Labor Unions Need All the Help They Can Get

The House just passed a bill making it easier for workers to organize. It doesn’t go far enough.

by Noah SmithThe House of Representatives just passed an interesting bill dealing with organized labor. Known as the Protect the Right to Organize Act, the bill would ban states from enacting so-called right-to-work laws. It would make it illegal for employers to permanently replace striking workers, and it would impose a nationwide rule similar to California’s recent AB-5 legislation, reclassifying many independent contractors such as Uber drivers as regular employees. It also would impose various penalties on employers that violated labor laws or retaliated against unions. The bill is unlikely to pass a Republican-controlled Senate, but this could change after the next election.

Unions have historically been a pillar of the middle class, and strengthening them could help reduce wage inequality, increase labor’s share of national income and provide many low-wage workers with much-needed stability. So the PRO Act is a welcome development. But its focus might be too narrow to make much difference.

A ban on right-to-work laws has long been a goal of the labor movement. These somewhat misnamed laws don’t actually protect the right to work; instead, they prohibit unionized workplaces from requiring non-unionized workers to pay union dues, creating a free-rider problem. These laws now are on the books in 27 states, and they’ve proved difficult to expunge, even when Democrats are in power.

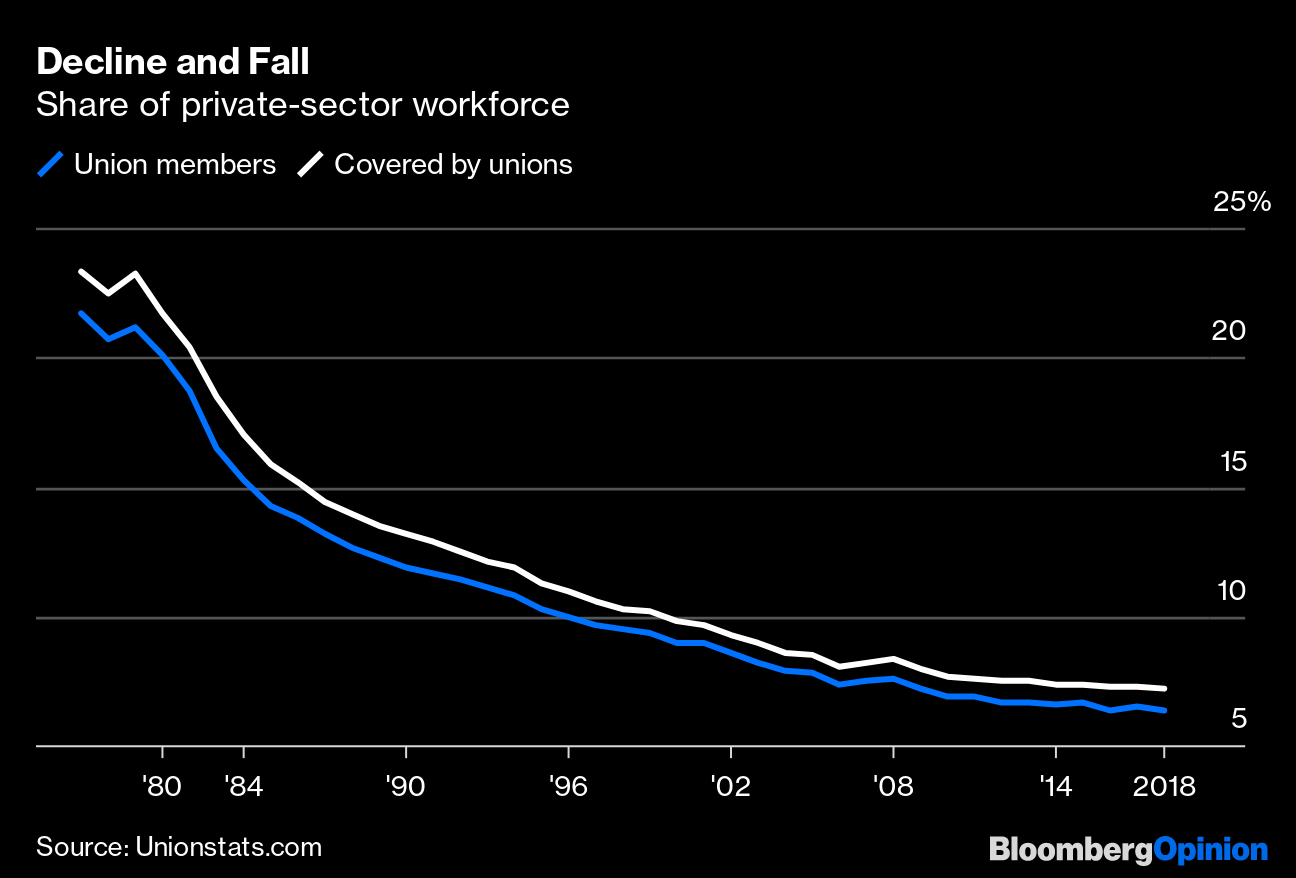

Allowing unions to gather dues from workers who aren’t in the union would give them more financial resources, which could be spent on unionization drives. But this may not do much to halt the decline in union membership. After all, many states don’t have these laws, and private-sector unionization has still fallen precipitously:

In states without right-to-work laws, unionization is about twice as high as in states with the laws -- but that’s still only about 14% of the workforce, including public-sector unions. And some of that difference may not be due to the laws, but because those states are simply more likely to tolerate unions in the first place. For example, New York has higher productivity than Tennessee, meaning that it might be more capable of supporting organized labor.

So ending right-to-work laws would give unions a boost, but it would likely be a modest one. The ban on permanent replacement of striking workers might have more of an effect. It would reduce the risk to workers of going on strike, which would make unionization a more attractive prospect. Stricter penalties on companies that try to skirt labor laws would also help on the margin.

But none of these changes would address the real problem with the U.S. labor system, which is the way unions are allowed to organize. Under the current system, established in the New Deal in the 1930s, each workplace votes on whether to form a union. That means that unionized workplaces, if they successfully bargain for higher wages and benefits, can place themselves at a competitive disadvantage relative to nonunion shops. Even employers who would be willing to share more of their profits with their workers will try hard to bust a union if they fear it would mean losing business to rivals. And unions are probably less willing to bargain in the first place if their employer’s higher wages wouldn’t be matched by competitors.

The solution is to allow collective bargaining at the level of an entire industry -- a policy known as sectoral bargaining. For example, instead of each fast-food restaurant being forced to choose whether to be a union shop, all the fast-food restaurants in a given city would strike the same bargain at the same time. That would end the competitive disparity that now does so much to undermine unionization.

Sectoral bargaining could be done several ways. One is to require all establishments in a given industry in a given area to be represented by one union. Either all workers would have to be in the union, or the union would be allowed to bargain on behalf of non-members -- a system that is used to great effect in countries such as France. An alternative is to give multiple labor organizations a seat at the table in each sector, allowing them to compete for representation by offering services to their members. A third option is to set wages in a sector with a government-appointed wage board instead of union-management negotiations.

Sectoral bargaining would require a major rewrite of U.S. labor law. But as long as Congress is passing big labor legislation, it might as well be ambitious. Getting rid of right-to-work laws and making it easier to strike would be welcome changes, but only a partial corrective to unions’ long decline. We need to think even bigger.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Noah Smith at nsmith150@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net