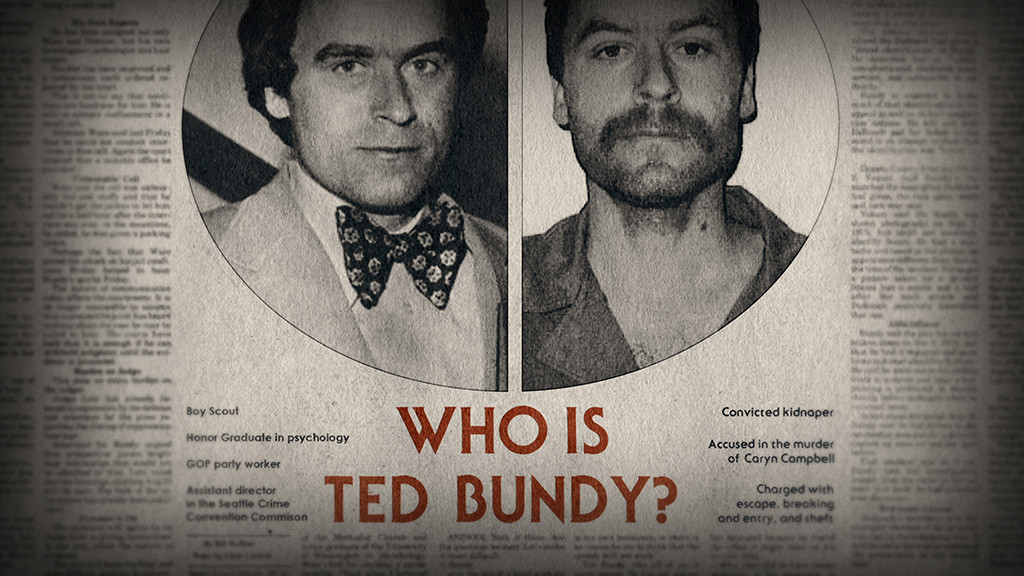

Inside the Horrific Legacy of Serial Killer Ted Bundy

by Natalie Finn

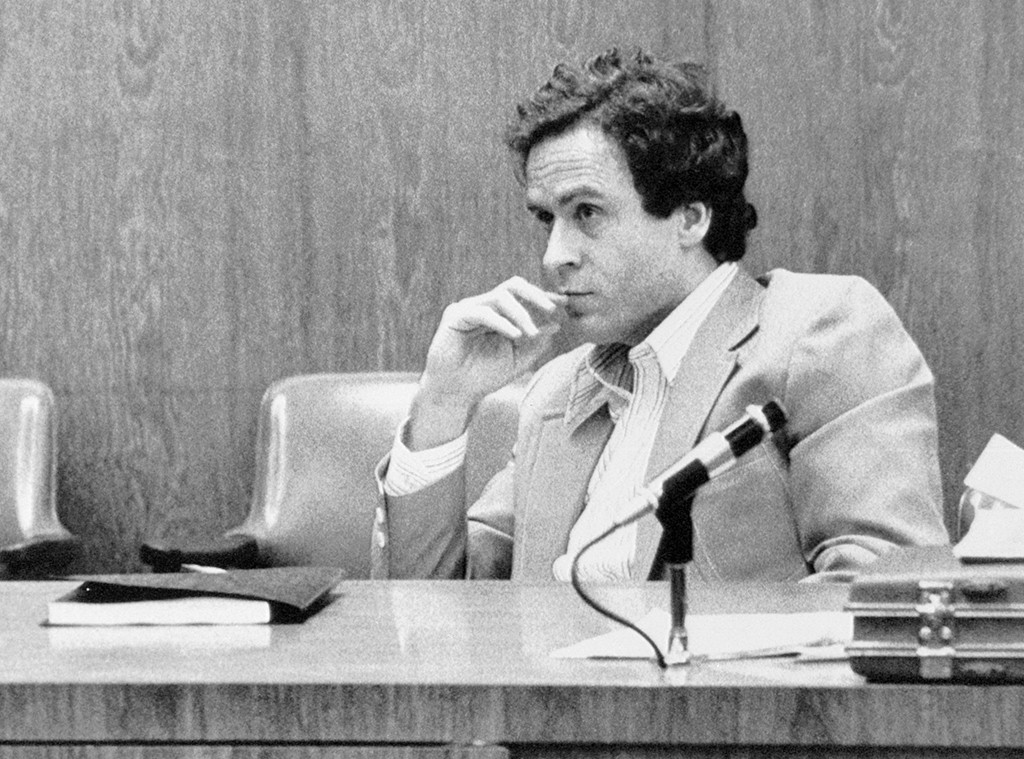

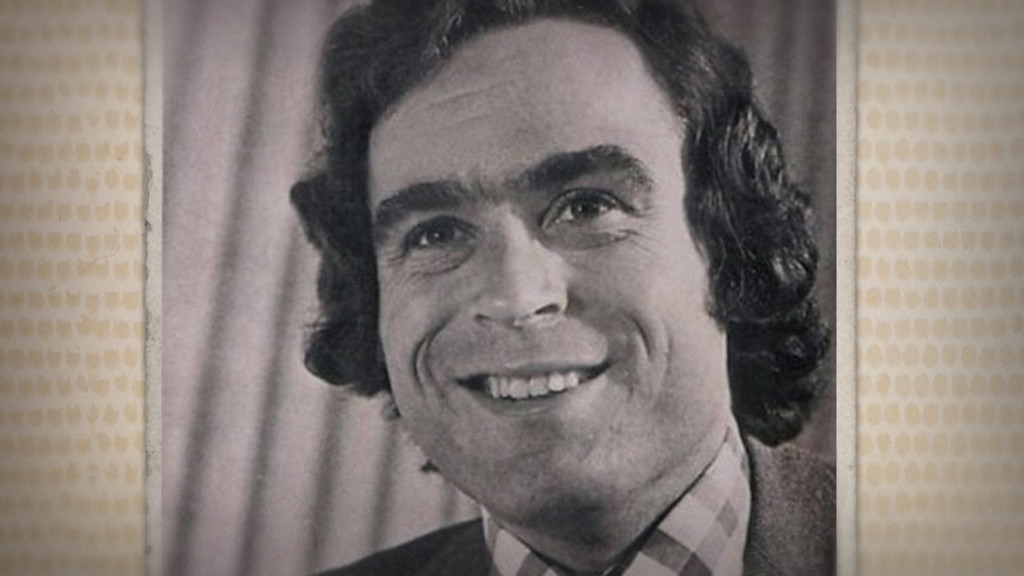

Looking at photos of Ted Bundy now, it's hard to see what unsuspecting people saw in the 1970s.

Which, according to so many, was a handsome, charming man.

That's been the forever-buzz on Bundy, the serial killer who was executed 31 years ago and, when his story is being told onscreen, has historically been played by unarguably good-looking men, including Mark Harmon, Cary Elwes, Billy Campbell, James Marsters, Adam Long and, just last year, Zac Efron—all ways of illustrating how he was a guy who had no problem getting women to let their guard down around him due to his numerous outwardly socially acceptable traits.

