Planning, Creativity Keep National World War I Museum And Memorial Staff Employed Through Closure

by Chadd Scott

Cultural workers have been devastated by coronavirus closures. With their workplaces nationwide shuttered to the public, they have been laid off and furloughed by the thousands.

The American Museum of Natural History in New York announced in early May it would be cutting roughly 200 full-time staff positions and putting another 250 full-time employees on indefinite furlough. The Broad art museum in Los Angeles has laid off 129 part-time employees. The Museum of Science in Boston has furloughed 250 staff members and laid off 122 more. The Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas has eliminated 168 positions.

From big cities to small towns, all across the sector, museums, dependent upon earned-revenue for their existence–ticket sales, gift shop and restaurant receipts, special event rentals–are hemorrhaging money and employees.

One exception is the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City. None of its 42 paid staff members has been laid off, furloughed or experienced any reduction in hours since the institution closed to the public on March 14.

Thanks for this goes to years of financial preparation for a catastrophe it could not predict and a unique program transitioning employees from their regular responsibilities into transcription of the museums thousands of hand-written correspondence.

“We already have a lean team and so in order for us to serve our audiences, I really wanted to preserve the staff,” National World War I Museum and Memorial CEO Matthew Naylor said. “I worked with our finance team to figure out how we could do that and then with our board to reach an agreement about how much (money) we're willing to lose.”

While Naylor considered layoffs and furloughs, and the museum projects to lose over $2 million in revenue as a result of being closed, he said the museum’s board of directors strongly supported the plan not to cull staff.

“We were able to demonstrate (to the board) that refocusing the staff would really strengthen our work,” Naylor recalls. “We have a lot of momentum and I think that (the board) accepted the argument that refocusing the staff would continue to keep the momentum going even at a bit of a slower rate, but for us to essentially stop activities could have a pretty negative impact on the work that we do.”

That “refocusing” began in early February, weeks before many other institutions took the threat of COVID-19 on their business seriously. The National WWI Museum immediately identified it as a threat and began financial modeling around its potential impact. It also started brainstorming what to do with staff members?

