The Indian Express

Maharashtra accounts for a third of all cases, shapes Covid map

Unlike many other states, the growth of infections in Maharashtra has been unabated, and it never had any “passive” phase.

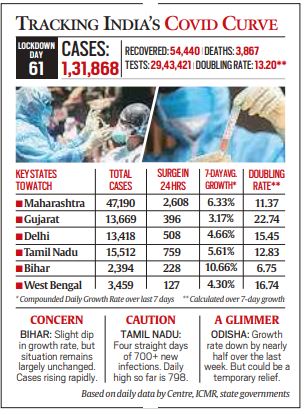

by Amitabh SinhaIn the nearly three months the Coronavirus has been in India, the one enduring trend has been the dominance of Maharashtra in the growth of Covid in the country. If anything, this has steadily strengthened with time.

On March 24, when the first countrywide national lockdown was imposed, Maharashtra had one-fifth of all the Coronavirus infections in the country. Two months later, as India’s caseload has gone past 1.3 lakh, Maharashtra’s share has increased to more than one-third. In the last ten days, more than 40 per cent of new infections detected in the country have come from Maharashtra.

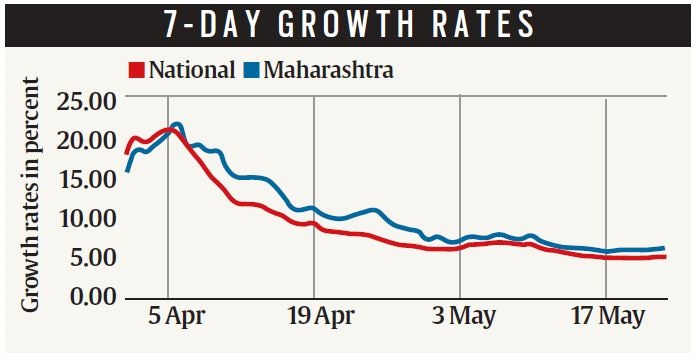

Such is the dominance that whenever Maharashtra has managed to slow down its growth for a while, it has slowed the national growth rate as well. And, the opposite has been true as well. In fact, the curve for the national growth rate very closely resembles that of Maharashtra (see chart). Same is true when it comes to doubling time of cases.

In other words, if the outbreak in Maharashtra is somehow contained, or its growth slowed down, a sizeable part of the problem in the country would be taken care of. But doing that is easier said than done.

Read | Maharashtra minister Ashok Chavan tests positive

“From a containment perspective, it is good if a large number of infections are concentrated within a small geographical area. Theoretically, this entire area can be isolated, and movement to and from this area can be restricted. Even in Maharashtra, the entire state is not equally affected. An overwhelming number of infections are just in the two cities of Mumbai and Pune and their suburbs. It is this one contiguous region that is the biggest problem area. Theoretically, if we are able to ensure that no infected person goes out of this area, eventually the disease will tire itself out in this area, without contributing much to the spread elsewhere,” said Sitabhra Sinha of the Institute of Mathematical Sciences in Chennai who has been tracking the spread of the disease. But the idea of putting entire cities under quarantine has huge practical difficulties, especially if the cities are as important for financial and industrial well-being of the country as Mumbai and Pune.

Gautam Menon, a professor of computational biology and theoretical physics, also at the Institute of Mathematical Sciences, said containment would probably have been easier if, instead of being in Mumbai, a similar number of cases were located at some other place even if the geographical spread was a little more than the size of Mumbai.

“In a way, Mumbai is representative case of how difficult it is to contain an infectious disease in dense urban settings. A similar situation is being played out in other cities like Ahmedabad, Delhi, or Chennai as well. But, even amongst these cities, Mumbai probably presents the most complex challenge. I am not very surprised to see that it is Mumbai where we are seeing this kind of growth and not any other city or region,” Menon said.

Unlike many other states, the growth of infections in Maharashtra has been unabated, and it never had any “passive” phase.

Sinha said this was not unusual. “In fact, Maharashtra is probably the only state which has followed an almost textbook example of an epidemic curve. The growth did slow down a bit because of the lockdown but, overall, the curve is exactly what one would expect it to be. In many other states, there have been disruptions, caused either by specific triggers like a super spreader event, or reporting of inconsistent or low-quality data,” he said.

What has been a little unexpected, however, is the fact that reproductive number for Maharashtra has continued to decline even more than two weeks after the lockdown easing. The Reproductive number, or R, is the average number of people who get infected by an already infected person, and is a very good measure to assess how fast an infectious disease was spreading in a population.

“Right now, the R-number for India as well as Maharashtra are at the lowest point during this pandemic. I was expecting this value to begin rising by around May 15, as a fall-out of the relaxation in lockdown rules. The R-number for Maharashtra is a little higher than that of India as a whole, but it is still at its lowest, and that is a bit surprising. I would wait for a few more days to see whether this is a temporary blip, or part of a larger trend. I am expecting the R-number to rise, and consequently there is likely to be a surge in Maharashtra numbers in the coming days,” Sinha said.

More so when domestic airline services resume operations Monday and industrial and other activities in areas outside of municipal limits of Mumbai and Pune have got a go-ahead to re-start work.

The task is cut out, said Vineeta Bal, an immunologist at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) in Pune. “Eventually, how successful we are in containing the spread of the disease, especially in a city like Mumbai, will depend to a very large extent on how empowered and effective local authorities are in dealing with this crisis,” she said.