England cricket team

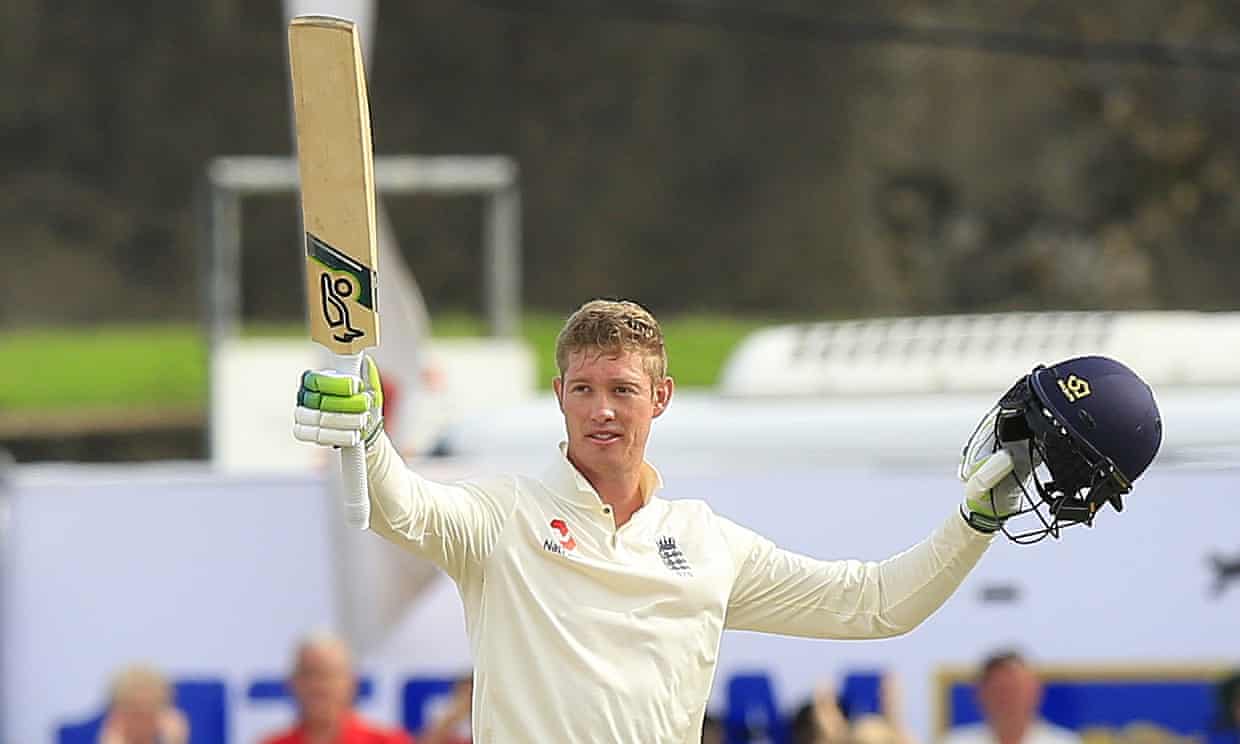

Keaton Jennings: 'I made the pursuit of hundreds my reason for existing'

Recalled to the England Test side the opener has a new-found perspective on cricket which will survive whether he thrives or fails in Sri Lanka next month

by Daniel GallanKeaton Jennings will not be reading this article. That is a departure for the 27-year-old, recently recalled to England’s Test squad and who used to spend late nights poring over every piece that mentioned his name. He would also scrawl through his Twitter feed fretting over the opinions of strangers. Deleting the app from his phone on multiple occasions was the only way he could wrench himself away from the noise.

“I was in a dark space,” Jennings says from Tasmania, Australia, where he is with the England Lions. “My head was clouded. I was so worried about what others thought of me and my technique. It was like living in a fish bowl with the whole world looking in. Even when I was alone I felt eyes on me. It got so bad that I’d second guess even the most mundane things like what coffee I ordered in the morning. I was a mess inside.”

