Here's What People Thought of YouTube When It First Launched in the Mid-2000s

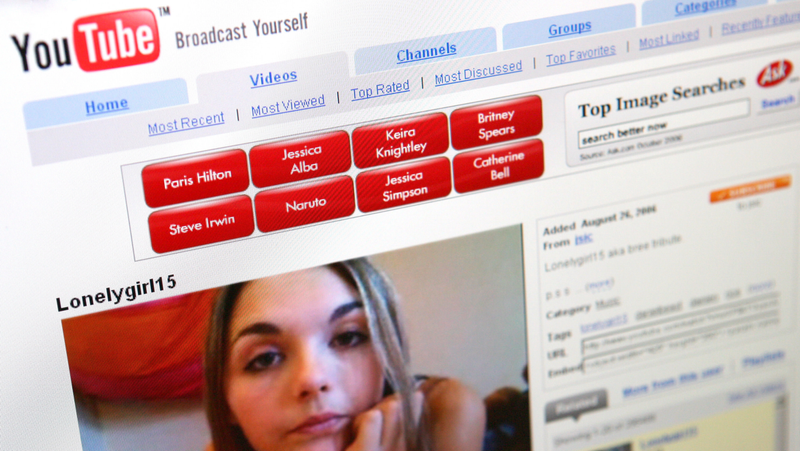

by Matt NovakWhen YouTube first launched 15 years ago, a lot of people weren’t sure what to make of it. Anyone can upload a video to this service? Why do I want to hear what some obnoxious teenager has to say from their bedroom?

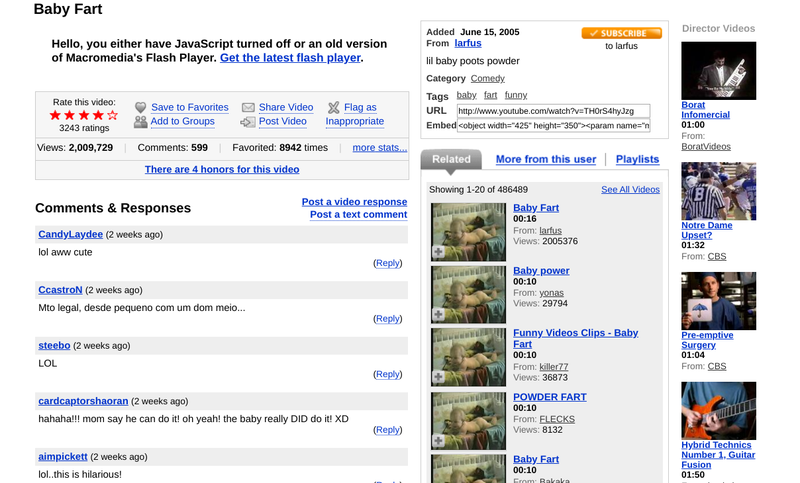

YouTube was much more than that, of course. Most of the site’s most popular videos in the early days were taken from traditional media channels like Comedy Central and shared without permission from the copyright holders. But it also opened up doors for plenty of people who saw an opportunity to push the limits of a new medium.

We’ve already looked at what people thought of Amazon when it launched in the mid-1990s and iTunes when it launched in 2001. But what did people think of YouTube in its early years, after the domain was purchased on February 14, 2005, and the website was developed shortly after that?

YouTube’s birth in 2005

Founded by Steve Chen and Chad Hurley, YouTube was an almost immediate success. And some of that success is owed to the young people who created content for the site long before they could make money doing it. But even some of the earliest amateur filmmakers on YouTube didn’t put their content there themselves.

David Lehre, a 10th grader from Michigan, uploaded his short film “MySpace: The Movie” to his own website on January 28, 2005. Someone he didn’t know downloaded the video and uploaded it to YouTube just a few days later, where it racked up six million views in just a few weeks. By the end of February, Lehre uploaded it himself. (As of this writing, the “official” video has just over one million views.) On February 26, 2005, a story from the Associated Press ran in newspapers around the country, explaining this new platform and Lehre’s shot to semi-celebrity. The AP story explained that Lehre’s video was being played on Current TV (a failed liberal cable TV channel started by Al Gore) and that Lehre had gotten an offer to develop something at MTV’s college-targeted channel, MTVU. The point seemed to be that anyone could make it big in an age of abundant DIY video.

There were actually a number of different video-sharing sites in 2005, including Clipshack, VSocial, Grouper, Metacafe, Revver, and OurMedia. Even Vimeo, launched in November of 2004, was already on the scene when YouTube arrived. But YouTube stole the show in 2005 and Mashable hailed the “Flickr of video” as the likely winner.

