The music essay

From Germany to Detroit and back: how Kraftwerk forged an industrial exchange

Kraftwerk’s robotic rhythms resonated loudest in deindustrialising 1970s Detroit and gave rise to techno – starting a cultural feedback loop that continues today

by Marcus BarnesWhen the death of Kraftwerk co-founder Florian Schneider was announced last week, the loudest tributes came from the electronic music community. Kraftwerk’s pioneering approach, using synthesisers and sequenced drum arrangements to evoke robotic or industrial rhythms, became the blueprint for Detroit musicians such as Juan Atkins, who coined the term “techno”. Forty years later, an array of electronic genres have been created from that blueprint: Schneider and Kraftwerk created a feedback loop between Germany and Detroit that has existed for more than half a century.

When Schneider and Ralf Hütter started Kraftwerk in 1970, their influences included several Detroit-based acts including the Stooges, MC5 and, according to later member Karl Bartos, Berry Gordy’s Motown label. Gordy initially worked for the Ford motor plant, and gave Motown an industrialised music production-line inspired by Detroit’s automotive industry. This was the ice-breaker in the conversation between his city and Germany – Kraftwerk’s automated drums, vocoder refrains and future-facing outlook also stemmed from the conveyor belts, piston-driven machinery and monotonous rhythm of factory life. This inescapable repetition of sound and movement – programmed, precise – was present in Detroit and Dusseldorf, both industrial centres.

Released in 1974, Autobahn provided Kraftwerk’s international breakthrough, setting the wheels in motion for their first tour of the US in 1975. It was a moderate success, but if it hadn’t been for radio and club play – and the record shops that supplied those DJs – then Kraftwerk would not have had the impact they did. Downtown Records in New York was one of many spots where Afrika Bambaataa would pick up the records he played in his legendary freeform sets at block parties in the Bronx. Known for its eclectic stock, Downtown (and other similarly idiosyncratic outlets) helped deliver Kraftwerk’s avant-garde sounds to America’s black communities. On the radio in NYC, Frankie Crocker was spinning Kraftwerk records on his WBLS show.

In Detroit, Charles Johnson, more commonly known as the Electrifying Mojo, commanded the airwaves via WGPR-FM. His unconstrained programming attracted a huge following, introducing his audience to obscure European imports and US acts including Prince. Kraftwerk were among the European artists receiving regular play on his show, where Numbers was a staple. In Motor City, the decline of the car industry led to a city-wide economic crash. Science fiction and technology provided optimism, a means to escape, a channel to a brighter future. The situation was similar in postwar Germany: by turning their gaze to the future, Kraftwerk offered hope and new beginnings. Their sound of the future, driven by American rhythms, resonated with the nonconformist presenter, and his support for the group was undoubtedly a catalyst contributing to the birth of techno.

Lauded by Mojo’s listeners and Bambaataa’s crowd, Kraftwerk’s music made its way into the clubs, even featuring on Detroit’s legendary Soul Train-inspired dance show the Scene, later replaced by the New Dance Show. In New York, their songs were also regular features on the dancefloor, which the group witnessed first hand when François Kevorkian took Schneider and Hütter out to experience NYC’s underground clubs in 1981. It was inevitable that their experiences in black and Latino clubs would lead to the creation of music that fed straight back into those very communities.

Juan Atkins was an avid listener to Mojo’s show. As with Bambaataa’s iconic Planet Rock, produced with Arthur Baker (another Kraftwerk fan), Atkins’ early work draws heavily on Kraftwerk’s tropes and themes. Upon hearing their sequenced drum programming, he immediately adopted the technique to mimic the group’s tight, robotic rhythms. As Model 500, Atkins used warped vocals and intergalactic computerised effects to envision the future from a Motor City perspective. (Kraftwerk’s influence also made its way to Chicago.)

New wave, early synth pop, the new romantics, London’s Blitz kids, OMD, David Bowie, Gary Numan, Visage, Depeche Mode, Soft Cell and many other groups from the post-industrial early 80s ushered in the first generation of popular music that was entirely created with electronic instruments. Initially niche, it soon went mainstream and travelled across the continent, resulting in a new wave of homegrown German electronic acts such as Boytronic, Rheingold, DAF and Stratis. In 1988, Virgin released Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit, compiled by Neil Rushton. It introduced Europe to the first wave of Detroit techno artists, Blake Baxter, Derrick May and Eddie Fowlkes among them. This first wave of electronic music, inspired largely by Kraftwerk and their electropop offspring, was the US’s reply to the German group.

