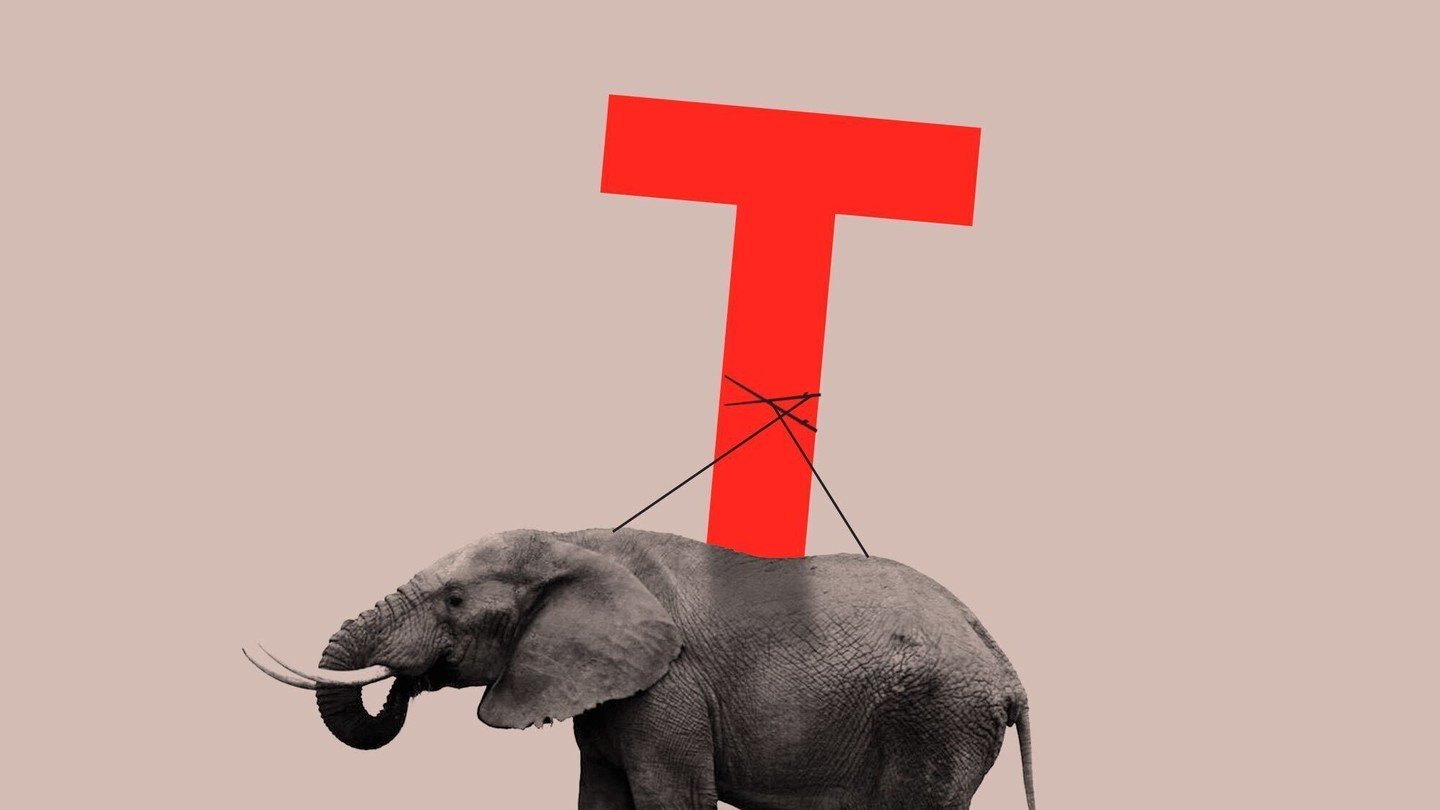

The Price of Trump Loyalty

by Todd S. PurdumUpdated at 4:19 p.m. ET on May 25, 2020.

In the future museum of Never Trumpers turned Ever Trumpers, Senator Cory Gardner of Colorado will have pride of place. In 2016, Gardner called Donald Trump a “buffoon,” left the Republican National Convention after one day rather than watching him formally receive the party’s nomination, called for him to drop out of the race after the release of the Access Hollywood tape, and said he would write in Mike Pence’s name on his presidential ballot.