From Mashable on December 26, 2005:

YouTube is way ahead of many of these [other] services - YouTube videos are appearing on blogs and websites all over the place. OurMedia is also excellent, but it’s a non-profit and I’m more interested in startups right now. I’m also a fan of Grouper - it’s definitely one to watch.

Now correct me if I’m wrong, but the only video sharing service with a clear business model right now is Revver - they’re putting ads in videos and splitting the revenue with the content creator. Even this seems like a difficult thing to pull off - can they earn enough from the ads to pay for their bandwidth and reward the content creators? I’m not sure - but I’m keen to find out.

December of 2005 was a big month for YouTube, with the debut of “Lazy Sunday,” a goofy rap video by Andy Samberg and Chris Parnell for Saturday Night Live about going to see the then-popular movie The Chronicles of Narnia. When the L.A. Times wrote about “Lazy Sunday,” print subscribers even got a URL that they would presumably have to type out if they wanted to see the video on YouTube.

People wanted to share “Lazy Sunday” on YouTube and NBC—which owned the video and didn’t want anyone watching it on anything but approved channels like NBC.com—kicked up a fuss for months. Every time someone would upload the video again, YouTube had to take it down. This, of course, was before YouTube developed the technology for automatically recognizing copyrighted content through a program called Content ID, eventually introduced in 2007.

From the New York Times on February 20, 2006:

Fans immediately began putting copies of the video online. On one free video-sharing site, YouTube (www.youtube.com), it was watched five million times in a few days. NBC soon made the video available as a free download from the Apple iTunes Music Store.

Julie Supan, senior director of marketing for YouTube, said she contacted NBC Universal about working out a deal to feature NBC clips, including “Lazy Sunday,” on the site. NBC Universal responded early this month with a notice asking YouTube to remove about 500 clips of NBC material from its site or face legal action under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. YouTube complied last week. “Lazy Sunday” is still available for free viewing on NBC’s Web site, and costs $1.99 on iTunes.

“Lazy Sunday” managed to break SNL out of a cold snap of irrelevancy, but big media companies still wanted exclusive control of their content. And the issue would create a lot of worries for people with a vested interest in online media.

The promise of web 2.0 and the threat of lawsuits

By the first half of 2006, YouTube was solidly identified as part of the “Web 2.0" revolution which started just a few years earlier. While Web version 1 may have been the invention of the consumer internet in the early ‘90s until the Dotcom Crash of 2000, the second version of the web was to be much more interactive. Sites like MySpace (launched in August of 2003), Flickr (launched in February of 2004) and YouTube were going to revolutionize the way that average people interacted online. Wikipedia, founded in January of 2001, was arguably part of that same post-2000 user-created revolution, albeit a couple of years early to the game.

The first version of the web was static and had much more limited opportunities for interaction. Sure, there were chatrooms, but sharing things like videos and photos was incredibly difficult. And making your own website was a chore for people with plenty of time and knowledge. Web 2.0 changed all that by giving people the tools to share things without having to know how to code their own sites. Sure, you could make your own Angelfire page in the late 90s, but how was anyone going to find it, let alone care?

But some people, like tech commentator Paul Boutin at Slate, didn’t believe that Web 2.0 would live up to the hype and that the next bubble could be just over the horizon.

From Slate on March 29, 2006:

The salesmanship that surrounds Web 2.0 is the key to understanding what the phrase really means. The new generation of dot-com entrepreneurs confers 2.0 status upon everything because they missed out on the boom times of Web 1.0. They want a new round of buzz and bling for themselves, and who can blame them? Crawling your way up the ladder at eBay is the loser track. A winner creates eBay 2.0. And they’re right to be stoked about the Web again. Investors are emerging from hibernation, tech jobs are coming back from Bangalore, and online services have evolved to the point where Wired’s most preposterous scenarios from 10 years ago now look mundane.

Fundamentally, YouTube was built on content piracy, but that didn’t scare away big money. Quite the contrary. On October 9, 2006, Google announced that it was purchasing YouTube for $1.65 billion in stock.

Google had its own video service at the time, known as Google Video, which eventually folded. But plenty of people thought Google was crazy for buying up a video company that relied so heavily on pirated content. YouTube was getting sued left and right, and people like billionaire Mark Cuban wondered if the big media companies might even sue individual YouTube users.

“I think there will be supoenas [sic] to get the names of Youtube and Google Video users. Lots of them as those copyright owners not part of the gravy train go after both Google and their users for infringement,” Cuban wrote on October 9, 2006.

