Music

'Your instrument is your baby': why musicians dread careless airlines

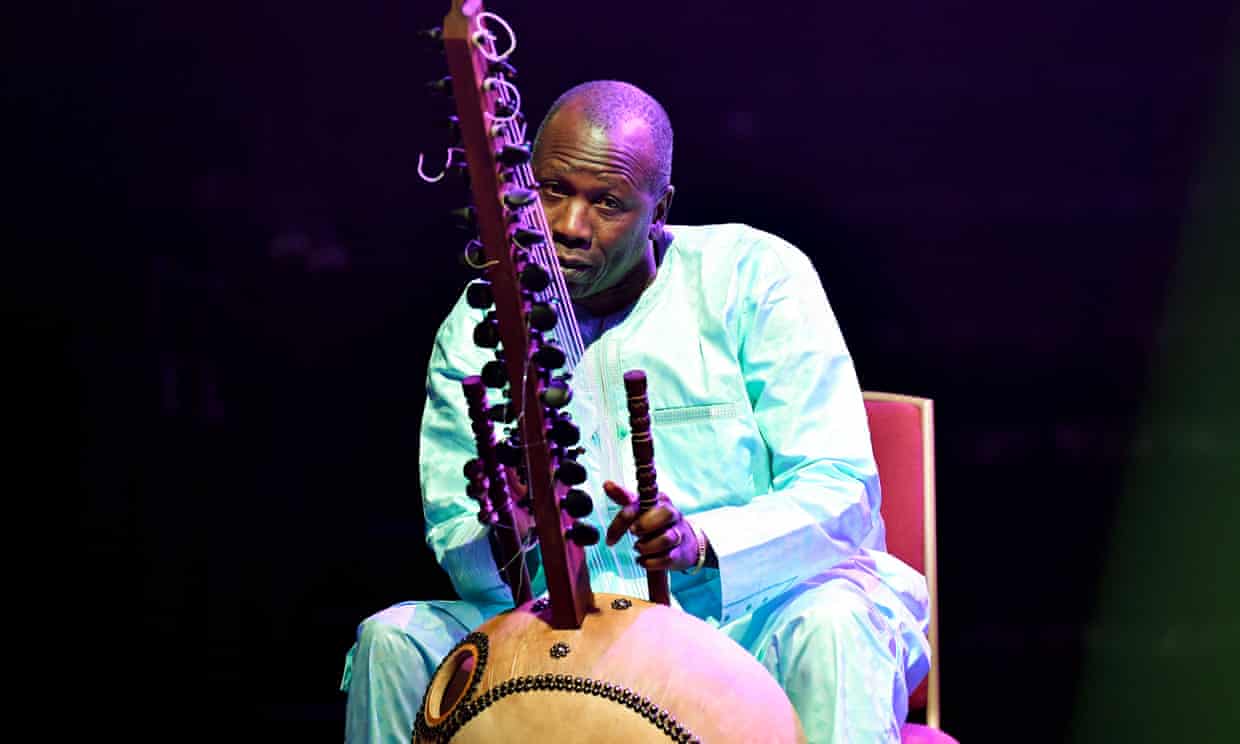

The Malian artist Ballaké Sissoko says US border officials broke his cherished kora. He’s not alone in his plight

by Amanda HolpuchIf Yacouba Diabaté drives too rough over a speed bump on his way to a gig, he automatically apologizes to his instrument, secured in the backseat. The renowned cellist Lynn Harrell can see his cello from his bed and says he is effectively sleeping with it. The virtuoso Wu Man still gets upset when she thinks about the time a flight attendant dropped her pipa, a Chinese lute, in 2013. For musicians, she said, an instrument is like a baby.

Wu’s painful memory is a reminder that the tight bond between a musician and their instrument frequently faces one major threat: the airline industry.

This battle came to the fore last week, when the Malian musician Ballaké Sissoko accused US border officials of breaking his “impossible to replace” kora, a harp-like west African instrument, during a security check before flying from New York to Paris.

The US Transportation Security Administration (TSA) denied it had broken the kora and said security agents hadn’t even inspected Sissoko’s suitcase.

But in an email to the Guardian, Sissoko said: “I cannot believe what they say, because my flight case has been opened, a note from TSA was left inside, so for sure someone has opened it and has disassembled the kora that was in pieces.”

Sissoko was one of several famous musicians who told the Guardian how it is “delicate and difficult” to travel with instruments.

The stakes are high. Not only does a musician have an emotional connection to their instrument, but a break, even if it is repaired to pristine condition, can bring down a valuable instrument’s price. It is also highly likely that a musician traveling with an instrument is on their way to their next gig.

That was Sissoko’s first concern when he found the neck of his kora had been removed and the strings, bridge and amplification system taken apart. He is on tour, playing in London next month, and he could not simply walk into a store to replace a hand-crafted, custom instrument.

