Bloomberg Misleads on Stop-And-Frisk

by Robert FarleyDemocratic presidential candidate Mike Bloomberg misleadingly stated that he “cut” the police practice of stop-and-frisk — a policy that he “inherited” — by “95%” by the time he left office as mayor of New York. There were nearly twice as many stops in his last year as mayor compared with the year before he took office.

It’s true that the number of recorded stops declined steadily over the last two years of Bloomberg’s 12 years in office. But Bloomberg’s statistic ignores the dramatic rise in such stops in earlier years under his watch. He also fails to mention that the decline in later years came amid public backlash about the policy and mounting pressure from a class-action lawsuit.

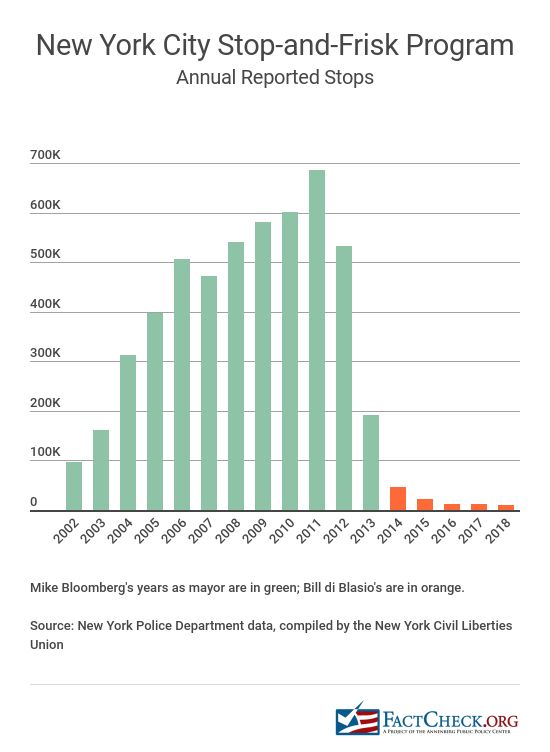

In Bloomberg’s first 10 years in office, the number of stop-and-frisk actions increased nearly 600% from what he “inherited,” reaching a peak of nearly 686,000 stops in 2011. There were about 192,000 documented stops in 2013.

Bloomberg gets to his figure of a 95% cut by cherry-picking the quarterly high point of 203,500 stops in the first quarter of 2012 and comparing that with the 12,485 stops in the last quarter of 2013 — a decline that would not have been possible without the numbers ballooning earlier in Bloomberg’s tenure.

Bloomberg continued to defend the stop-and-frisk practice throughout his term as mayor — and after — maintaining that the policy led to a decrease in crime, a justification he now acknowledges was wrong.

Days before announcing his candidacy for president in November, Bloomberg said that he “should have acted sooner, and acted faster to cut the stops,” and he apologized for not doing that.

Aspen Institute Speech

The issue of Bloomberg’s controversial use of stop-and-frisk as mayor of New York resurfaced in the national media after journalist Benjamin Dixon posted an audio clip of Bloomberg defending the stop-and-frisk policy during an address in 2015 at the Aspen Institute. Bloomberg contended the policy was responsible for lower murder rates. (Bloomberg now acknowledges that “crime continued to come down as we reduced stops.”)

Bloomberg, Feb. 5, 2015: Ninety-five percent of murders, murderers and murder victims, fit one M.O. You can just take a description, Xerox it, and pass it out to all the cops. They are male minorities, 16 to 25. That’s true in New York, that’s true in virtually every city (inaudible). And that’s where the real crime is. You’ve got to get the guns out of the hands of people that are getting killed. … You want to spend the money on a lot of cops in the streets. Put those cops where the crime is, which means in minority neighborhoods. So, one of the unintended consequences is people say, “Oh my God, you are arresting kids for marijuana that are all minorities.” Yes, that’s true. Why? Because we put all the cops in minority neighborhoods. Yes, that’s true. Why do we do it? Because that’s where all the crime is. … And the way you get the guns out of the kids’ hands is to throw them up against the wall and frisk them. And then they start, “Oh, I don’t want to get caught,” so they don’t bring the gun. They still have a gun, but they leave it at home.

(The audio posted by Dixon edited out some of Bloomberg’s comments. You can hear full Bloomberg’s answer here.)

