How identity-driven conflicts fuel Ethiopia's incendiary social media rhetoric

An army of social media personalities stoke inflammatory content

by Endalkachew ChalaHeads of states from several eastern African countries gathered in October 2019 in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, to celebrate the grand opening of Unity Park, an urban park located within the imperial palace.

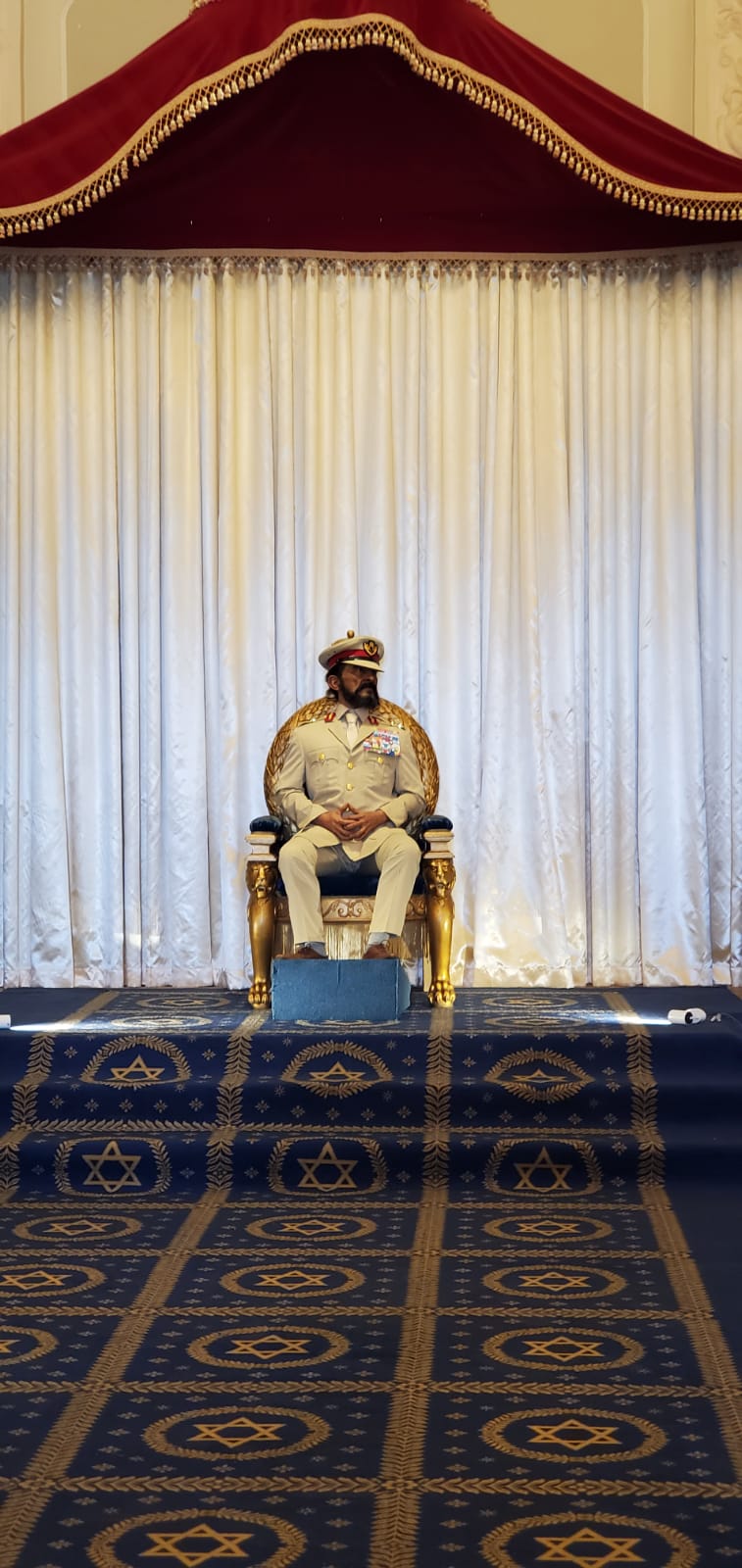

The park — the personal initiative of Ethiopia’s reformist Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed — contains Ethiopia’s historical, ethnic and culture galleries. It also maintains a display of a colossal wax statue of Ethiopia’s past rulers including Emperor Menelik II and Emperor Haile Selassie — two monarchs whose combined reigns lasted about 70 years.

The park aims to tell the story of all Ethiopians and celebrate the country’s diverse ethnicities, religions, cultures, historical figures, and endemic plants and animals.

But a quick scroll through the news about the park’s opening on social media revealed politicized, nationalistic reactions with two mutually exclusive narratives that fell largely along ethnic lines of the two major ethnolinguistic groups: Amhara and Oromo.

