Fear

The Rabbi and the Pandemic

Crossing the bridge of fear

by Ahron Friedberg M.D.THE BASICS

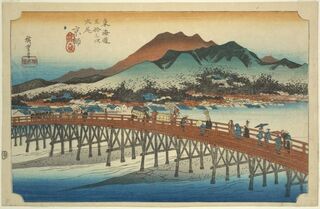

An epigram attributed to the Hasidic rabbi Nachman of Breslov (1772-1810), seems appropriate just now: “The whole world is a narrow bridge, and the essential thing is not to fear at all.” This notion of the world—shaky, spindly, not easy to navigate—has passed into song and is the title of a recent novel, Aaron Thier’s The World is a Narrow Bridge (2018). Nineteenth-century Jews had a talent for describing impending disaster.

Yet while this epigram seems poignantly appropriate to the world of COVID-19, and we should take it to heart, it is not what Nachman actually said.

Research by a modern scholar, Rabbi Daniel Pressman, demonstrates that what Nachman said is actually more nuanced, indeed more modern in that it throws responsibility for making one’s way specifically onto the wayfarer: “When a person must cross an exceedingly narrow bridge, the general principle and the essential thing is not to frighten yourself at all.” The more famous, but inaccurate version of this saying is an example of Jewish “telephone,” where meaning curves and warps and is ratified by repetition in popular culture.

Apart from the vagaries of Hebrew translation, however, the actual version of Nachman’s saying calls on us not to originate fear— not to be its first-instance cause. This imposes a heavier burden than imploring us not give into fear that is already present in a world that, like a narrow bridge, creates an environment of fear through its mere existence. The real epigram demands self-control, perhaps even belief that on either side of the narrow bridge there is hope. It’s the difference between the world’s being a narrow bridge—which is a pretty encompassing idea, likely to frighten anyone—and there being a narrow bridge in the world, which we can navigate if we take control. So apparently, according to Nachman, fear comes from ourselves. We can repress it by not originating it in the first place.

I think about Nachman as we emerge on Memorial Day like soldiers emerging from bunkers. We stick our heads up an inch or two and worry that the enemy may mow us right down. I can see the irony, since I’m not supposed to feel like someone in a war movie on Memorial Day; I am supposed to remember real soldiers. But it’s how I feel. It’s how we all feel in the upended world of COVID-19.

So, what would Nachman have to tell us today? He would talk about courage. He would not say not to be afraid, but he would cite the examples of other people on the bridge who are still moving along. Don’t look down. Look ahead. Keep going. One of my patients once told me that when she trekked the Himalayas, there were all these narrow bridges over rivers and gorges. At first, she was terrified, but she watched how the Sherpas crossed and tried to imitate them. They never looked down. I think they would have been amused at the notion of some Hasidic rabbi... but they applied his principle. So she did too.

During the course of this pandemic, I’ve introduced Nachman to several physicians on the front lines who are stressed, traumatized, and burning out. My regular practice is full of people in need. I tell them all to keep looking in front of them, to keep going, to acknowledge what is scary but not to nurture fear. That is, not to project horrific outcomes based on our own worst imaginings. I think that is what Nachman is getting at—while we cannot just put fear aside, we must not ruminate on it and allow it to take over our lives. We must not be the source of our own terrors.

In Nachman’s sense, fear is like the virus. It cannot replicate outside human beings but, once inside, humans become its agent. Nachman is the great epidemiologist of fear: His warning is that we not allow ourselves to be complicit in allowing fear to grow.

Many people have had to overcome fear. For example, my patient John is an art dealer in his mid-thirties. He had broken up with his live-in boyfriend before COVID-19, and was still trying to cope with life on his own. Moreover, because he is black as well as gay, he is self-conscious in an art world that is largely white. When he heard the recent news of a black man who was shot in Atlanta while jogging, he got concerned. But then he went out for a run.

John had been on the track team in college, and running made him feel strong. It was a source of self-esteem. He could have let it become a reason to fear, but he turned it to his advantage.

But perhaps even braver is my patient Sherry. She’s an accomplished writer in her seventies; never married; more on her own just now than she would prefer. During the pandemic, she remained in her apartment, except to pace the hall and pick up the mail. “What am I supposed to do if I get sick?” It’s a fair question. But life is a series of trade-offs.

Over the Memorial Day weekend, she wanted to mail some letters, in particular her application for an absentee ballot. The deadline was early June. She debated whether to venture out, and decided that having to show up in person for the June 23 primary was a greater health risk than crossing the street to the mailbox. After all, she is well-equipped. She has N95 masks and latex gloves. She understands social distancing. I urged on her the benefits of fresh air and explained that the viral load is lower outside than on a crowded bus or in an emergency room. So, she took the plunge.

When we spoke, she told me that the sun felt warm, like an old friend. Before she knew it, she had walked to the mailbox and then a few blocks more. In effect, she had crossed the bridge. Just as John had. Both of these frightened people kept looking ahead, rather than down. John knew he was a runner and wasn’t about to forsake it. Sherry knew she wanted to cast a mail ballot, and (literally!) took steps to make that possible. Neither of these people allowed themselves to proliferate fears that, like the virus, will multiply exponentially if we give it a favorable environment.

I really like this idea of a bridge in the world. We are not crossing to a better world but learning to traverse the troubles in this one. We are making up our minds to traverse them. My patients put one foot in front of another—and they are still here.