Trump, who has a long history of supporting stop-and-frisk policies, tweeted (and then deleted) a link to Dixon’s tweet, along with his own commentary, “WOW, BLOOMBERG IS A TOTAL RACIST!”

Responding to Trump’s tweet, Bloomberg issued a statement saying, in part, “I inherited the police practice of stop-and-frisk, and as part of our effort to stop gun violence it was overused. By the time I left office, I cut it back by 95%, but I should’ve done it faster and sooner. I regret that and I have apologized — and I have taken responsibility for taking too long to understand the impact it had on Black and Latino communities.”

The Rise and Fall of Stops

It’s true, as Bloomberg said, that he inherited the controversial stop-and-frisk policy, a get-tough-on-crime tactic of stopping people for suspicious activity that was begun under former Mayor Rudy Giuliani. According to data revealed by the state attorney general’s office as part of an investigation into the city’s policy, there were a little fewer than 100,000 recorded stops in 2001, the year before Bloomberg took office.

In the ensuing years under Bloomberg, the number of reported stops increased dramatically year after year, peaking at nearly 686,000 in 2011, based on New York Police Department quarterly reports compiled by the ACLU of New York. From then on, the number of recorded stops began a steady decline. There were nearly 192,000 stops in 2013, Bloomberg’s final year as mayor. But even in that year, the data show steady declines in each quarter.

As we explained, Bloomberg is using quarterly numbers, comparing the first quarter of 2012 with the fourth quarter of 2013, which shows a 94% decrease.

Under Bloomberg’s successor, Bill di Blasio — who ran for mayor on a platform opposing the stop-and-frisk policy — the number of such stops continued to decline dramatically, to nearly 46,000 in di Blasio’s first year in office in 2014 and about 11,000 in 2018.

Bloomberg has attributed the decline that started in 2012 to better training, although he consistently defended the stop-and-frisk program at the time and insisted it reduced violent crime. A day after a federal judge granted class-action status to a lawsuit brought by people who had been stopped, the police department in May 2012 announced new training and supervision designed to address concerns about racial profiling in the application of stop-and-frisk.

The decline also came amid growing public outrage about the stop-and-frisk program. In April 2013, a survey conducted by Quinnipiac University found 51% of New York City voters disapproved of the stop-and-frisk policy and two-thirds supported a plan to create an inspector general to monitor the police department, a proposal that Bloomberg opposed.

Perhaps the biggest blow to the stop-and-frisk program came on Aug. 12, 2013, when U.S. District Court Judge Shira A. Scheindlin ruled that the city police department violated the U.S. Constitution in the way that it carried out its stop-and-frisk program, calling it “a form of racial profiling” of young black and Hispanic men. In her opinion, Scheindlin wrote that she was “not ordering an end to the practice of stop and frisk” and that the practice could continue if the city complied with court-ordered remedies to make sure that the program did not violate the Constitution.

The police union and Bloomberg aggressively opposed the lawsuit. In a press conference on the day of the ruling, Bloomberg called the “stop-question-frisk” policy “a vital deterrent” and credited the policy with playing an important part in helping to make New York City “the safest big city in America,” and for leading to “fewer guns, fewer shootings and fewer homicides.” Bloomberg attacked the judge as biased and vowed to appeal her ruling. (Di Blasio later declined to pursue the appeal.)

Less than two weeks later, New York’s City Council passed two bills designed to provide oversight of the police department’s stop-and-frisk policy — one to create an independent inspector general to monitor the police department and another to make it easier for people to sue the police department over racial profiling. Bloomberg vetoed both bills, but the council overrode those vetoes.

Did the Policy Work?

Even after he left office, Bloomberg continued to defend the stop-and-frisk policy. As recently as January 2019, Bloomberg insisted the policy had led to a decline in the city’s murder rate, though the number of murders continued to dip even as the stop-and-frisk policy was phased out.

In a fact-check article about whether stop-and-frisk reduced crime in New York City, John MacDonald, a professor of criminology and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote that academic research concluded “NYPD’s deployment of extra police to high crime neighborhoods contributed far more to the crime reduction than the use of stop, question, and frisk.”

“The additional use of stop, question, and frisk made almost no difference,” MacDonald wrote. “The stops only had a detectable impact on crime when the stops were based on probable cause, and these kinds of stops were very rare.”

In a speech on Nov. 17, just days before announcing his candidacy, Bloomberg acknowledged that “far too many innocent people were being stopped,” that it eroded trust from the black and Latino communities and that “crime did not go back up” when the policy was scaled. He concluded, “We could and should have acted sooner, and acted faster to cut the stops. I wish we had. And I’m sorry that we didn’t.”

