South Africans describe the pain of unemployment

A lack of social support by the community and public social welfare agencies make the experiences worse.

by Melinda Du ToitUnemployment has both individual and social consequences that require public policy interventions. For the individual, unemployment can cause psychological distress, which can lead to a decline in life satisfaction. It can also lead to mood disorders and substance abuse.

Unemployment can affect one’s social status ascription as well, which manifests through stigmatisation, labelling, unfair judgement, and marginalisation.

Both these consequences can be mitigated through public policy interventions such as social support for the unemployed, but the design of such interventions can be limited by the lack of a detailed understanding of the consequences of being unemployed. Most of the studies on unemployment experiences have been done in developed countries, with relatively few in Africa.

We sought to study the experiences of unemployed individuals in two South African townships. The aim of the study was to provide preliminary data for use in developing an intervention programme for the unemployed in Orange Farm and Boipatong, 45 km and 60 km, respectively, outside the economic hub of Johannesburg.

Both communities are characterised by high levels of poverty and unemployment, the remnants of the spatial inequality of the country’s racial past. Our research was guided by the quest to record the experiences of unemployed South Africans who live in a poor neighbourhood. South Africa has a very high unemployment rate of 29.1%. The national average belies the deepness of unemployment in certain parts of the country. In some communities, it is as high as 60%.

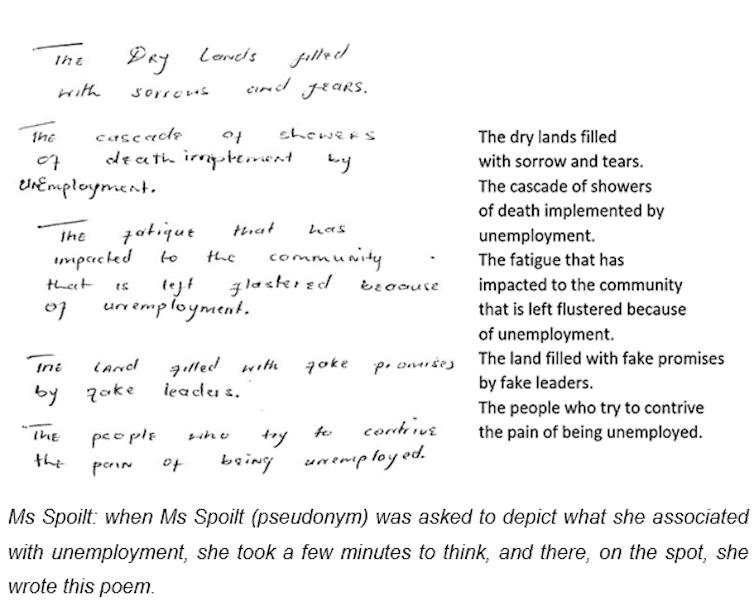

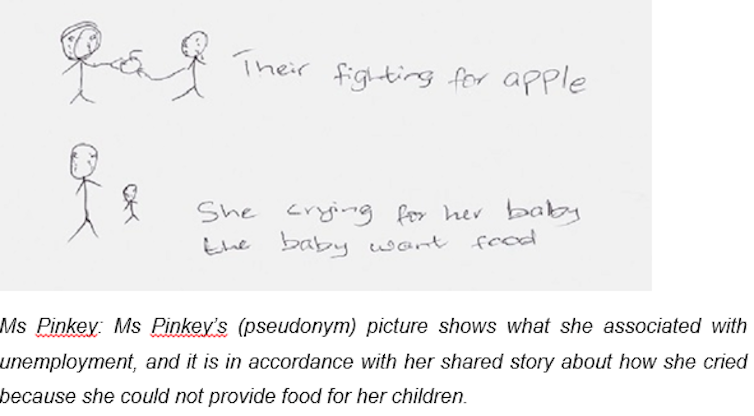

Since 2014, I have been working on community projects in Orange Farm and Boipatong in collaboration with community leaders. Our participants have typically been unemployed for six months or more. We used pseudonyms for the participants, who were aged between 20 and 64 years at the time of the study. The chosen pseudonyms brought a smile to their faces, providing a lot of light-hearted conversations at the beginning of the interviews. They chose pseudonyms that included Ms Rihanna, Ms Sunshine, Mr Star, and Mr Zionist.

The moment they shared their experiences about their daily living as unemployed individuals, however, the feeling of despair was almost tangible. They described unemployment using negative descriptions such as “a huge garbage heap filled with bad things”, “life is over”, “danger and death”, “a man-made grave”, and “a monster”.

One young participant explained that unemployment brought “a black heart full of sorrow and pain; the heart is broken, angry, sore and sad”. The words “pain” and/or “sad” were used by eight of the 12 participants.

The study had its limitations. It was exploratory and conducted in two communities, so we could gain an initial understanding of the experiences of the unemployed. Much of the context, including the respondents’ families and the perception of the broader society, was raised during the interviews. We also did not do follow-up interviews to explore more deeply issues such as the impact of negative self-stereotyping on the expectations of finding a job.

What stood out

We analysed the data looking at the questions that described the experience of being unemployed. A few aspects stood out.

- Unemployment was an extremely negative experience for all the participants. It was associated with stress, depression, and anxiety. Feelings of anger came out very strongly. Participants’ anger was mainly directed at the government. They pinned their unemployment on government’s failure to reform the economy to address the unfairness of South Africa’s past racial policies. They described nepotism, favouritism, and other forms of corruption by government officials as contributing to unemployment. Seeing their families, especially their children, suffering and not getting any assistance, either from businesses, government, or non-governmental organisations, angered the participants. They described their communities as filthy, painful, sad places that had been forgotten. They also had dilapidated infrastructure. The townships offered no job opportunities. They were far removed from the country’s economic hubs, making it that much more difficult for the unemployed to find work.

- Most of the participants regarded their township environment and their immediate neighbourhoods as unsupportive, adding to their negative experiences of being unemployed. They reported experiences of stigmatisation and shame because they believed that society perceived them as not honestly trying their best to find work. This finding is well supported by the literature. The participants explained how they were judged harshly by their community members, who described them as “lazy and do not want to work”. Community members were also prejudiced: “When something is stolen, they look at us who are unemployed and believe we steal and cheat.” Participants suffered negative social labelling:

The others still call me a boy, because I cannot provide for my family.

Greater understanding

As these findings show, a lack of social support by the community and public social welfare agencies make the experiences of the unemployed worse. Public policy interventions are required to help connect unemployed people to job networks. There is also a role for public policy to help them deal with the stigma and all the other negative stereotypes associated with unemployment. Psychologists and social scientists can assist people to cope with unemployment as well as improve their psychological wellness, but designing such interventions requires a greater understanding of the experiences of the unemployed.

Melinda Du Toit is a Post-doctoral Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Development in Africa, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.