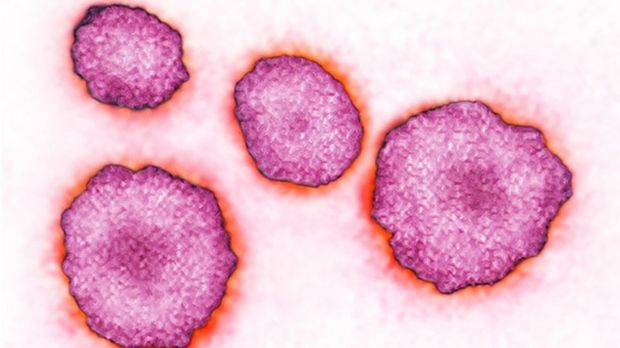

Mumps: Why adults might still need the MMR jab

Health experts are warning young adults are at risk of developing mumps because many of their age group missed out on getting two doses of the MMR jab as children.

Latest figures show cases of mumps in England have reached their highest level in a decade.

So why is mumps a risk, and how effective is the MMR vaccination?

Is mumps risky for adults?

It can be.

The viral infection used to be very common in children before the MMR jab was introduced in the UK in 1988.

It usually causes painful swelling in the glands at the side of the face, plus joint pains, fever and tiredness.

Most recover without treatment. But it can cause complications including:

- Swollen testicles - this affects one in four men who get mumps after puberty. An estimated one in 10 of them experience a drop in their sperm count, though this is rarely enough to cause infertility.

- Viral meningitis - this occurs in about one in seven cases of mumps. It is less serious than bacterial meningitis and usually passes in a couple of weeks. However, around one in 1,000 people who develop viral meningitis develop encephalitis, a potentially fatal infection of the brain

- Pancreatitis - about one in 20 cases leads to short-term inflammation of the pancreas (acute pancreatitis)

- Hearing - one in 20 experiences some temporary hearing loss. Permanent hearing loss is extremely rare, occurring in around one in 20,000 cases of mumps.

Source: NHS UK

How many cases are there?

In England, there were 5,042 in 2019 - four times the number in 2018.

Public Health Wales identified 2,695 potential cases of mumps in 2019 - up from 519 in 2018.

Scotland records its figures on a slightly different timescale, but Health Protection Scotland says that up until the end of September there were 554 confirmed cases, compared with 218 in 2018.

Northern Ireland also had a rise in cases last year, with the Public Health Agency (PHA) recording 198 cases between January and May 2019, compared with 66 in the whole of 2018.

What is the MMR vaccine and who can have it?

Millions of children have been vaccinated against mumps - as well as measles and rubella (also known as German measles) - since the MMR vaccine was introduced in the UK more than 30 years ago.

The conditions are all highly infectious, with potentially serious complications, and can make babies, children and adults very unwell.

Babies get the first dose at 12-13 months and the second booster injection before starting school, usually at around three-to-four years old.

Two doses are required to be fully protected.

Any adults who need the MMR should contact their GP to arrange the vaccination.

How effective is the vaccine?

It is safe and very effective.

Around 99% of people will be protected against measles and rubella after two doses of MMR.

Protection against mumps is a little lower - around 88%.

If people have only one dose of the vaccine, protection will be even less, increasing the risk of the illnesses spreading.

Before the MMR vaccine was introduced in 1988, huge numbers of children got mumps and there was an average of five deaths a year, usually from brain complications.

What are take-up rates like?

The percentage of children receiving both doses of the MMR jab by their fifth birthday has fallen over the last four years to 86.4% in England.

This is below the 95% target needed to achieve "herd immunity", to ensure the illnesses don't circulate freely.

Scotland and Northern Ireland are seeing better vaccination rates, but Wales is not.

Take-up rates have been declining in many other countries too.

That has meant that, as well as the rise in mumps, measles cases increased to nearly 1,000 in the UK in 2018 - double the number in 2016.

Health experts warn that children are being put at risk of the devastating impact of measles, mumps and rubella by failing to have the vaccine.

What's the reason for falling rates?

In 1998, a study by former doctor Andrew Wakefield incorrectly linked the MMR vaccine to autism. The research is now completely discredited.

But it had an impact on the coverage of the vaccine, which dropped to about 80% in the late 1990s and a low of 79% in 2003.

After that, vaccine rates started to recover but anti-vaccine myths on social media have since been blamed for having a negative impact on parents' confidence in the jab.

The UK's chief medical officer has previously criticised the anti-vaccine movement and urged parents to ignore "social media fake news".