Guardian Sport Network

Harsha Bhogle on lockdown, the IPL and the future of cricket

The commentator speaks about Indian culture, his hopes for the women’s game and why he feels blessed every morning

by Jonathan DrennanBy Jonathan Drennan for the Guardian Sport Network

India has never been so quiet. Bustling streetside enterprises have closed; traffic has subdued; and the stumps have been pulled up on thousands of games of cricket. Harsha Bhogle has been commentating on the sport for nearly 40 years, but he cannot remember anything like this. “You can’t go out on to the streets anymore at all,” says Bhogle from his house in Mumbai. “When the National Party called a national ban, for instance, people used to still go out and play cricket. They can’t do that now. I don’t know what this lockdown will do to sport in this country, as sport is still seen as something that brings joy in India.

“I get so many people on my Twitter feed telling me how much they are missing live cricket. Every day on television here they are showing re-runs of every single Pakistan v India World Cup game. It is being shown ball by ball, not just the highlights. They are showing India v Pakistan World Cup games because, on Indian sports news, India never loses.”

Bhogle grew up in a home of academics in Hyderabad, where the large fields of the university became his own personal Eden Gardens. He played to a respectable club standard, but his ambitions in the game were always going to be fulfilled in the commentary box. He has come a long way since he first reported on the game as a teenager. Prior to lockdown, Bhogle was preparing for the start of the Indian Premier League, a competition he loves for its pageantry and entertainment as well as its world-class players.

“I’m missing cricket very much,” he says. “I’m missing being there watching the IPL particularly. I enjoy the IPL as it’s a very low-stress thing for me. You sit back and you can enjoy the game for three hours with the best players in the world. It’s not like an India v Australia Test series that consumes you completely. The IPL is a perfect tournament. It’s everyone’s soap opera. You tune in and are completely entertained.”

Since its first season in 2008, the IPL has proven wildly popular in India, attracting the world’s best players and paying them a fortune. Does Bhogle worry about the future of Test cricket in the modern, increasingly fast-paced India? “The most important man in Test cricket today is Virat Kohli, simply because he is going out and saying: ‘I want to play Test cricket.’ He is acting as a link between the Rahul Dravid and Sachin Tendulkar generation and the 12-year-olds in India today. Those 12-year-olds are only talking about Test cricket because of Virat Kohli. Otherwise, why would anyone want to play Test cricket in India, when it’s so much easier to play 20-overs cricket?

“In Indian culture, parents look after their children on the understanding that, as they get older, the children will look after them. That’s how our family structure works. That’s what happening in our cricket now. T20 is looking after Test cricket. It’s getting people into the game and showing them the joy of Test cricket, but I believe Test cricket is on very, very thin ice. Nobody has the time. It’s not that T20 is impacting Test cricket; it’s lifestyles – Netflix, WhatsApp and the internet, all the easy entertainment options that are available. Would someone want to watch a batsman playing and missing, and scoring 12 runs in an hour?”