The problems began during the home summer of 2017 when South Africa’s Morne Morkel and Vernon Philander rendered Jennings a walking wicket. In four Tests he scored 127 runs at 15.87 and was dropped ahead of the end of year Ashes series.

A lack of options at the top of the order meant Jennings was reinstated for the arrival of India. But another poor series riddled with the same technical flaws outside his off stump saw Jennings average 18.11 with a highest score of 28. Ordinarily that would have been that, but a Test ton on debut in Mumbai in 2016 planted the idea that Jennings’s game was tailor-made for the subcontinent. An unbeaten 146 in Galle littered with sweeps on both sides of the wicket saw this notion bloom. A meagre return in the West Indies established the theory as dogma.

After 17 Tests, Jennings averages 49.75 against spin and 16.65 against pace. Both his hundreds have been registered in Asia where he averages 44.44 in five matches. At home and in the Caribbean, he has a high score of just 48 from 12 Tests and an average of 17.31.

After missing out on the seaming decks in New Zealand and South Africa, Jennings is back for the two-match series on the spin friendly strips of Sri Lanka. Former England captain Nasser Hussain has labelled his selection as short-termism, but national selector, Ed Smith, referenced the unique challenges of batting in Asia as justification for his inclusion. So, how does the man in the middle of the maelstrom feel?

“Honestly, I’m not fussed one way or the other,” Jennings replies. “If people want to pigeonhole me as a sub-continent specialist that’s fine by me. I developed my game in Durham and now play in Lancashire. Those are hardly dust bowls. I’m spending less time worrying about what others think. This is my job and I want to perform but ultimately it’s a game. I’ve filled my time with other things and as a result I’m enjoying my cricket more than I ever have. I can’t wait to be involved with the team again.”

Jennings uses the word “perspective” on several occasions during our conversation. After working closely with his father Ray – the former wicketkeeper and coach of South Africa – and his uncle Kenneth – a sports psychologist – the younger Jennings has dedicated his life to other pursuits. In June he will graduate with a BA in business management and accounting from the Open University and he has applied for an MBA starting in September.

“It’s hard to worry about that poor net session or what the newspapers are saying about you when you’re nose deep in Porter’s Six Forces model,” he says. “I have no choice but to leave the baggage on the field.”

That is not to say Jennings hasn’t been hard at work fine-tuning his game. He has lost count of the amount of hours he has spent with former Lancashire opener Mark Chilton, now an assistant coach at Old Trafford. Weight transfer has been an issue in the past and moving all the way forward, or all the way back, has given Jennings a better awareness of when to leave the ball thanks to improved head positions.

He has also worked on his fitness, training with his brother Dylan who competes on the Ironman circuit in South Africa. “Nothing humbles you more than running with an athlete like that,” Jennings says. “He kicks my arse.”

Jennings cites the “tough love” he received from his family as a reason for his newfound zen. “They smacked me back to where I needed to be. I made the pursuit of hundreds the centre of my universe, my reason for existing. They reminded me that being a good person is the foundation block for everything. It sounds like a cliche but we often forget that in our performance based industry. I could have easily slipped into depression without my family. They kept the light on at the end of the tunnel and I’m so grateful to them for guiding me out the other side.”

Almost certainly this is Jennings’s last chance at the top, even if he doesn’t see it that way. With Zak Crawley and Dominic Sibley impressing in South Africa, and Rory Burns still to return from injury, the state of England’s top order looks in good nick, though the legacies of Alastair Cook and Andrew Strauss loom large.

Not that Jennings is concerned. His self-imposed isolation from the media and his preoccupation with what comes after cricket has given him the freedom to fail without the threat of internal disintegration.

“I look back on the past 18 months as the most important period in my life,” Jennings says. “It was hell at times but I’ve got no complaints. I feel healthy, I feel confident in my game and I feel in control. This growth might not translate into a load of hundreds and an extended run in the team, but for the first time, I’m OK with that.”