Yes, that Harriet Tubman debit card is real, and no, she’s not supposed to be doing the Wakanda salute

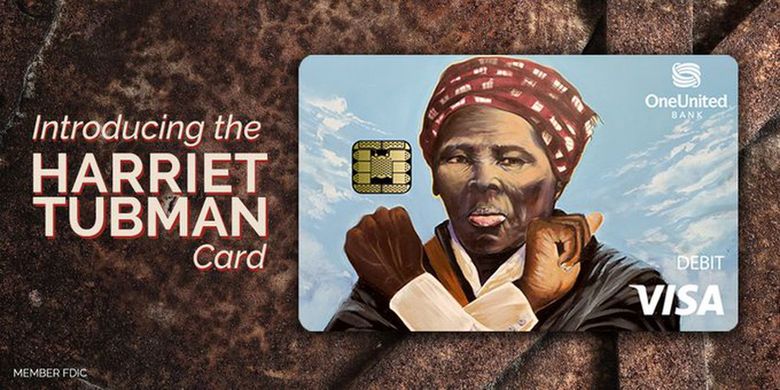

by Teo ArmusThe image depicted Harriet Tubman gazing forward, wearing a serious look and a red-and-white headwrap, in a design that seemed to resemble one of the more famous photographs of the abolitionist.

But Tubman’s pose was different from the one in that photograph, and oddly familiar: The abolitionist was crossing her arms over her chest in an X and balling her hands up into fists — kind of like the “Wakanda Forever” salute from the movie “Black Panther.”

Oh, and the image was printed on a debit card, with a gold chip above her right shoulder and the Visa logo on her left.

It would be difficult to elicit a stronger mix of ire, confusion and utter disbelief than OneUnited Bank did on Thursday, when it rolled out a debit card featuring the likeness of Tubman, a real-life historical figure, engaged in a pose popularized by a fictional, Afrofuturistic superhero movie.

Almost immediately, the company was accused of co-opting a Black historical figure and trying to pander to Black customers. On social media, critics called the card cheesy and exploitative and “unironically tasteless,” as some wondered if the whole thing was an elaborate joke.

But as the company pointed out on Twitter, Tubman is not supposed to be making any sort of reference to “Black Panther” or Wakanda, the fictional, sub-Saharan nation where it takes place. Rather, she is saying the word for “love” in American Sign Language (ASL).

Advertising

“She was about love,” Addonis Parker, the Miami artist behind the painting, told The Washington Post. “It took sacrifice and love for her to do everything she’s done.”

While OneUnited, the nation’s largest Black-owned bank, sought to clarify that the card was meant to be an unapologetic show of Blackness, that didn’t seem to make much of a difference to many on social media. The last place Tubman belongs, they said, is on a piece of plastic used for financial transactions.

OneUnited Bank has its roots in four financial institutions founded in the 1960s, when Black people were largely shut of out of mainstream institutions, its president, Teri Williams, told The Post on Thursday.

In 2015, following a hefty bailout package during the financial crisis, the bank tried to re-brand itself. No longer was it a financial institution that happened to have Black owners and customers. It was a Black bank that was unapologetic about its identity.

That started with hiring Parker to work with Miami youth on a mural outside its branch in Liberty City, a heavily Black part of town, and using some of the painter’s artwork on their credit cards. There was one of a woman in an Afro holding up her fist, and another of a young Black boy flashing a peace sign and wearing a hoodie, in reference to Trayvon Martin.

As debate began swirling a few years ago over the possibility of putting Tubman on the $20 bill, Parker came to Williams with an idea: Why not put her on a debit card too?

Advertising

It made sense, Williams said, because “the card is really an extension of our whole way in which we’ve been communicating to our community: Black money matters and social justice is intertwined with building economic wealth.”

Once the possibility of Tubman on U.S. currency was blocked at the federal level, they decided to move ahead with her on a debit card.

While crafting the design, Parker said he meant to include Tubman saying the word “love” in American Sign Language. While that sign is generally interpreted by crossing your arms and balling your fists directly in front of your chest, Tubman needed to fit on a space the size of a debit card. So he moved her arms up a bit.

Indeed, he pointed out Thursday, the Wakanda salute comes from the same word. As director Ryan Coogler said in the director’s commentary to “Black Panther,” the motion was also inspired by the ASL word for “love” or “hug” as well as West African sculptures and images of pharaohs.

When OneNation launched the debit card Thursday morning, though, the internet did not hold back: Some assumed the company had not even considered hiring Black people to help brainstorm the debit card concept. Not to mention, they said, Tubman looked far too ashy in the painting.

“Who thought this was a good idea?” one person asked.

“Is it April Fools’ Day already?” said another.

“Take me now lord,” added a third.

It wasn’t long before OneUnited jumped into the fray to clear things up.

“Harriet Tubman is the ultimate symbol of love — love that causes you to sacrifice everything, including your own life,” the bank said on Twitter. “The gesture is the sign language symbol for love. It’s so important that we love ourselves.”

Never mind, as some pointed out, that Tubman did not die on the Underground Railroad.

There was also the fact that this was still a debit card made by a bank.

Williams said that she supported the idea of Tubman on a debit card — or on any form of currency — because it can change perceptions about the association between Black people and finance.

“When people think of banking and they think of money, they don’t think of Black people,” she said. “When people think of money, they have a view that we as a community are not responsible, or we as a community don’t have resources.”

Yet while the idea of Tubman on a $20 was not universally accepted, it also seems to have been more palatable for most than her likeness being used by a financial institution with a bottom line.

Writing on Jezebel.com, Justice Namaste called the Tubman debit card another example of “companies [that] pull some truly wild and cringeworthy PR stunts.” This time, she said, the only difference was that it was thinly veiled under the guise of Black empowerment.

“For Black people across the United States, Black History Month is a time of celebration, where we honor our history, our culture, and our centuries of resistance,” she wrote said. “Next year we’d prefer reparations.”

This story was originally published at washingtonpost.com. Read it here.