SpaceX overcame parachute, thruster problems in Crew Dragon development

by Jeff FoustWASHINGTON — To get a new, state-of-the-art crewed spacecraft ready to carry astronauts, SpaceX and NASA had to overcome problems with a technology long thought to be understood.

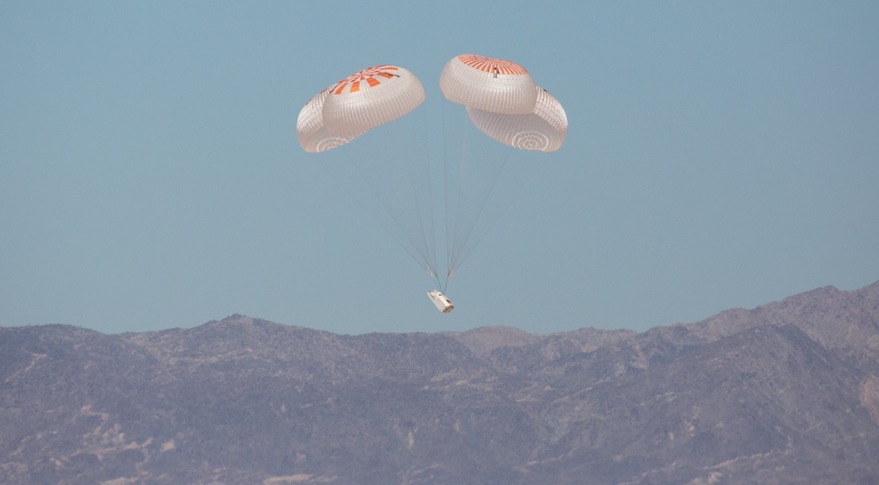

One of the last tests that SpaceX had to complete for the Crew Dragon was for its Mark 3 parachute system. The company announced May 1 that it successfully carried out the final test of the parachute system, with 27 tests overall carried out since last fall.

The company said last fall it was switching to the new Mark 3 design to provide greater safety margins. SpaceX suffered at least one failure of the Mark 2 parachute system in a test in April 2019, one that was revealed in a congressional hearing a few weeks later.

“We established a little while ago that the original chute design did not have adequate margin, based on some knowledge we had gained through testing about how the chutes deploy and the loading on the chutes,” Steve Jurczyk, NASA associate administrator, said during a May 22 briefing after a day-and-a-half flight readiness review for the Demo-2 mission that he chaired.

Despite decades of experience with parachutes of various types, the parachutes developed for Crew Dragon posed a new problem, called “asymmetric loading,” that caused the parachutes to fail in some situations. That problem puzzled many parachute designers.

“The problem that Dragon has really enlightened the community and basically forced us to go out and understand what this problem is,” said Robert Sinclair, chief engineer with Airborne Systems, in an interview in December. That included “asymmetry summits,” where parachute experts around the world convened to discuss the problem.

The work included instrumenting parachutes with sensors to measure loads as they deployed, and using that data to update models to inform new parachute designs. “That one thing that SpaceX found when they had that problem has enormously helped the entire recovery system community.”

While the tests of the Mark 3 parachutes went well — the only reported mishap was March 24, when a problem with a helicopter forced an early release of a test article before the parachutes were armed — the Mark 3 parachute system was still a subject of scrutiny in the flight readiness review.

“The NASA/SpaceX team did an amazing job laying out a test program and executing that test program,” Jurczyk said. “However, it’s fewer tests than we would normally see on a parachute qualification program.”

“We took a long time in a couple of presentations during the review to have the team walk us through the design, the changes, the qualification testing and the margin on the chute to make sure that everybody was good with how the chutes were qualified,” he continued. “We have very high confidence that they will function as we need them to when Bob [Behnken] and Doug [Hurley] return from the International Space Station.”

Besides the parachutes, one of the other major issues was the launch abort system. A Crew Dragon spacecraft was destroyed in a static-fire test of the SuperDraco thrusters used in that system in April 2019, an incident that was blamed on a slug of nitrogen tetroxide (NTO) propellant that, when the thruster was pressurized before firing, was accelerated into a titanium valve, igniting it.

SpaceX corrected the SuperDraco problem and successfully tested the overall launch escape system in an in-flight abort test in January. Jurczyk said that nitrogen tetroxide/titanium “compatibility issue” was another subject of discussion in the flight readiness review. “There were a lot of questions to just understand where we were and to make sure that we were ready to accept that residual risk there for the Demo-2 flight, which we are,” he said.

That included, he said, extensive testing by NASA at its White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico and by SpaceX at its McGregor, Texas, engine test site. SpaceX in particular over the last few weeks “has done a tremendous amount of testing, and that testing gives us confidence that we have a system that is going to perform, and we’ll have that abort capability.”

That confidence wasn’t always as strong. Kathy Lueders, NASA commercial crew program manager, noted at the briefing that, prior to the SuperDraco anomaly, the agency thought it could fly the Demo-2 mission by the end of 2019. “Last April I probably wasn’t thinking I was going to be flying in a year,” she said.

However, she noted that the accident helped them better understand the abort system, including compatibility of materials with nitrogen tetroxide, resulting in an improved spacecraft. “That was a real blessing for us. We learned a ton about our system,” she said. “Don’t ever underestimate the value of a failure.”