As the 90s approached, radio DJs such as Monika Dietl were educating Berliners on both sides of the Berlin wall; Mark Ernestus, founder of record shop Hard Wax, was intrinsic to bringing the Detroit sound to the German capital. The fall of the wall in 1989 was pivotal: empty warehouses, factories and derelict buildings provided the perfect opportunity for the city’s large community of outliers to enjoy their newfound freedom to the fullest. Clubs such as Planet, UFO, E-Werk and Tresor became hubs for the new sound. A faction of Detroit’s second generation of techno artists had pushed the genre into a more minimal, uncompromising incarnation, which resonated with Berlin’s punks and misfits. The mood evolved to become more militaristic, the BPMs went up, the vocals disappeared, the rhythms remained monotonous and hypnotic. It transformed into a hardcore hybrid of Underground Resistance-style techno, EBM and gabba, which flourished among Berlin’s anarchistic creative communities.

Around this time, Ernestus traveled to Detroit with Thomas Fehlmann and Moritz von Oswald, with whom he later formed pioneering dub techno act Basic Channel. Their mission was to meet their Detroit heroes and gather up analogue equipment that had been offloaded at many of the city’s pawn shops. They met Mike Banks and Juan Atkins, turning up unannounced at an apartment they shared. This connection would lead to a 25-year-long collaborative relationship and friendship. Meanwhile, Tresor founder Dimitri Hegemann booked Atkins to play along with Mike Banks and Underground Resistance. Soon after the club’s launch, Tresor’s label wing appeared: their first signing was Underground Resistance as X-101. Tresor also signed two of Drexciya’s albums, Harnessed the Storm and Neptune’s Lair, and music from Atkins, Robert Hood, Jeff Mills and Blake Baxter. Dimitri inspired the conception of Atkins’ Borderland project with Von Oswald.

Once again, rhythm and musical language stimulated the flow of communication between the two cities. Underground Resistance’s anger, political commentary and paramilitary aesthetic, expressed through their uncompromising music, spoke to reunified Berlin and its hardcore punks and hippies. Clubs with virtually no rules and powerful sound systems provided an emotional outlet for the once-divided city, prompting the birth of the first generation of Berlin techno pioneers. Once that connection was made, only the UK could compete in terms of its burgeoning dance music culture and allure for international artists, though it didn’t last – 1994’s Criminal Justice Bill strangling the emergent rave scene.