Now Gardner, perhaps the Senate’s most endangered Republican incumbent, is locked in an uphill battle for reelection in a state trending bluer by the day. He trails his probable Democratic opponent, the former governor and erstwhile presidential candidate John Hickenloooper, by double digits in the polls. In a sharp about-face, Gardner has backed Trump at every turn since endorsing the president for reelection last year.

“He’s been with us 100 percent,” Trump said of Gardner at a February rally in Colorado Springs, at which Gardner lavished praise on the president.

What happened?

Not so long ago, there was a time in American politics when elected officials who found their state’s voters shifting beneath them would adjust their partisan loyalties to stay in power. Former Senators James Jeffords of Vermont and Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania both left the Republican Party when its national agenda grew out of step with that of their voters. A generation of southern politicians, from George Wallace to Strom Thurmond, adapted its stances on race as black voters’ access to the ballot box rose.

“I think I can understand something of the pain black people have come to endure,” Wallace told a black church audience in 1979. “I know I contributed to that pain and I can only ask your forgiveness.” Thurmond, who ran a segregationist campaign for president in 1948, never apologized for his past views, but he reliably delivered federal aid and programs for black constituents, and in 1970 became the first southern senator to hire a black staff aide and sponsor a black candidate for a federal judgeship.

These days, Trump’s hold on the GOP base is so total that Republican incumbents around the country cross him at their peril. Tribal loyalty is the new normal. In Gardner’s case, cold numbers make the point. At the beginning of Trump’s term, Gardner was willing to take an independent tack. He pressed in vain for creation of a special committee on cybersecurity, in part to investigate Russian hacking of the 2016 election. He supported a bipartisan immigration-reform bill written by John McCain that his fellow Republicans soundly defeated. The Lugar Center, an independent nonprofit in Washington, D.C., that promotes cross-party cooperation, named him the fifth-most-bipartisan senator in the 115th Congress, which ended in 2018. But those stances hurt him with Republicans back home.

By January 2019, after Gardner broke with Trump and voted to end a 34-day government shutdown without providing financing for the president’s border wall, Trump’s favorable-unfavorable rating among Colorado Republicans was 84 percent to 15 percent, while Gardner’s was a comparatively weak 59 percent to 26 percent, according to the KOM Colorado poll.

In the most recent KOM survey, Trump’s favorability rating among Republicans dropped slightly, to 78–21, while Gardner’s rose, to 72–19. But that increase is not nearly enough to compensate for Gardner’s abysmal favorability rating among undeclared voters, now the largest slice of the Colorado electorate. Among those voters, Gardner scored just a 29 percent favorable rating, compared with 62 percent unfavorable.

So sticking with Trump may be the best available strategy for Gardner, even if it’s not sufficient to win in a general election in a state where Trump lost to Hillary Clinton by just less than five percentage points, and where Democrats won every statewide office in 2018. (Gardner’s office did not return requests for comment for this article.)

“I’m not sure there’s a better path for him at this moment,” says Curtis Hubbard, a partner at the Democratic consulting firm OnSight Public Affairs, part of the consortium that conducts the KOM poll. “Part of the calculation for the GOP nationwide is, they understand that there isn’t any path forward that doesn’t include kissing the ring. And it’s unfortunate, and it probably will result in Gardner’s being a one-term senator. I say it’s unfortunate for him because I think he’s a better Republican than he’s letting on.”

After two terms in the House, Gardner won his Senate seat in 2014 by just 1.9 percentage points against the Democratic incumbent Mark Udall. He campaigned as a freethinker and relative moderate on issues such as immigration, supporting a move to give undocumented immigrants serving in the military a path to citizenship. Once in office, he continued to walk a sometimes maverick path. He worked with his fellow Coloradan, Democratic Senator Michael Bennet, on a bipartisan immigration measure. And he has opposed the Trump administration’s anti-marijuana policies, collaborating instead with Senator Elizabeth Warren to allow cannabis businesses to use the banking system in states such as Colorado, where pot is legal.