At the core of this divide is two mirror-opposite reactions to the unveiling of the monuments that depict two emperors sitting on their thrones — adorned with imperial regalia: They represent entrenched fault lines in Ethiopian politics.

Amhara nationalists were largely pleased even though some slammed it, describing it as Abiy’s vanity project — Abiy himself identifies as Oromo.

Meanwhile, several Oromo politicians and campaigners were furious — particularly, prominent opposition politician Jawar Mohammed, who was irked. Jawar said that building wax statues for Emperor Menelik II and Emperor Haile Selassie is an affront to Oromos and to all other ethnic groups crushed by the emperors.

Emperor Menelik II is widely regarded as the first modern Ethiopian monarch who transformed the Ethiopian State. He is venerated as a symbol of freedom and forgiveness; he is also blamed for kicking people in southern Ethiopia off their land and privileging Amharic language and Christianity.

The next day, Jawar along with Lencho Leta, a veteran politician and a founding member of Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) led a pilgrimage to the east-central district of Hetosa of Oromia, Ethiopia’s largest region, to visit the Anole Martyrs memorial monument, the historical site that signifies an enduring grievance of Oromo nationalists over what they call Emperor Menelik’s II brutal killings, cultural marginalization and loss of their ancestral land in the late 19th century.

Weeks later in a television interview, Jawar said:

As long as they elevate Menelik, we will dig out his crimes and make generations know about his crimes, as long as they elevate Haile Selassie. … we are going to do that.

This was not a one-off case.

After Abiy lifted the oppressive lid off the nation in April 2018 — ending 27 years of dictatorship — controversies about cultural events, flags, political rallies, monuments and the significance of past rulers began to take up the bulk of Ethiopia’s social media conversations — which were often laced with inflammatory language.

It is a recurring pattern.

Briefly, it runs like this: A government official, opposition leader, journalist or prominent celebrity opines about a historical figure’s significance, let’s say, Emperor Menelik II, on one of the popular social media platforms. Within minutes, social media platforms are swarmed by hundreds of supportive or scathing responses.

These culturally-charged exchanges reinforce an atmosphere of resentment across numerous online spaces among different Ethiopian ethnic groups — or more accurately, their elites. These jabs entrench the feeling that one’s ethnic group is threatened with extinction as the object of another’s aggression.

Multiple TV stations that sprouted after April 2018 as a major part of Ethiopia’s fast-changing media landscape have tended to echo and amplify this division — with fatal consequences.

For example, communal violence rocked Oromia after Jawar wrote on his Facebook page alleging that government authorities had plotted to assassinate him in October 2019. The regional coup plot in the Amhara region in June 2019 can also nominally be connected to ultra-nationalist social media narratives.

In many cases, an army of Facebook and YouTube personalities, government supporters, opposition figures, political parties and diaspora journalists often participate in or seed inflammatory information into an already complex, confusing and heightened social media ecosystem — often as a way of gaining support for their causes.

How two opposition figures stoke support

Two opposition figures, Jawar Mohammed, member of Oromo Federalist Congress and Eskinder Nega, a former political prisoner and a chair of a recently formed political party, Balderas for Genuine Democracy, are spokesmen who stand out for the way they use social media to garner support.

Jawar, with nearly 1.9 million Facebook followers — often enthusiastic supporters — positions himself as a defender of Oromo interests. With a massive following, he commands symbolic importance to the Oromo youth movement known as Qeerroo and is generally portrayed as their leader.

Eskinder, on the other hand, has become increasingly reliant on Twitter as a means of bolstering support. Although Eskinder was late to join Twitter, he developed a sizable following and his comments often provoke furious reactions from detractors. His embrace of the platform is seen as a political imperative as mobile devices and mobile connectivity have become more widespread.

Eskinder routinely uses his Twitter handle to accuse Qeerroo members of committing genocide against religious and ethnic minorities in Oromia. His framing of Qeerroo resonates with thousands of Twitter accounts that represent Amhara nationalists and Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church followers.

Although Jawar and Eskinder dominate two different platforms — Facebook and Twitter — their negative chemistry is equally apparent.

Both manage to articulate sharply opposing views on issues like Ethiopian federal structure, the legal status of Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa, an enclaved multi-ethnic city within the border of Oromia, the history of Emperor Menelik II and the Ethiopian constitution.

They aim to strengthen their already solid connections with their followers on social media. The reactions, comments, retweets and shares on Facebook and Twitter are higher than any other opposition figures.

And for all the differences between Eskinder and Jawar, they both do their fair share of injecting misleading information into Ethiopia's information ecosystem.

Often, Eskinder spins and overblows Ethiopian exceptionalism, destruction of historical sites and emphasizes atrocities committed in the Oromia region.