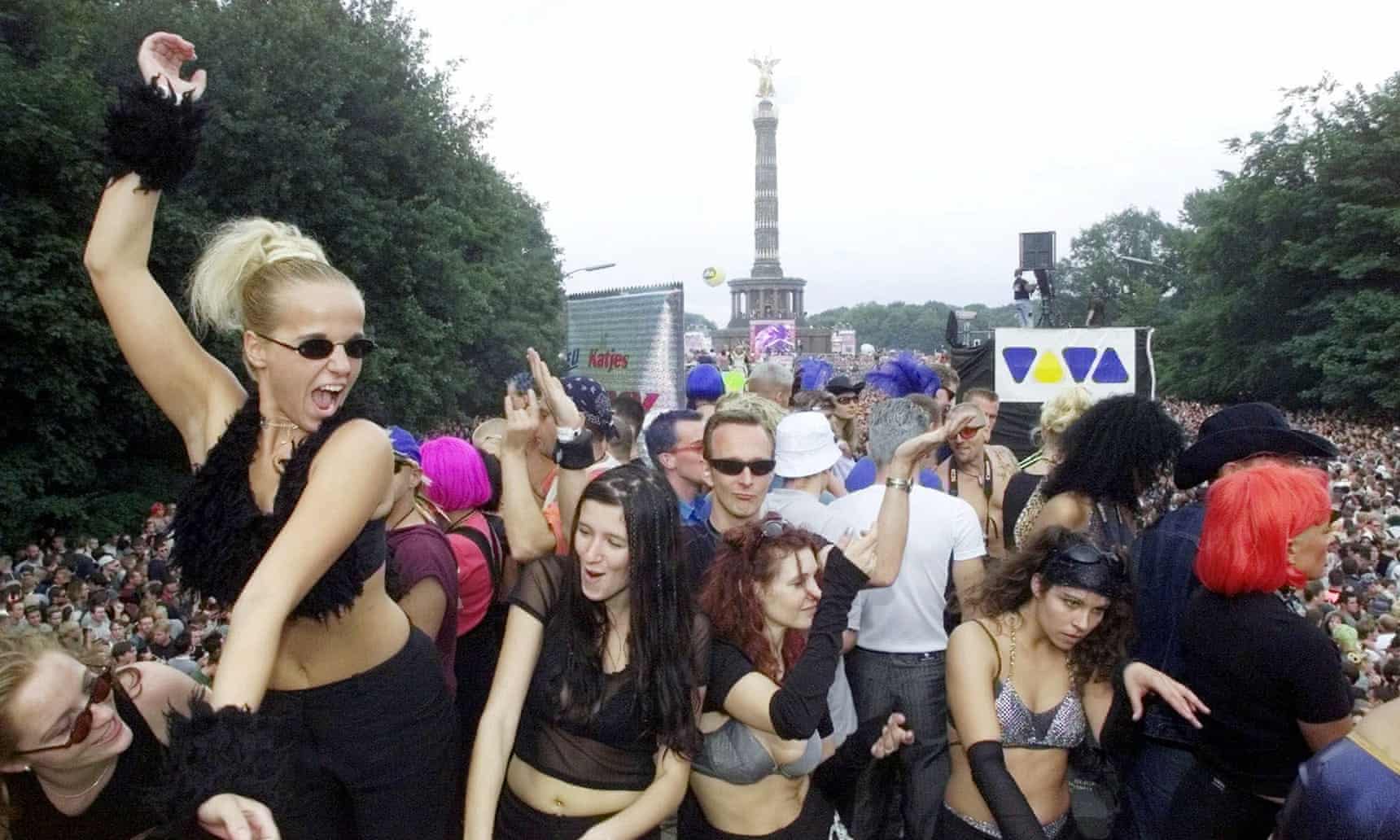

As techno’s popularity grew in Germany – Berlin’s infamous Love Parade started in 1989 and blossomed into a million-strong party by 1997, and alternative techno centres emerged in Cologne and Frankfurt – it became fringe in the US. The music moved back underground, as corporate-owned radio and TV stations shifted to commercial dance releases. It reached the point where artists from the States were playing more in Europe than they were in their own country, with a far greater number of techno clubs and festivals providing more demand and more opportunity. But the musical conversation and mutual respect between the two territories has never ceased. In the 2000s, a wave of Detroit selectors including Magda, Seth Troxler, Matthew Dear and Derek Plaslaiko migrated to Berlin. Artists such as Carl Craig and Jeff Mills became closely affiliated with their European counterparts, with both men exploring classical music with orchestras on the continent, as well as launching collaborative projects, including Craig’s long-running relationship with Moritz von Oswald and Francesco Tristano.

While national demand dipped, Detroit’s influence on the rest of the world remained consistent. At the turn of the millennium, the very first Detroit electronic music festival arrived, cycling through a few incarnations before settling as Movement in 2006. In 2016, Kraftwerk headlined, bringing their 3-D show to Hart Plaza for a kind of homecoming. Rumours about a Kraftwerk show in Detroit had been circulating for years, going back to that first festival in 2000. The group acknowledged their bond with Motor City during the track Planet of Visions, the statement “Detroit electro, Germany electro” repeating over and over.

Hütter described the link between Detroit and Germany as a spiritual connection. He was impressed “that this music from two industrial centres of the world, with different cultures and different history, suddenly there’s an inspiration and a flow going back and forth”. Kindred spirits from different backgrounds bringing people together and trying to envision a brighter future. From Kraftwerk’s Kling Klang studio to WGPR-FM, Belleville and The Music Institute, back to Berlin and UFO, Planet, Tresor, to UR headquarters, Drexciya and Motor Club, to Bar 25, Hoppetosse and Berghain, the exchange continues.