In 2016, he took on the chairmanship of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, the party’s campaign and fundraising arm, and his efforts there helped defeat red-state incumbent Democratic senators, including Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota and Joe Donnelly of Indiana, in 2018. That kind of credential might once have been rewarded as a sign of party loyalty, but seems to mean less among Colorado’s increasingly conservative GOP electorate, a leading Republican pollster there explained to me.

“To be honest, he had a very high profile running the senatorial committee, but he also always tried to come across as a senator for all Coloradans, which is really the kind of image you want to project to voters,” said the pollster, David Flaherty of Magellan Strategies, in Louisville, Colorado. “But Donald Trump has completely blown up that strategy. He’s more popular in Colorado than George W. Bush was in the winter of 2001 after 9/11. The bottom line is that in our state, he has to run with President Trump, win or lose. Events beyond Cory’s control have affected the realities here.”

Gardner is far from the sole Republican forced to toe the Trump line or pay the price. Senators Martha McSally in Arizona and Thom Tillis in North Carolina are hewing to a similar strategy even in the face of strong Democratic opposition in states trending purple. Former Senators Bob Corker of Tennessee and Jeff Flake of Arizona, both of whom were sometimes outspoken critics of Trump, retired rather than facing probable defeat from more conservative primary challengers in 2018. Former Senator Dean Heller of Nevada mostly supported Trump, but it still cost him, two ways: In 2018, he became the sole Senate Republican to lose a reelection race, to his Democratic challenger, Jacky Rosen. At the same time, Heller’s brief flirtation with opposing Trump’s proposed repeal of the Affordable Care Act was enough to cost him a hoped-for seat in the president’s Cabinet.

“The party is now more a cult than a party,” says Norman Ornstein, a veteran congressional scholar at the American Enterprise institute and an Atlantic contributor. “The imperative not to be shunned or excommunicated is overwhelming—and it’s not just fear of Trump or Fox News. All their friends would treat them like apostates too.” GOP incumbents face a pragmatic choice, Ornstein told me: lose their base or risk losing swing voters. “They have all decided to double down on the base, and in Colorado that is an especially problematic choice, given the sizable number of suburban, college-educated voters repelled by Trump.”

Hickenlooper, who is the front-runner for the Democratic nomination against Andrew Romanoff, former speaker of the Colorado House of Representatives in next month’s primary, says Gardner has forsaken the platform he ran on six years ago.

“Senator Gardner promised to be an independent voice, but he's caved to Trump and corporate special interests,” Hickenlooper said in an emailed statement. “Together they've tried to yank away Coloradans' access to health care and rolled back protections for our clean air and water. Coloradans are fed up and want someone in Washington who will fight for them.”

Indeed, Craig Hughes, a prominent Democratic consultant in Colorado, who helped pilot Bennet’s reelection in 2010, expressed puzzlement at Gardner’s approach. He had been among the most closely watched senators during Trump’s impeachment trial in January. He was among the handful of Republicans who successfully pushed Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to allow extended time for both sides to make their case, but he then ultimately voted against calling witnesses or convicting the president.

“It’s baffling,” Hughes told me. “I don’t know how he wins at this point. He’s the only Republican elected statewide now as it is. It has huge implications. Colorado is a state that for decades has rewarded bipartisan and independent leadership, whether that’s the pragmatic streak of a Michael Bennet or the independent streak of a Gary Hart. I’m convinced that a politician as talented as Gardner could have dared a different path here. There was a way to navigate and be seen as loyal without completely abasing yourself to Donald Trump and everything he does.”

But at least one recent casualty of Gardner’s political skill is not so sure about that. “For him to pivot now would probably alienate a lot of the people he’s counting on to turn out to vote,” Heitkamp told me. “And it would look pretty hypocritical to everyone else in the state, so better to justify his decision. I don’t think he has a choice. If he were going to pivot away from the president, he had to do it long ago.”

Heitkamp represented a state where former Democratic Senators Byron Dorgan and Kent Conrad won reelection with 60 percent of the vote, even though the state has been reliably Republican in presidential politics since 1968. Even 10 years ago, Heitkamp said her pollster explained to her, some 20 percent of Republicans nationally were willing to split their vote; now that number is less than 5 percent.

“I never imagined that Cory Gardner was going to tack to the left,” Heitkamp said. “He’s counting on a very energized Trump base. Or he’s counting on being secretary of the interior in a second Trump term.”