Architecture

There's a fighter jet on the pavement! Wonders of the Soviet roadside revolution

From tractors on poles to a fighter jet taking off, Russia’s roadsides are still dotted with celebrations of Soviet vehicular prowess. And now a French photographer has captured their strange allure. See gallery here

by Oliver WainwrightA ship teeters on the crest of a concrete wave in the Russian port city of Novorossiysk, its anti-aircraft guns pointing to the sky. One thousand kilometres away, outside Bohodukhiv in Ukraine, a tank stands on a cantilevered roadside plinth, looking as if it’s about to be fired off a diving board. Meanwhile, on the Baltic coast of Kaliningrad, a crumbling mermaid with a faded smile hovers above a swirling expressionist sign welcoming people to the seaside town of Yantarny.

These are just some of the curious fragments gathered from the farthest-flung corners of the former USSR, brought together in a new book, Soviet Signs and Street Relics. It is the latest volume from Fuel – publishers of such classics as Soviet Bus Stops and Russian Criminal Tattoos – and it’s a fitting travelogue for our constrained times. Unlike these previous surveys of communist relics, photographed in the flesh, these have been collected via Google Street View.

French photographer Jason Guilbeau spent months travelling thousands of miles, from Vladivostok to the Baltic Sea, all from the comfort of his computer, searching for strange roadside remains of the Soviet empire. The results are a haunting mix of forlorn military symbols, creaking monuments to agricultural prowess, and plenty of space-age swooshes, swirls, stars and arrows pointing towards a bold utopian future that never quite arrived.

In the introduction, architectural historian Clem Cecil describes how the road network in the Soviet Union assumed a huge significance, as the population was urged to be peripatetic. Young couples were offered jobs the length and breadth of the country, far from their original homes, while others were encouraged to be pioneer settlers in new regions. The roadside monuments served as a continuous backdrop to the endless journey, reinforcing the messages of Soviet ideals and victories. “Like bystanders cheering on marathon runners,” Cecil writes, “roadside propaganda was there to work as a morale booster in the exhausting collective endeavour.”