For instance, in the following tweet, Eskinder wrote approvingly that Amharic was selected to be included among the working languages of the African Union. But Amharic was never selected:

Since September 2018, the two have been locked in a long-running battle that played out most recently in November 2019 in the United States, when both toured to raise funds from members of Ethiopian diaspora groups for their political projects in Ethiopia.

No moment better captured the rivalry and the ideological contestation between the two men than their tour in the United States as their supporters played a game of cat-and-mouse throughout their tours.

Jawar’s tour had come on the heels of several tumultuous days in which communal violence spread across Oromia, which led to the death of 86 people after his allegation on Facebook sparked off a chain of reactions that started with his supporters gathering in front of his residence in Addis Ababa.

His detractors say his Facebook post caused the death of 86 people — and Eskinder, in particular, pinned the responsibility on him.

Jawar denied that his posts had anything to do with the violence, claiming instead that his actions actually prevented worse violence.

As he traveled across the United States, his supporters showed solidarity, coordinating town hall meetings and raising funds in various US cities with sizable Oromo populations.

People opposing Jawar, — most of whom are members of Eskinder’s support base — held a series of rallies opposing Jawar’s town hall meetings.

Like Eskinder, Jawar also has a habit of using questionable persuasion techniques. He often accuses authorities of the Amhara regional state of being nostalgic for Ethiopia’s imperial era and highlights violence that targets minorities in the Amhara region.

After he completed his US tour, Jawar accused authorities of Amhara regional state of organizing and funding what he described as a “hateful, shameful and violent campaign.”

As proof of his accusation, he accompanied his note with a photograph that showed a top-level Amhara regional state official, Yohannes Buayalew, posing with Yoni Magna, a diaspora-based social media personality who is notorious for his rants, insults and conspiracy theories.

The attempt is to insinuate that Amhara regional state officials have worked with Yoni Magna, — who was also seen at one of the demonstrations.

Some people did openly hurl bigoted slurs used to refer to an individual of Oromo ancestry during the protests, but there is no evidence to suggest that these rallies were in fact organized and funded by Ethiopian authorities.

Ultra-nationalist sentiment through songs

Until now, inflammatory language has been confined to writing, memes, short clips, graphics and pictures. But as the role of social media gains ground, the terrain of ethnic tension has expanded to YouTube music videos.

A new law on hate speech and disinformation

Earlier this year, Ethiopian lawmakers approved the Hate Speech and Disinformation Prevention and Suppression Proclamation, to curb the spread of hate speech and disinformation to promote “social harmony” and “national unity.” Rights groups, however, say the law is dangerous for freedom of expression because it contains broad and vague definitions, and provisions that do not align with international human rights standards.

In a flood of Afan Oromo and Amharic language music videos, singers promote nationalistic narratives that assert the superiority of their group — sometimes even promoting conflict with the other group.

Some of the most nationalistic expressions in songs focus on the homeland, flag and historical figures. Praising Emperor Menelik II as a liberator or denouncing him as a monster has long been a recurring theme.

In fact, there is a Facebook page that went up in 2013 to highlight the atrocities committed by a soldier of Emperor Menelik II.

But the launch of Unity Park elicited several Oromo music videos that focus on ethnic origins of government authorities.

Because the park is Abiy’s project, some songs portray him as a person who committed ethnic treason by honoring Emperor Menelik II. One song depicted him as a sellout; another one questions if he is an Oromo at all.

Caalaa Daggafaa, an Afan Oromo singer, accused Abiy of being a sellout for praising past monarchs. He rails against the statue of Menelik II, whom he described as a monster.

In the same video, he pays respect for the armed forces of the Oromo Liberation Front, describing them as heroes doing a tough job by continuing the struggle for the emancipation of the Oromo people.

Meanwhile, Amharic singers deliver odes to Menelik II, describing him as a unifier and liberator.

In one music video, Dagne Walle, a rising Amharic singer, swings toward the camera, wielding his rifle while humming that he has inherited valor from Menelik II — alluding to the emperor as his father.

Footage of crowds with traditional cloth armed with rifles, stomping their feet while waving Ethiopian flags, and a roaring lion punctuates the music video, titled “Wey Finkich” (“Hell No”).

These songs rack up a huge number of views on YouTube — reaping advertising dollars while hardening ethnic polarization.

This article is part of a series called “The identity matrix: platform regulation of online threats to expression in Africa.” These posts interrogate identity-driven online hate speech or discrimination based on language or geographic origin, misinformation and harassment (particularly against female activists and journalists) prevalent in digital spaces of seven African countries: Algeria, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Sudan, Tunisia and Uganda. The project is funded by the Africa Digital Rights Fund of The Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA).