This New Zealand Artist Looks To The Stars To Discover How Humans Have Tried To Map Their Place In The Universe

by Y-Jean Mun-DelsalleGazing at the stars is something that Berlin-based, New Zealand artist Zac Landon-Pole has been doing for some time now. He had contemplated celestial mapping through his Passport (Argonauta) creations where meteorites were hand-carved to fill the apertures of fragile paper nautilus shells made by an octopus. “I’d been thinking about things from the depth of the sea and then the depth of space, this in-between space between borders and between national territories,” he says. “Collapsing those two dimensions together into these strange hybrid or synthesized objects was already a lens through which I was thinking about space. One thing I learned about meteorites in researching more was how scientists used them to understand what the universe was like before the earth even existed because some of them are carbon dated to 4.5 billion years old. That idea of the depth of time, the limits of our own conceptions of time and how that might register across geological time or the ways that people structure time have very much to do with the ways that people map the stars.”

Forming part of a recent body of work, Langdon-Pole’s photograms speak about deception, not necessarily believing everything you see and how easy it is to deceive, as well as serve as documentation of sites that are being threatened by two prevailing forces of climate change: the erosion and submersion of shorelines, and the desertification of inland territories with mass movements of people. Resembling a starry night sky with its bright white dots set against an inky black backdrop, the photograms were actually made using sand samples he had collected from specific locations like the Marshall Islands or Berlin, stops along his four-month-long BMW Art Journey – a collaboration between Art Basel and BMW to support emerging artists globally – completed in 2019, which saw him traveling from Europe to the Pacific Islands to explore the differences and similarities between how people have mapped the stars throughout history.

“There’s not a message there as much as there’s a context that I think deserves attention,” Langdon-Pole notes. “There are so many different facets to what sand is and how culturally it has been treated within the history of literature. It pairs with this idea of the infinite, an hour glass as a qualifier or quantifier of time or as something that’s about erosion, decay and entropy. Sand is super loaded, but when I realized I was doing this travel project and the lens of looking through the ways that people have mapped the stars, this fell together for me from different angles. I was trying to think about the most impossibly big thing that I could do, and the irony is not lost on me that I made these works out of something small that fits inside my pocket in response to the grandeur of this opportunity.”

Unlike other artist collaborations where the artwork must relate to the brand’s heritage or values, what’s unique about the annual BMW Art Journey is that the winner has the opportunity to crisscross the planet without having to worry about the budget or even having to create any artworks. Chosen by an independent jury of internationally-renowned curators and museum directors, artists are encouraged to imagine a voyage that’s as ambitious as possible. “The beauty of this program is that there’s not a great expectation that everything you do should become art,” Langdon-Pole discloses. “It’s an amazing generosity and privilege to travel purely to go see things and not for it to be qualified or quantified in a productive output sense since a lot of my work is quite slow. It can take years in conceptualization or until it just feels good.” From France’s Lascaux caves to view a prehistoric map of the night sky dating back at least 16,500 years to the Mauna Kea Observatories in Hawaii to explore the dominance of Western astronomy on indigenous perspectives, his research encompassed ideas of time, navigation, colonization and migration. He sought to discover how humans have tried to map their place in the universe over millennia, and consequently raised greater existential questions about who we are and our place in the world.

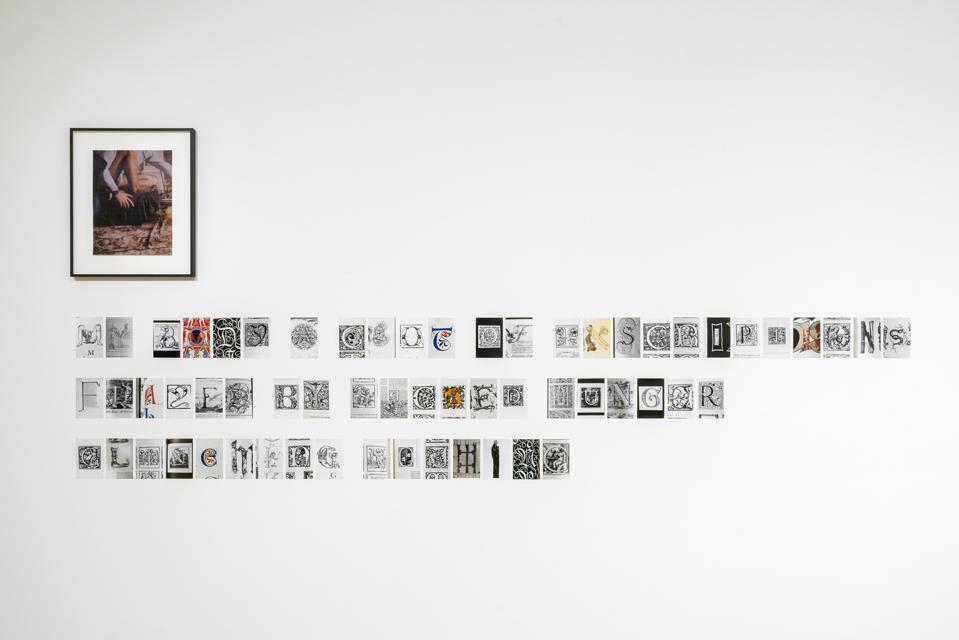

Born in 1988 in Auckland, Langdon-Pole had planned to become a professional swimmer before art studies during high school changed his mind. “The darkroom was a magical place, seeing an image appear on a piece of paper, and it was an amazing social space as well,” he recalls. “I had wonderful friends I’d spend time with there, so photography was my way in to art.” Heeding his art teacher’s advice, he applied to the University of Auckland’s Elam art school. “As soon as I got there, I loved it; it was where I found ‘my people’,” he admits. “In New Zealand, there’s such a tight-knit, wonderful community of artists, and I felt fortunate to realize that the art world wasn’t some ridiculous, elitist or scary thing.” Tackling questions of belonging, translation and identification, his works have explored the gaps, relations and interpolations between cultures, generations and eras by mixing images, objects and histories from specific origins. Easily shifting between painting, photography, film, sculpture, poetry and installations, in Paradise Blueprint, he displayed taxidermied birds of paradise with legs severed according to Papuan preservation tradition, which had led to false speculations in the 16th century by European naturalists as to why they had no feet, and produced a wallpaper based on the patterns created by the removed legs; while in My Body… (Brendan Pole), he reconstructed a lost poem of his late uncle through forms of oral history that had only existed as a recollection of a memory.

For his 2015 graduation project while at Frankfurt’s Städelschule art academy, Langdon-Pole sent his professor, Willem de Rooij, to New Zealand to stay with his family and friends and in turn produce a specific photograph for him. “It was in some ways a provocative gesture, but in other ways a thank you,” he explains. “As I’m crossing this threshold of graduating from your class, maybe you could learn from me, where I’ve come from and what kind of world I operate within, so him being there, that moment of encounter between worlds, is one guiding post that underpins my work. Everybody comes from somewhere and we’re always increasingly moving through this world, but what happens in that space between is an interesting point to start from because of course art is that already. It’s the space between me as an artist and you as an audience, and that relationship is far more dynamic than any classical idea of art would prescribe to.” When asked if he’s trying to convey a message through his art at the end of the day, he replies, “I kind of fear that that shuts it down. Maybe if there is a message, I’d just tell you. I think art can say more things than one possible thing at once, and it can say things in contradictory ways and from different perspectives.”