but it devastated local economies in Africa. Before colonialism disrupted their growth, African economies were integral parts of international trade.

Pre-colonial states such as Buganda, Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Asante thrived before colonisation set in. In West Africa, indigenous populations were producing commodities, like groundnuts and palm oil, for sale to European merchants.

And local organisations, such as the Fante Confederation in Ghana, established in 1868, sought to “develop and facilitate the working of the mineral and other resources of the country” and secure exports markets on fair, lucrative terms. Instead, because of colonialism, Africa reluctantly provided cheap raw materials and labour solely for Europe’s substantial industrial benefit for 75 years.

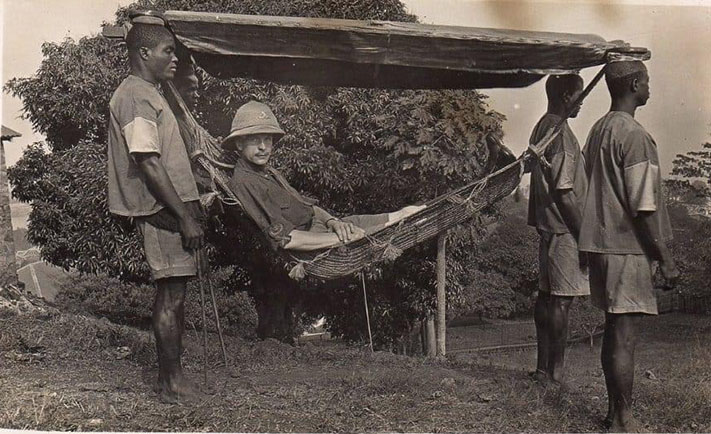

Through violent colonisation, European nations built critical infrastructure and men like Cecil John Rhodes emerged as enormously wealthy land barons, mining magnates and imperialist entrepreneurs, while Africans were relegated to oppressive poverty amid second-class citizenry.

Rhodes infamously said, “I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race.”

That perceived superiority inspired heinous colonial crimes and led to the establishment of “Rhodesia”. To Rhodes, conquering Africa appealed to his white supremacist leanings and he found meaning in illogical tropes that justified founding a perverse brand of extractive capitalism.

It facilitated the long and reckless extraction of petroleum, copper, chromium, platinum and gold for export to Europe, and enabled colonisers to monopolise land ownership. This while Britain, France and Germany built the political systems that aided economic plunder.

Hence, the case for reparations is strong and just: compensating Africa for decades of multifaceted colonial exploitation is both a moral and financial imperative.

Still, reparations can’t guarantee the return of valuable artefacts stolen from Africa, or undo generations of cultural and linguistic repression. Money can’t possibly compensate for the lives lost in the Maji Maji Rebellion, the San, Herero and Namaqua genocide and the Mau Mau massacre.

Plus, the trajectories African economies enjoyed in the pre-colonial era are forever irredeemable. So, no, reparations alone would not lead to an African renaissance, but they would, to a very limited extent, provide nominal, symbolic compensation for the incredible hardships endured and the countless natural resources shipped from Africa during colonialism. They would, however, help to establish a well-defined, unambiguous narrative about European repression in Africa.

They would be proof of an indelible recognition of the economic, social and political mayhem wrecked on budding African civilisations, and become an indisputable reference point for Africa’s largely mixed development.

To be sure, reparations would amply demonstrate that Africa is not just disadvantaged, as compared to Europe: it stands deprived by the enduring consequences of Europe’s colonial designs.