Bloomberg, Nov. 17: Over time, I’ve come to understand something that I long struggled to admit to myself. I got something important wrong. I got something important really wrong. I didn’t understand that back then the full impact that stops were having on the black and Latino communities. I was totally focused on saving lives, but as we know, good intentions aren’t good enough. Now, hindsight is 20/20, but as crime continued to come down as we reduced stops, and has continued to come down during the next administration, to his credit, I now see that we could and should have acted sooner, and acted faster to cut the stops. I wish we had. And I’m sorry that we didn’t.

Bloomberg said that “in 2012, in my third term, we began putting more safeguards in place. And we began scaling back the numbers of stops.” The numbers corroborate that, but Darius Charney, a lawyer for the plaintiffs in the class-action case about the stop-and-frisk policy, said it is more likely the decline in documented stops came because of a shift in the public tide against the policy and the fact that it was facing legal challenge in the courts and push-back from the City Council.

Bloomberg may portray the change as coming as a result of realizing the error of his ways, Charney said, but that “doesn’t seem consistent with the way he was behaving publicly.” Bloomberg, he noted, was “aggressive and defiant” in defending the policy. He fought the class-action lawsuit and sought to appeal the ruling. He vetoed City Council efforts to rein in the program. And he made numerous statements in support of stop-and-frisk.

No matter the reason for the decline in stops, though, Bloomberg’s explanation that he “inherited the police practice of stop-and-frisk” and “cut it back by 95%,” may leave the mistaken impression that he cut the program by that amount from what he inherited. In fact, the practice greatly expanded under his watch — and with his encouragement — and then contracted from that height during his last two years in office.

Trump’s Position

In addition to Trump’s since-deleted tweet forwarding the audio clip and branding Bloomberg a “racist,” Trump also retweeted a post from Van Jones, a CNN commentator and former adviser to President Barack Obama, saying on CNN, “I think Bloomberg has a problem because of what he did. You know, stop-and-frisk … it was a horror show to be black or Latino in New York City for years, because you were constantly being stopped and harassed by the police whether you were doing anything wrong or not. And Bloomberg defended it until 20 minutes ago.”

Readers can make of Bloomberg’s comments what they will, but Trump has also long expressed support for stop-and-frisk policies. As recently as Oct. 8, 2018, Trump recommended that Chicago “strongly consider stop-and-frisk. It works and it was meant for problems like Chicago. It was meant for it.”

In a radio interview with Geraldo Rivera on Feb. 13 (starting around the 22:10 mark), Trump drew a distinction between the way the policy was applied by Giuliani and Bloomberg. According to Trump, Giuliani used the practice “sparingly,” “gingerly” and “really brilliantly.” Bloomberg, he said, “came in and he multiplied it times 10.”

“If you were a black person walking down the street, you were going to be stopped and frisked under Bloomberg,” Trump said. “And that’s why they had a revolution in New York, because of what he did.”

“He took Rudy’s stop and frisk, which was done very gingerly, very smartly, you know, a very smart job, and he made it so vicious and so violent,” Trump said. “And honestly, if you were a black person, you’d be stopped two, three times a day.”

But when Bloomberg was in office, Trump’s tweets about stop-and-frisk don’t reflect reservations about how the mayor was applying the policy. In July and August 2013, around the time of the class-action lawsuit ruling, Trump tweeted repeatedly in support of the policy and the way it was being applied, and he warned that ending the policy would be a “disaster” and that crime would rise.

During the first presidential debate between Trump and Hillary Clinton in September 2016, Trump praised stop-and-frisk. He also criticized the judge and her ruling in the New York City case, and he criticized di Blasio for not moving forward with an appeal.

Trump credited the policy — which he said was begun by Giuliani and “continued on by Mayor Bloomberg” — for bringing New York’s crime rate “way down.”

When Clinton noted that crime, including murder, continued to drop, even as di Blasio phased out stop-and-frisk, Trump said Clinton was “wrong.” At the time, we wrote that both were right, because murders went down in di Blasio’s first year in office, but then ticked back up in 2015. In the ensuing two years, however, the number of murders again dropped. The number of murders in New York City in 2017, 2018 and 2019 were all lower than the best year under Bloomberg, and well below the numbers under Giuliani.