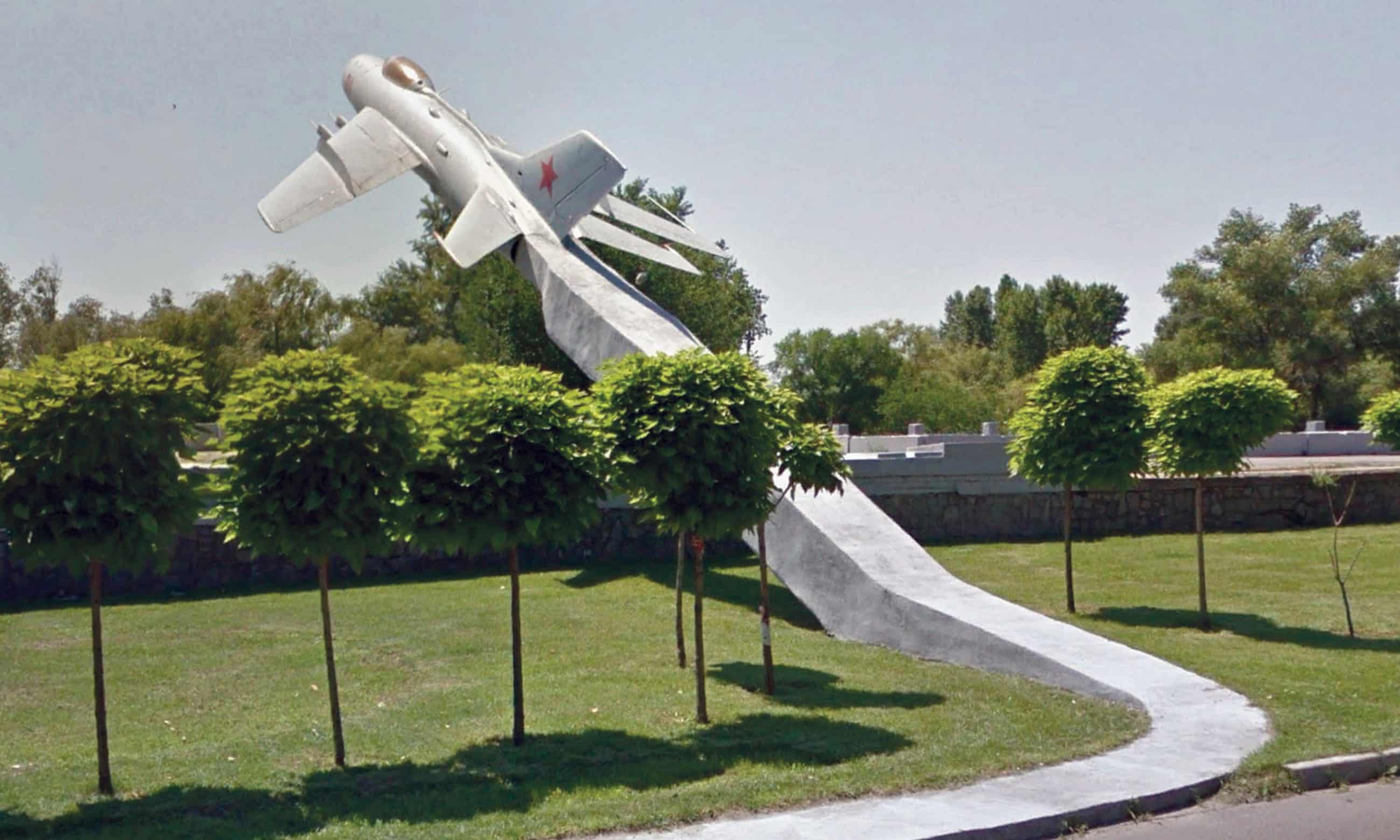

Transport is a recurring subject for the sculptures, with cars, trains, boats and planes joined by tractors, pickup trucks and – later – dazzling space rockets. The message is clear: the Soviets had conquered movement in its every form. A shining rocket rises from a field outside Lipetsk, captured in motion above a blue and yellow sunburst. The depiction of movement reaches an artistic climax in Dnipro, Ukraine, where the entire pavement is co-opted into the tableau, swerving dramatically away from the road, breaking through a line of trees, and rearing up to become the concrete vapour trail of a fighter jet, frozen in mid-takeoff.

Elsewhere, bathos is the order of the day. The final spread in the book shows a rusting steam engine sitting on a fat column in the middle of an overgrown cobbled plaza, opposite a trio of tractors in various states of disassembly, perched on raw concrete poles. They look like flotsam stranded after a flood, or the result of a student prank, the vehicles jacked up into unlikely spots from where they will never be retrieved.

It is possible to read, in their various states of decay, the breakneck speed at which these structures were often erected, as part of a mass propaganda campaign across the vast USSR, often replacing religious or tsarist monuments. Cecil quotes Russian historian Mikhail Yampolsky: “The point was to replace some monuments with others quickly, as if the emptiness created by the broken idols possessed some sort of destructive force that had to be subdued.”

In turn, the broken state of most of these roadside structures could today be read as its own destructive force, a reminder of the failure of the Soviet project. Which poses the question: why haven’t they been removed if they serve as painful souvenirs of the recent past? “Perhaps these objects persist because of their invisibility,” writes Cecil. “Nobody sees them any more.”

Equally, they might persist because they have become much-loved local landmarks. Who wouldn’t be cheered by the sight of the big plump watermelon, freshly sliced open and proudly displayed, on the corner of a street in Kherson Oblast? What child would not be entranced by the gigantic lump of coal framed inside a big red starburst, celebrating the Sibirginski open-cast mine in Kemerovo?

Whatever their fate in the real world, these relics will live on in the omniscient cloud of Google Street View, the roadside propaganda of the former communist empire mapped in minute detail by American big tech.