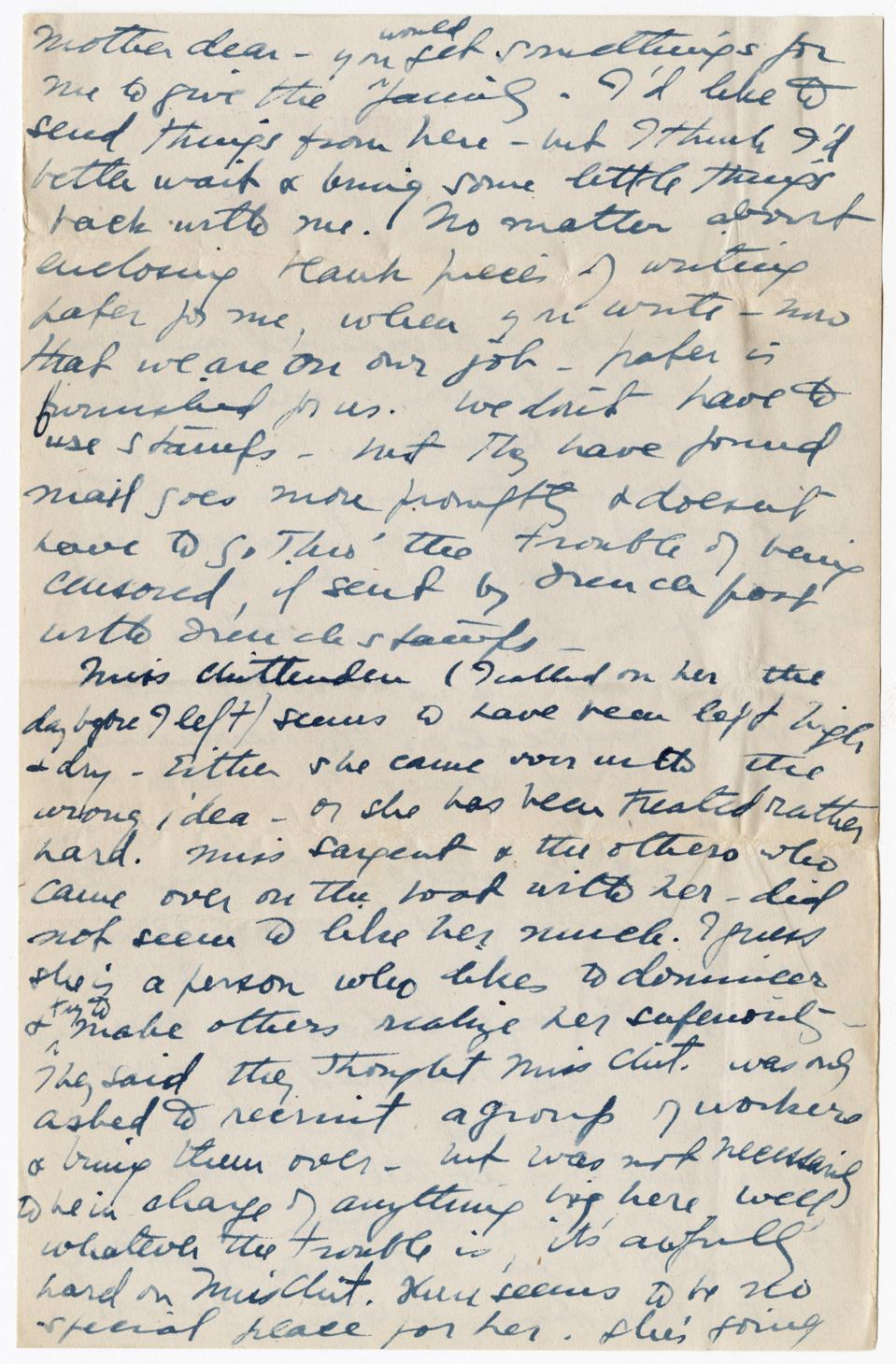

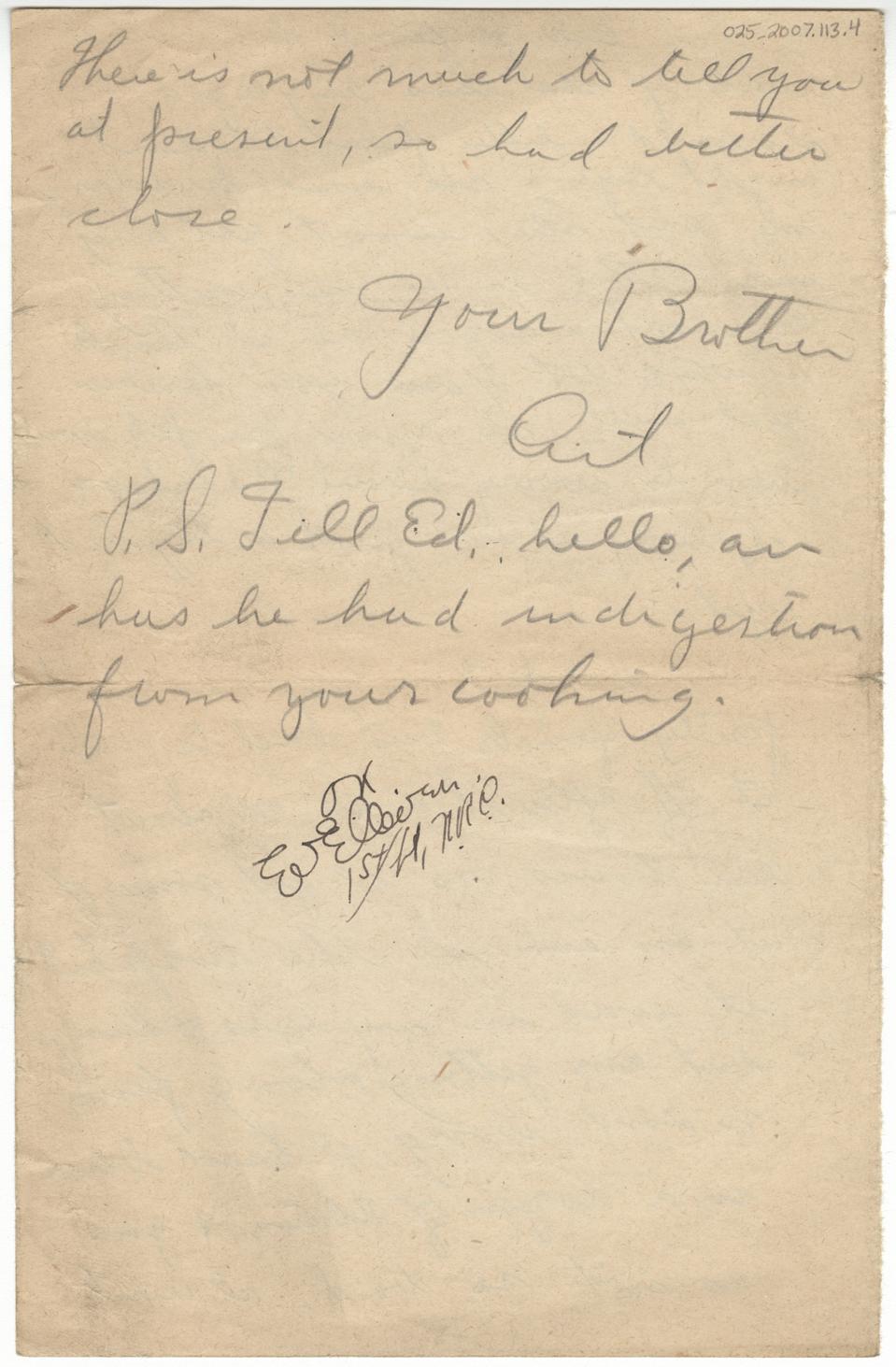

From a variety of suggestions, a transition to home-based transcription was agreed upon as the best solution. On March 24, 17 staff members were reassigned to transcription, bolstering that department’s regular staffing of three. Since then, those extra human resources have resulted in over 6,000 pages of letters, diaries and journals being transcribed and digitized.

All of which further bolsters the museums on-line offerings and efforts to make its holdings more accessible. With the handwritten documents transcribed and digitized, they can now be translated into other languages and accessed more easily by the visually impaired.

Another long term benefit will be experienced by museum visitors. Employees who previously had little first-hand knowledge of the war will now possess a reservoir of stories to share following their two months spent with the documents.

“I'm excited to get to talk more about these specific perspectives or being able to talk about, ‘Oh, do you know that some soldiers saw these sorts of things,’ or really being able to give a better mental image of the sorts of things (soldiers) are seeing,” museum employee Margaret Witzke said of how transcribing will better inform her future interactions with guests.

Witzke had been a guest services associate since starting at the museum in October of 2019, selling tickets and working in the museum store.

One letter home from a soldier particularly stands out to her. This man, doubly upset about being passed over for an expected promotion and forced to stay in France after the armistice while the rest of his squadron was returning to America, took the squadron Cadillac on an unauthorized three week road trip through Europe.

While the trauma of war is shared in the letters, so are the mundane activities of military life and humor.

“Many of the staff who have been working on the transcription project are ordinarily a frontline staff working with guests, so they do not spend time with archival materials,” Naylor said. “For many of them it's been an extraordinary experience because they have spent the last weeks reading letters, reading journals and diaries of the soldiers who served, and so it's been very meaningful for them, they're saying this has been just fabulous, such a great enriching experience as a relates to their work.”

