The Wuhan coronavirus seems to have a low fatality rate, and most patients make full recoveries. Experts reveal why it's causing panic anyway.

by Holly Secon- The outbreak of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, has sparked fear and anxiety around the world despite the virus’ low fatality rate.

- People’s psychological reactions to infectious diseases can sometimes be overblown and do more harm than good, some experts say.

- Still, preventative measures like increased handwashing and not touching your face protect against coronavirus and other illnesses.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

The outbreak of a new coronavirus has sparked fear and anxiety around the world.

The pneumonialike virus, which originated in Wuhan, China, has infected more than 9,700 people and killed 213.

So far, the virus does not seem to be as deadly as SARS, which killed 774 people from 2002 to 2003. SARS had a mortality rate of 9.6%, whereas about 2% of people infected with the new coronavirus have died. But the number of people infected after one month has already surpassed the SARS outbreak’s eight-month total.

Many patients with coronavirus have already made full recoveries. According to Chinese officials, most of those who’ve died were elderly or had other ailments that compromised their immune systems.

Experts say that for the most part, global panic over the Wuhan coronavirus is unproductive and unwarranted: The public should take precautions to avoid getting sick, but the most effective preventative measures are everyday actions like increased handwashing and not touching your face.

An expert also said fear would not stop the spread of the virus and could cause negative social impacts.

“There’s the spread of infectious disease, then there’s the spread of panic,” Amira Roess, a professor of global health and epidemiology at George Mason University, told Business Insider. “They have very different mechanisms.”

In the early stages of an infectious-disease outbreak, Roess added, much of the panic is “fear of the unknown.”

The spread of disease and the spread of fear

Psychological research shows novel threats raise anxiety levels more than familiar threats and that people tend to underreact to familiar threats.

For example, there’s about a one-in-seven chance that heart disease will be the cause of an American’s death, whereas the chance they will die at the hands of a foreign-born terrorist is one in 45,808. But according to a 2016 Chapman University survey of American fears, “terrorist attack on nation” and “victim of terrorism” both ranked among the top five worries of the respondents.

This dynamic played out during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa from 2014 to 2016, according to Paul Slovic, a psychologist and the president of the nonprofit Decision Research.

“What happened was quite consistent with what we know about risk perception,” Slovic wrote in an article for the American Psychology Association. “The minute the Ebola threat was communicated, it hit all of the hot buttons: It can be fatal, it’s invisible and hard to protect against, exposure is involuntary, and it’s not clear that the authorities are in control of the situation.”

Past outbreaks of Ebola, however, had much higher death rates than SARS and the new coronavirus: 25 to 90%. Worldwide, Ebola has killed more than 33,000 people since 1976.

Racist consequences of panic

Nationals of Asian descent in France, Canada, and the US are reporting incidents of racism because of public fears of the Wuhan coronavirus.

The Guardian reported nearly 9,000 parents near Toronto have signed a petition to prevent students who had traveled to China in the past 17 days from attending school.

“This has to stop. Stop eating wild animals and then infecting everyone around you,” one petition signer wrote. “Stop the spread and quarantine yourselves or go back.”

The New York Times reported that businesses throughout Hong Kong, South Korea, and Vietnam have posted signs telling customers from mainland China they are not welcome.

Asian students at Arizona State University, meanwhile – where a US case of coronavirus was confirmed – said they were facing jokes, stares, and isolation on campus.

“I cough in class and everybody looks at me,” a Vietnamese American freshman at ASU told Business Insider’s Bryan Pietsch.

Misinformation about the coronavirus has spread as well – no, oregano oil will not cure it, nor will drinking bleach.

Reasons for hope during this coronavirus outbreak

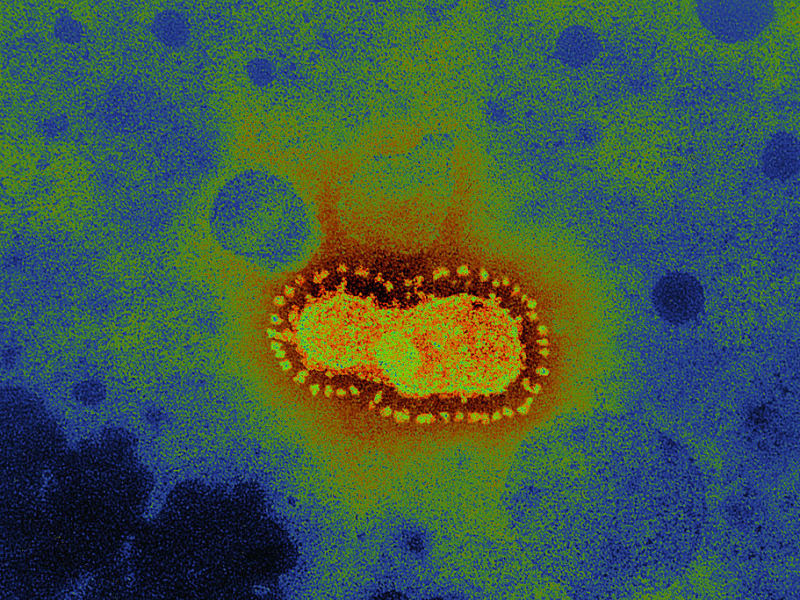

Experts say a few factors should ease fears about the coronavirus: First, it was identified and determined to be a new virus more quickly than ever before. A week after it was discovered, Chinese authorities had already sequenced the virus and shared it with labs around the world.

“Something that’s remarkable here is that within a week, the RNA sequences of the virus are available on the internet, and many can look at it and begin to understand it,” Richard Martinello, an associate professor of infectious disease at the Yale School of Medicine, told Business Insider. “That’s something that’s never been done before.”

Second, a variety of advancements in medical technology since coronaviruses were discovered in the 1960s have allowed clinical labs and virologists to conduct more in-depth research into the way these zoonotic viruses work.

For example, though scientists knew coronaviruses could infect humans because they’re a cause of the common cold, the SARS outbreak marked the first time a coronavirus was traced back to animals. (It’s possible, however, that coronaviruses from animals have made people sick in the past, Martinello said.)

Martinello also said people in the US were far more likely to catch the seasonal flu than the Wuhan coronavirus. At least 15 million Americans contracted the flu in the last four months, but because the peak of flu season is between December and February, the worst could be still to come.

The preventative measures for both the flu and the coronavirus are the same: handwashing, avoiding face touching, and steering clear of contact with anyone who’s sick.

However, the familiarity of the seasonal flu means the general public usually doesn’t perceive it as a threat and underreacts to it. Martinello hopes that the widespread worry about the coronavirus could unintentionally lead to lower rates of seasonal flu this year as people take better precautions.