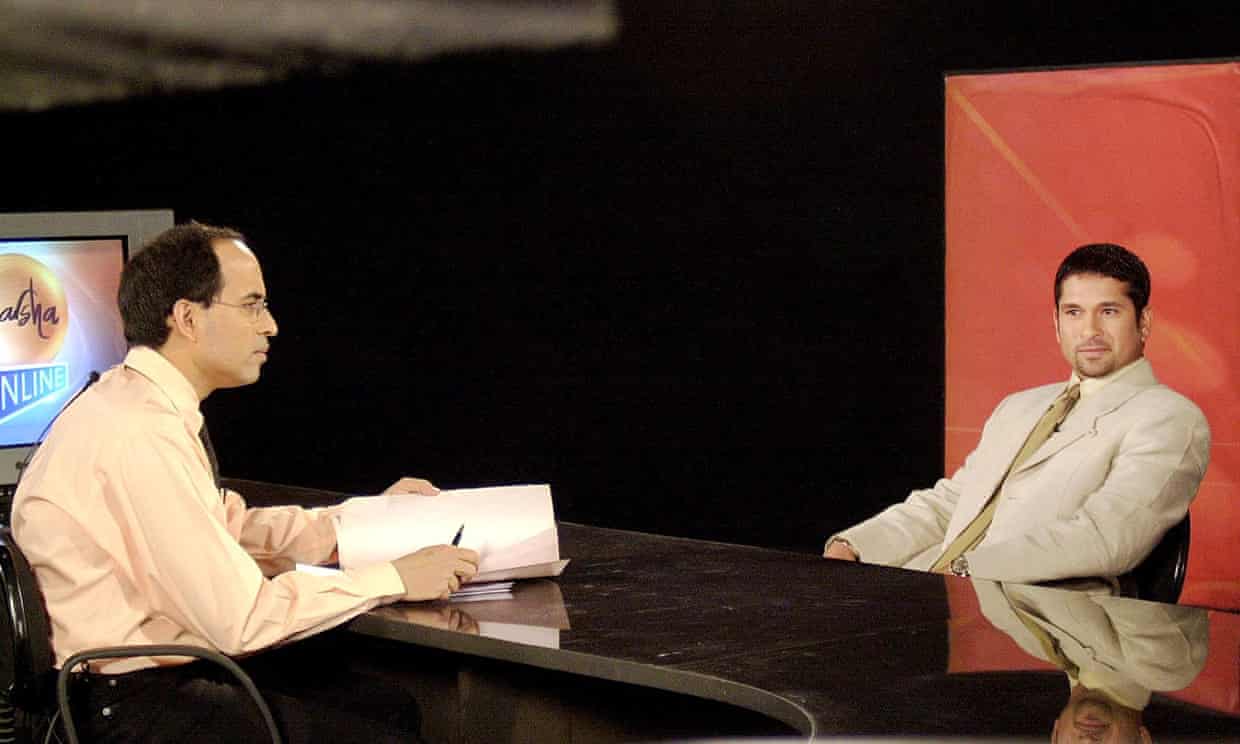

Although Indian society is developing rapidly, the idea of respecting your elders is slow to change. This can be a good thing and a bad thing, says Bhogle. “Even today, I have not heard Virat Kohli call Sachin, ‘Sachin’. He will call him ‘Paaji’, which means ‘elder brother’. It’s a term of respect. All the younger players coming through now always call Sachin ‘sir’. The coach is always ‘sir’’. He will never be called by his first name. In India, there’s still that respect for age and achievement that will always be around.

“Players like Sachin and Rahul knew that young players who were coming into the team wouldn’t come up to them, because they idolised them or had fear. They made a point to go up to the younger players and make them feel at home. A young player coming into the team is wide-eyed. He’s never going to go straight up to a Virat Kohli and say: ‘What do you think?’

“Part of team management is making youngsters feel at home in our culture. I am called ‘sir’ by young scorers in our commentary box and I have to tell them to stop and please don’t betray my age. I believe that respect will never go away in our culture.”

One thing that is changing in India is the development of women’s cricket. Earlier this year, a crowd of 86,174 people watched India play Australia in the Women’s T20 World Cup final at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. “Getting to the final of the T20 tournament has done wonders for the women’s game in India,” says Bhogle. “If they had won it, the game would have really taken off for women.”

What next for the women’s game? “There’s a lot of talk about a women’s IPL and I am almost certain we are no more than two years off a women’s IPL. I don’t know how much money will be in it, given that a lot of our players come from small towns, and given the orthodoxy, but it will come through eventually.

“Women’s cricket will do well because of the broad acceptance of cricket in India and the possibility that these players can earn good money. We’ve always had good women athletes in this country. The base of numbers might be small, but the standard has always been very good.

“Interestingly, our number three sports earner is a female badminton player – there’s Kohli, Dhoni and then [PV] Sindhu. Sindhu earns a lot more money than a lot of cricketers now because she won a world title. She won silver in the Rio Olympics. That Olympic badminton final is one of the most viewed television events in India. The country stopped and everyone was watching Sindhu play. It shows that as a country, we absolutely can get behind female sport.”

When Bhogle began his career, he completed match reports on an old manual typewriter in the baking sun at small regional cricket grounds. He now embraces digital media completely, with his video blogs often getting millions of views alongside his televised commentaries. He has more than eight million followers on Twitter and can find himself mobbed at stadiums in India. “There must be a higher force up there, because I very often believe I didn’t deserve the life I got. I wake up every morning thinking I’m blessed. I really hope I haven’t taken all of the family luck with me. The life I have had is as blessed as you can be.”

The streets, stadiums and fields remain empty, but cricket will return. Bhogle is counting the days.

Jonathan Drennan is on Twitter and you can read his interviews here.