What of the penmanship?

“I have always joked that I'm so glad I'm not in a Jane Austen novel because I could never convince someone to fall in love with me with (my) chicken scratch,” Witzke said. “I simultaneously feel better and worse about my own handwriting dealing with these–some people have gorgeous handwriting, some people it takes you eight hours to get through one page.”

As with any crisis, the best time to prepare for it is not as it is happening. Naylor has been preparing his institution for the financial crisis his industry now faces for years. That preparation came in many forms from cautious revenue projections, annual questioning of department heads about where cuts could be made if projections weren’t met, and several years’ worth of revenues exceeding expenses allowing the institution to build cash reserves.

That last fact, more than any other, Naylor admits, is what has allowed him to maintain his staff.

“One of the challenges that the nonprofit sector faces across the board is having sufficient working capital,” Naylor said. “We have worked hard over a number of years to have what we thought was an appropriate level of working capital in order for us to weather storms.”

When thinking about working capital, Naylor thinks about “days,” not a specific figure.

“How many days of working capital were needed, and this has been a debate for us for a number of years,” Naylor said.

He arrived at 180 days of unrestricted working capital accessible and available. The museum began the year with 155.

“Now, of course, we’ve eaten into that very considerably, but had we not had that we wouldn't have been able to do what we do,” Naylor said. “Sometimes in the sector there's a view that one shouldn't be accumulating, but it's about responsible financial management; many organizations, they’re not in that privileged position, but it was a policy and a practice, culturally, for us in the board and senior management for us to build that.”

While Naylor has been able to retain museum employees, outsourced workers such as security, custodial and food service contracted through vendors haven’t been similarly protected. The WWI Museum also benefits from 300 volunteers.

Fortunately for everyone involved, the museum will reopen to members on June 1 and again to the general public on June 2.