Sounding It Out

Teaching my daughter to read in self-isolation

by Ryu Spaeth

When my daughter began homeschooling earlier this year—a string of words that, even now, causes me to rub my eyes with disbelief—I went through something like the stages of grief, landing at acceptance only after a protracted battle with denial. How could I juggle a full-time job while teaching a five-year-old the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic? It seemed impossible, absurd, like asking me to be in two places at once.

Yet the defining characteristic of the coronavirus crisis is how quickly the absurd can overtake reality. My wife and I now alternate on homeschooling duties, and a typical morning goes like this: I wake up early, make my daughter breakfast, and sprint through the assignments that are listed in Google Classroom. A couple writing tasks, some drawing, a few math exercises, a science video—done. Scan the pages of her gangly script onto my iPhone, AirDrop them into the iMac, upload to the cloud, throw the pages into the trash. Then I log on for work, and she spends the rest of the morning bathed in the blissful glow of uninterrupted screen time. Every so often she participates in a Google Hangout with her classmates, a madhouse of 20 kids trapped in tiny boxes blabbing to everyone and no one at the same time.

Is it the finest education taxpayer money can buy? No. Do we sometimes pretend to complete assignments we can’t be bothered to do? Yes. (Try doing “gym” in a Brooklyn apartment.) Is it the logistical nightmare I feared? She is only in kindergarten, after all, spared the deluge of worksheets that have inundated the lives of older children and their families. Homeschooling has become a chore, distinct from other chores in that it occasionally reminds me how much I have forgotten of my own education. (It amazes me that there was once a time when I knew what a rhombus looked like.)

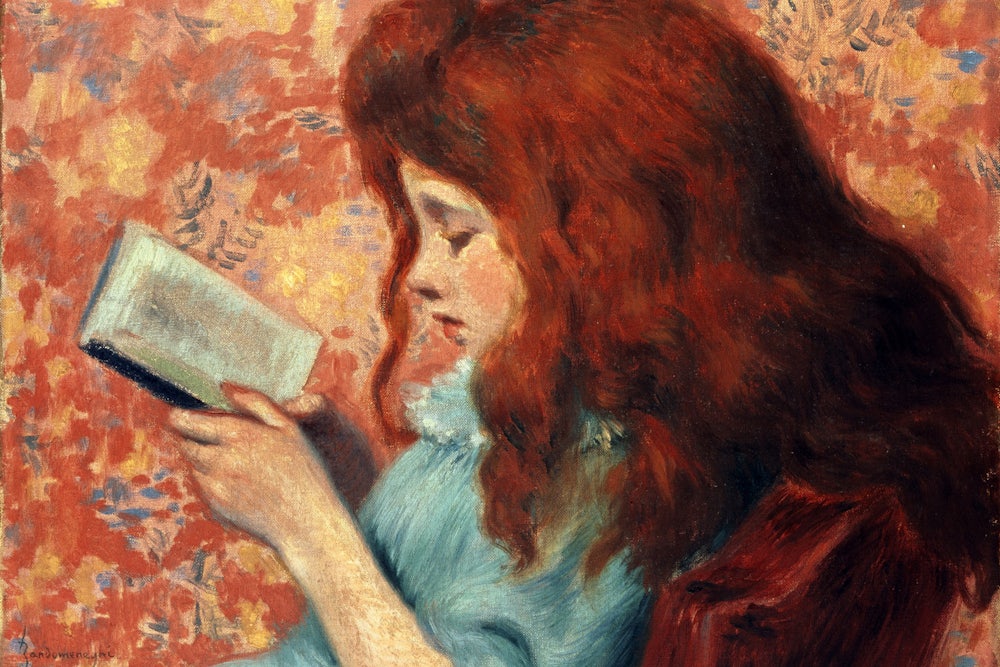

There is one aspect of her quarantine education, however, that does interest me—that has, in fact, become something of a fascination. It is the 20 to 30 minutes set aside each day to teach her how to read.

There are things parents are expected to teach their children: how to ride a bike, how to catch a ball, how to be a decent person. But there are other things that are learned in school, and with good reason. Teaching a child to read is hard.