That didn’t happen, of course. But it wasn’t a bizarre idea at the time. YouTube may have been the best place for “light saber fights and karaoke lessons,” as the L.A. Times described it in 2006, but it was also the best place for pirated clips of Comedy Central’s Crank Yankers and Mitch Hedberg stand-up comedy sets.

In 2007, YouTube started to get serious about monetizing its content and introduced all kinds of different strategies, like overlay ads, and was striking more deals with traditional media companies to share revenue. That gave financial-focused commentators more confidence that Google was on the right track and wouldn’t be sued into oblivion. And that was also the year it introduced Content ID. All it took was a $1 billion lawsuit from a company like Viacom.

2008 becomes the YouTube election

Virginia Heffernan wrote an article in the November 14, 2008 edition of the New York Times magazine, published shortly after Barack Obama won his first term in office and became the first black president of the United States.

In a YouTube video on January 16, 2007, then-Senator Barack Obama announced that he was forming a committee to explore running for president. The video, “Barack Obama: My Plans for 2008,” can still be viewed on the video platform.

As Heffernan notes, 7 of the 16 people who tried to become president in 2008 announced their candidacy on YouTube. Barack Obama uploaded 1,800 videos to his YouTube channel during the campaign and had over 110 million views by Election Day.

From the New York Times Magazine:

During the presidential election, YouTube turned from a hectic mosaic of weird video clips to a first-stop source for political everything. Every gotcha moment, spoof, pundit’s musing, TV clip, campaign speech, formal ad and handmade polemic cropped up there. Star posters like Brave New Films, Barely Political and Talking Points Memo TV emerged; they cranked out parody and propaganda much faster than the campaigns themselves. Was YouTube just a new place to envision an election that would have gone the same way without it? Or does the unpredictable new form of online video carry its own ideology — a new message to go with a new medium?

Did YouTube help Obama win? Probably, in some small part. But Heffernan was still extremely skeptical. Heffernan concluded that while YouTube might be interesting, it’s not a serious player.

The story of YouTube, so far, is not necessarily the story of the business of the future; it’s too strange a place and too uncertain a profit model to inspire copycats. As a minicivilization, though — with heroes and villains and mores and bylaws — YouTube is a fascinating place.

YouTube as the future of democracy in 2009

By 2009, people already had lofty techno-utopian goals for the platform, envisioning it as a liberating and “democratic” force for good.

A 2009 paper from UCLA’s Journal of Education and Information Studies titled, “The Future of YouTube: Critical Reflections on YouTube Users’ Discussion Over Its Future” took a look at the video platform and saw wonderful things ahead.

From the 2009 journal article:

[YouTube’s] contribution to the democratization of media spectacles further provides an innovative perspective on the Internet’s potential for direct democracy with broader cultural, educational, and sociopolitical implications. In other words, [YouTube] brings individuals opportunities to become active participants in the construction of alternative culture and to promote values of human agency, grassroots democracy, and social reconstruction.

The paper went even further, arguing that people who created and consumed YouTube videos were working on building a space where people could respect each other and work on a society where people are equal.

In terms of the forms of [YouTube] uses, [YouTubers] have the potential of the democratic public sphere in mind and, to some extent, they are developing a more egalitarian public sphere.

I’ve got some really bad news from the future for the author of that paper.

The rest of the garbage

YouTube grew and grew throughout the 2010s, becoming the most popular social media platform with teens in 2018, according to the Pew Research Center. While 51 percent of teens (aged 13 to 18) said they used Facebook in Pew’s 2018 survey, a whopping 85 percent used YouTube.

The platform has been shaping young minds throughout the 2010s, often for the worse. YouTube is filled with PTSD-inducing trauma for both its consumers and its moderators. And far right media commentators have gamed the system to radicalize young people who might otherwise grow up to be decent.

Just take a glance at some recent Gizmodo headlines about YouTube:

- How YouTube Profits From Climate Denial and Disinformation

- Wildly Popular Kid YouTube Channel Accused of Deceptively Promoting Products to Millions of Children

- YouTube’s Content Moderators Are Asked to Contractually Acknowledge the Job Can Give Them PTSD

- YouTube’s Nightmare Algorithm Exploited Children by Recommending Pedophiles Watch Home Movies of Kids

What ever happened to that 10th grader in Michigan who made that video about MySpace? His IMDB profile explains that he’s an “Internet video pioneer who has racked up over 400+ Million video views worldwide over the past decade.” But aside from a role in the 2007 Ashton Kutcher comedy Epic Movie, his credits haven’t gone viral since.

With the hindsight of 15 years, we can say that fleeting social media fame isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.