Critics said Sissoko shouldn’t have checked the kora or should have put it in a specialized case, but for traditional instruments like his, that is easier said then done.

Wu was traveling to Connecticut to play with the Kronos Quartet in 2013, when a flight attendant dropped her pipa.

“I wanted to cry,” said Wu.

Concert organizers were able to find a replacement instrument for her to borrow but she couldn’t repair her pipa until her next trip to China.

Wu had only checked her pipa once, decades before, and it had broken, so she had never done it again. It is difficult to find a specialized hard case for the pipa, such as the ones people use for guitars, so even bringing it in the cabin as carry-on luggage held risk. Now, Wu often buys the pipa its own seat. “It sometimes looks ridiculous, because the seat doesn’t fit it, but you just want to be safe,” she said.

African instrument damage equivalent to a ‘hate crime’

To be safe, Diabaté has simply stopped doing shows abroad.

Upon returning to the US in 2017, he opened his case to find the new, custom-made kora he had bought on his trip to Burkina Faso and Mali had its neck broken and the strings removed.

Diabaté had bought a hard case for the instrument but was not allowed to bring it in the cabin. He knows how to make koras but said the new one was so difficult to put back together that there was no point.

“It has also kept him from wanting to travel internationally because he doesn’t know what could happen, and because of what happened he doesn’t have an optimistic outlook in playing in other countries,” said his manager, Hillary Nikyema.

Playing the kora is a family tradition for Diabaté, who was trained by his cousin, the renowned musician Toumani Diabaté.

The kora has a deep history in Mali, where it was once only played by praise-singing poets called griots, whose role was to protect the instrument. While it is accessible to more people now, it still has deep spiritual significance to musicians like Diabaté.

Nikyema and others said what had happened to Diabaté and Sissoko was equivalent to a “hate crime”.

This feeling was especially strong because the incident with Sissoko, who is raising money for a new kora in an online fundraiser, happened a week after Donald Trump’s administration issued a new ban on people traveling from four African countries: Nigeria, Eritrea, Sudan and Tanzania.

While Nikyema said she understands most baggage handlers and security agents haven’t been exposed to a kora, she felt the damage to Sissoko and Diabaté’s instruments was so extreme she wasn’t sure damage to other foreign instruments would be prevented by providing more guidance to airline workers.

“There is a difference between Africans who travel with African instruments and Europeans who travel with European instruments,” Nikyema said. “I don’t know how seriously it would be taken.”

The stress of transporting instruments has been a key issue for the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), a union of 80,000 musicians in the US and Canada. “It’s been a problem for musicians as long as musicians have been on airplanes,” said Ray Hair, AFM’s international president.

Hair said the union began a campaign in the late 1990s to improve rules for instruments on airplanes, but their efforts were delayed after 9/11. Enhanced security measures made flying with instruments even more complicated

AFM’s guide to flying with musical instruments encourages artists to purchase insurance for the instrument before travel and to notify the airline they will be flying with that instrument. They also advise artists to carry a copy of the airline’s baggage policies.

Sometimes, though, the airlines bite back.

Is there a Mr Cello in the gate area?

There was not a world where the cellist Lynn Harrell would send his Montagnana cello, made in Venice in 1720, to the belly of the plane. Unlike with a pipa or kora, there are sophisticated hard-shell cases available to cellists, but the risk of his instrument being in the hands of a baggage handler having a bad day was too great.

“We grow up knowing the instrument itself has a soul and you bond with it. You spend all those years in a practice room all alone, except for your feelings and psychology and your instrument – it has a bonding quality,” Harrell said. “So when something happens to the instrument monetarily, that’s one thing. But the feeling that as a custodian of an instrument with hundreds of years of life, you failed – that is a scar on your soul for the rest of your life.”

This is why, like many cellists, Harrell buys his instrument a seat. He has been traveling internationally for more than 40 years and estimates he has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not millions, buying a seat for himself and his cello. Given the expense and extent of his travel, he has collected airline miles for the cello under its own account for “Cello Harrell”.

Then Delta Air Lines found out. In 2012, the company confiscated “Mr Cello’s” airline miles, as well as Harrell’s, and he has not flown with them since. Harrell and Mr Cello are still able to collect miles on other airlines.

Harrell no longer travels with the Montagnana – he sold it for $3m in 2013 after a 50-year companionship – but he has a deep bond with the replica he had made and uses for concerts today. Harrell said he hoped passengers and airline staff who saw musicians lugging instruments through airports, strapping them into seat buckles or in overhead cabins, would understand the relationship between the two is irrevocable.

“When you see someone with an instrument, recognize that to them, the instrument is almost as important as a child, as their own child,” Harrell said. “Because we make an emotional connection to it, it’s our livelihood.”