It obviously doesn’t help that I have no idea what I’m doing, falling back on some trusty all-purpose tools: encouragements and threats, bribery and blackmail. It is not at all like teaching her how to speak, which involved almost no active participation on my part, since children largely learn to speak through osmosis, absorbing the rudiments of language as if they drift about in the air. (Which, in a sense, they do, in that the sounds of speech are all around them.) Reading is different. Reading requires focus, ambition, and a lot of work.

When my daughter and I first began this regimen, curling up on the couch with a book, it was an inversion of our usual routine: She would be reading the book to me. There were other inversions, too: This normally loquacious child was having trouble with her words. They came out slowly, haltingly, sometimes not at all. The finger tracing the page would hover for a ponderous moment over what was, apparently, a senseless jumble of letters. Sometimes, frustrated, she would have to reset her brain to proceed: “OK,” she’d sigh, then vigorously shake her head clean of its confusion like an Etch A Sketch.

You can hardly blame her. From a student’s point of view, the English language makes no real sense. She has been taught that English is a phonetic language, that certain letters laid out in certain combinations make certain sounds, but the truth is that there are so many exceptions and quirks that the so-called rules are useless half the time. There are words she can read by sounding the letters out: his, tree, eggs, bunny. There are others that seem to only get more obscure the longer she strains to unlock their meaning, and often these words are the most common, their idiosyncrasy enduring through sheer use. Nothing she has been taught can prepare her for a word like would. Even a small word like said is tricky. (She doesn’t understand why it rhymes with dead—and by all rights, it shouldn’t.) The word ocean—so lovely to look at, so strangely evocative of the thing it represents—is a phonetic catastrophe, the c suddenly switching to the “sh” sound, the ea inexplicably approximating a u.

Much of English is basically ideographic, requiring readers to simply memorize the sound of an otherwise incomprehensible collection of dots and loops and strokes. Which means that mastering the ability to read, like so much else in life, requires practice and repetition—not exactly the favorite activities of young children. When facing a particularly daunting block of text, she will wriggle out from the nest I have made of my arm and lie stretched out on the couch, eyes closed tight. Teaching her to read is less about helping her with the more difficult words and explaining how particular arrangements of letters are pronounced, than about urging her to sit up, to concentrate, to put her shoulder to the wheel. The reward for crossing the balance beam of a sentence, wavering all the while, is the affirmation she seeks when she dismounts and turns her shining face to mine: Good. Excellent. Perfect.

The other reward is progress—genuine, palpable progress, in just a few short weeks. There is no rushing this kind of work, it can only come with time, and time has a way of working its magic. As we both sit there staring at the page, the whole world seems to slow down, to stand poised over a sentence, a word. Every syllable is hard-won, but then a mental dam breaks and the word plops out: night, forest, mother. With each passing day the words come faster and faster, and she laughs with delight as the meaning of them dawns over her mind.

There are setbacks, of course, days when she seems to forget the simplest words and I lose my patience. We have better luck with classic children’s books, the ones I used to read to her in her infancy: The Runaway Bunny, Green Eggs and Ham, Where the Wild Things Are. There is a rhythm to good writing that eases the passage from page to tongue, that makes reading more intuitive and natural. (All parents learn a lesson about good writing by reading aloud: Charlotte’s Web, for example, rolls beautifully in the mouth; Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, not so much.) So she reads back the sentences I once read to her: and an ocean tumbled by with a private boat for Max and he sailed off through night and day; “If you become a bird and fly away from me,” said his mother, “I will be a tree that you come home to.”

The ultimate triumph is when it all clicks, when the words become something more than sounds, something more than schoolwork—when they become vessels for thought and feeling. “It’s so sad,” she said after we completed The Giving Tree. “The boy destroys the thing he loves the most.”

What is it about these humble milestones that give me such happiness? In her otherwise stoic memoir about dying from cancer, Jenny Diski laments that her grandchildren will get old without her: “Oh, I am so sad not to be seeing more of their growing up.” I think about that enigmatic line a lot, how odd it is that the great joy of having a child is simply watching her grow up, even when she is just learning what I have already learned and experiencing what I have experienced. Today it is learning to read; tomorrow it will be riding a bike without training wheels; and one day, perhaps, it will be having a child of her own. What I think Diski was saying is that it’s a wonder to behold those experiences afresh, through the eyes of a beloved; that these experiences are, though we may have forgotten, wondrous in themselves.