What's So Great About Self-Knowledge?

5 reasons why understanding ourselves is essential for psychological growth.

by Anna Katharina Schaffner, Ph.D.

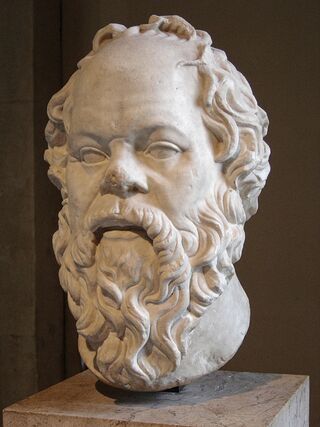

The maxim “Know thyself” is so ubiquitous that it has become a personal development cliché. But knowing ourselves – truly understanding who we are – is by no means easy. The ancient Greeks knew this well and carved the motto above the portal of the Temple of Apollo. Socrates (470–399 BCE) went even further, declaring that the unexamined life is not worth living. While he put it rather starkly, it is true that if we remain in the dark about our natural preferences, our core strengths and weaknesses, our values, and our hopes for the future, we will find it very hard to live coherent and fulfilling lives. Above all, we will be lacking in control: If we do not understand our basic motivations and fears, we will be tossed around by our emotions like small vessels helplessly adrift on a choppy sea. Ruled by forces that remain incomprehensible to us, we will not be able to navigate towards the shore.

How can we best acquire this most precious form of knowledge? First and foremost, we can rationally analyze our cognitive processes. CBT-style approaches will give us a good indication of our recurring negative thoughts and the areas in which our cognitions may be distorted. Mindfulness-based techniques are particularly useful for honing our emotional intelligence, and for disinterestedly observing our emotional reactions. The psychologist Daniel Goleman understands emotional intelligence as a form of meta-cognitive awareness that is manifest in “recognizing a feeling as it happens.” The “inability to notice our true feelings leaves us at their mercy,” he writes.[1] There is a vital difference between simply being caught up in a feeling and developing an awareness that we are being submerged by this feeling. Objective self-observation is therefore crucial for knowing both our cognitive and emotional selves.

We can also travel into the past to conduct some existential detective work, in order to understand how our experiences may shape our reactions in the present. The founding father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, argues that our mind is like an iceberg – only a small part of it is above the waterline, whilst the rest drifts in the murky depths of our unconscious. Only when we pull our darkest fears and desires into the light of the conscious mind, where we can examine them calmly and analytically, will they begin to lose their monstrosity, and much of their influence. What we do not know consciously – the repressed – is the true “other” to genuine self-knowledge.

To gain a basic understanding of our natural preferences and core strengths and weaknesses, we can also study personality-type theories and fill out psychometric tests. The idea that we can be classified according to our temperamental type can also be traced all the way back to ancient Greece, and, more precisely, to the physician Hippocrates (ca. 460–370 BCE). We can still feel the repercussions of Hippocrates’ typology today, in Jungian-inspired psychometric personality tests such as the MBTI and Insights Discovery Profiles, for example. These can be starting points in our quest for self-knowledge, helping us to understand our inclinations and natural powers, and pointing to areas we might wish to develop further.

Finally, we can of course enlist the help of others, such as therapists, analysts, and coaches, on our quest to make better sense of our past and our present. By working with transference or asking us challenging questions that encourage us to view our problems from a new perspective, they can transform our negative narratives about ourselves into kinder and more productive ones.

The crucial question, however, remains: Why should we aspire to self-knowledge in the first place? There are five core reasons:

- Self-knowledge directly relates to one of our basic needs, the desire to learn and to make sense of our experiences. This includes acquiring as much knowledge about our own patterns, preferences, and processes as we can. As in other domains, the more deeply we understand something, the better we can master it. And who doesn’t want to be master in their own house?

- The opposite of self-knowledge is ignorance – about who we really are, our true motives, our deeper patterns, and how we come across. Self-knowledge prevents a discord between our self-perception and how others perceive us. Delusional assessments of our skills and qualities, in the form of “unrecognized ignorance,” can be the cause of great embarrassment when they are unmasked.[2] If our perception of ourselves rests on unsound foundations, we will invest much of our energy in defending our self-image against the threat of cognitive dissonance. Because we have much to hide, and much to lose, we will find it hard to relate to others authentically and openly.

- Freud would argue that self-knowledge emancipates us from being a slave to our unconscious and its many seemingly so irrational whims. Only when we know our patterns, and where they came from, can we manage them effectively. Understanding our histories keeps us from blindly repeating unproductive past patterns. It can also result in a kinder and more compassionate view of what we may regard as our failures.

- Crucially, self-knowledge enables us to be more proactive in response to external events. If we truly know our patterns, our triggers, and our pleasures, and if we have the emotional intelligence to recognize our feelings as they happen, we are much less likely to be dominated by them.

- Finally, self-knowledge is also the necessary first step for initiating positive change. Only by taking stock of what is – in as objective a way as possible – can we plan what we want to change and work towards it.

Self-knowledge, then, quite simply improves our chances of making wiser choices. It turns us into better pilots of our lives, yielding mastery and realism, as well as congruence and alignment. It will also make us more humble. For as Socrates knew well, a vital part of self-knowledge is also knowing what we don’t know and openly acknowledging our ignorance.