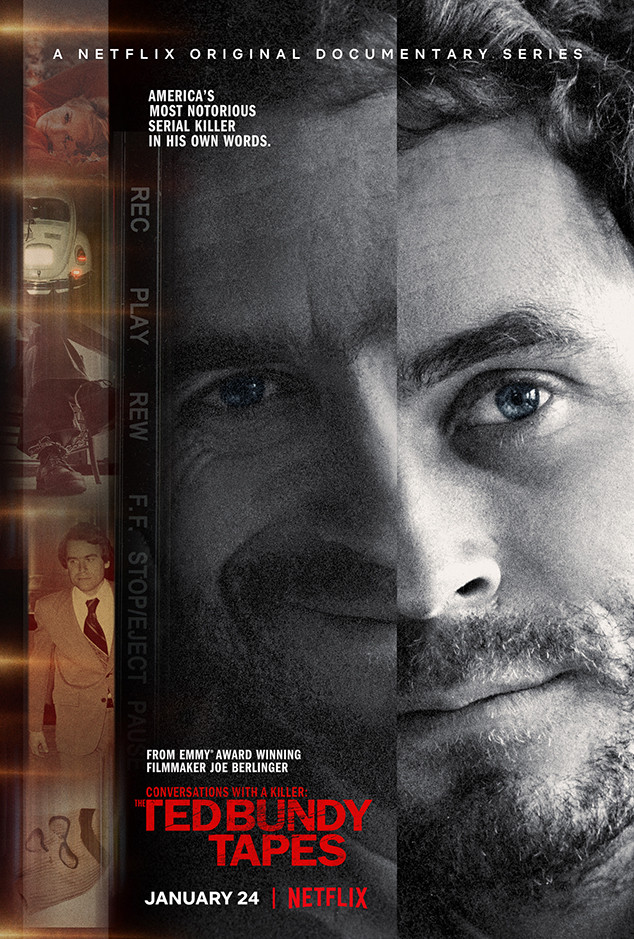

"Bundy represents for us our most primal, deepest, darkest fear, which is that you don't know the person next to you," Joe Berlinger, director of the Efron film, the aptly titled Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, and executive producer of Netflix's Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, told E! News last year.

"We want to think that serial killers are easily identifiable, that once you see them you know, 'OK, that guy must be a serial killer,'" Berlinger continued. But "people really liked him."

And they liked him until the day he died at 42 years of age in the electric chair at Raiford Prison after confessing to the murders of 30 women.

"I shouldn't be surprised that I still get letters and emails from twenty-year-olds who are fascinated with Ted Bundy," wrote Ann Rule in a 2009 update to her 1980 best-seller The Stranger Beside Me (which was made into a 2002 TV movie starring Campbell as Bundy). "Thirty years ago, I watched the Florida girls who lined up outside the courtroom in Miami, anxious to get a place on the gallery bench behind his defense table.

"They gasped and sighed with delight when Ted turned to look at them."

Rule, who died in 2015, befriended Bundy after meeting him at, of all places, a suicide hotline office in Seattle where they were both answering phones on the night shift.

The true crime renaissance has of course taken on a shade of the glamorous thanks to trending podcasts, probing documentaries and deep-pocketed, savvily written limited series that have been dominating the major award shows. Usually the glamour almost never stops and starts with the killer himself, but Bundy proved the exception to that rule almost from the beginning, with first the very appealing Harmon playing him in the chilling 1986 TV movie The Deliberate Stranger, while the killer was still on death row.

"It doesn't really glorify Ted Bundy," Efron told Entertainment Tonight in March 2018 about Extremely Wicked. "He wasn't a person to be glorified. It simply tells a story and sort of how the world was able to be charmed over by this guy who was notoriously evil and the vexing position that so many people were put in, the world was put in. It was fun to go and experiment in that realm of reality."

And it is exponentially more chilling when the devil comes calling looking like... well, like Zac Efron.

"Ted was never as handsome, brilliant, or charismatic as crime folklore has deemed him," Rule wrote. "But, as I have said before, infamy became him...I always believed that time would blur the interest in Bundy, particularly after his execution. Instead, he has become almost mythical."

Bundy wasn't a mastermind. Countless women refused his ruse, which usually included a request to accompany him to his car for some reason, meaning he left witnesses behind practically everywhere he went and circumstantial evidence abounded in his car and apartment. Yet at the same time, he was both unassuming and handsome enough not to trigger alarm bells for lord knows how many people, some of whom didn't know how lucky they were to live to tell the tale of the cute fellow who approached them at the park, or beach or bus stop.

He blended in, and even though dozens of people saw his ultimately infamous tan Volkswagen Beetle, that didn't stop him from driving it across state lines, back and forth. And he was brazen, sometimes driving for hours with dead girls in his car, and returning multiple times to where he dumped their bodies to visit their remains.

"Intellectually, I've always known that Bundy is somebody who did not act the way he appeared to many," Berlinger says. "But by experiencing these tapes, we get an understanding into how somebody like that could be believable to so many, and yet capable of such evil."

What he was, any way you look at him now, was a monster.

Berlinger explained last year that, aside from it being the 30th anniversary of Bundy's execution, the impetus for the Netflix series was their acquisition of taped interviews that journalists Stephen G. Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth conducted with the murderer on death row in 1980. (Extremely Wicked was also ultimately bought by Netflix to distribute after it premiered at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival.)

"It's entering into the mind of a killer," Berlinger says, "to understand how somebody could be so deceptive, so manipulative, and what makes him tick. I think it'll be utterly fascinating for people."

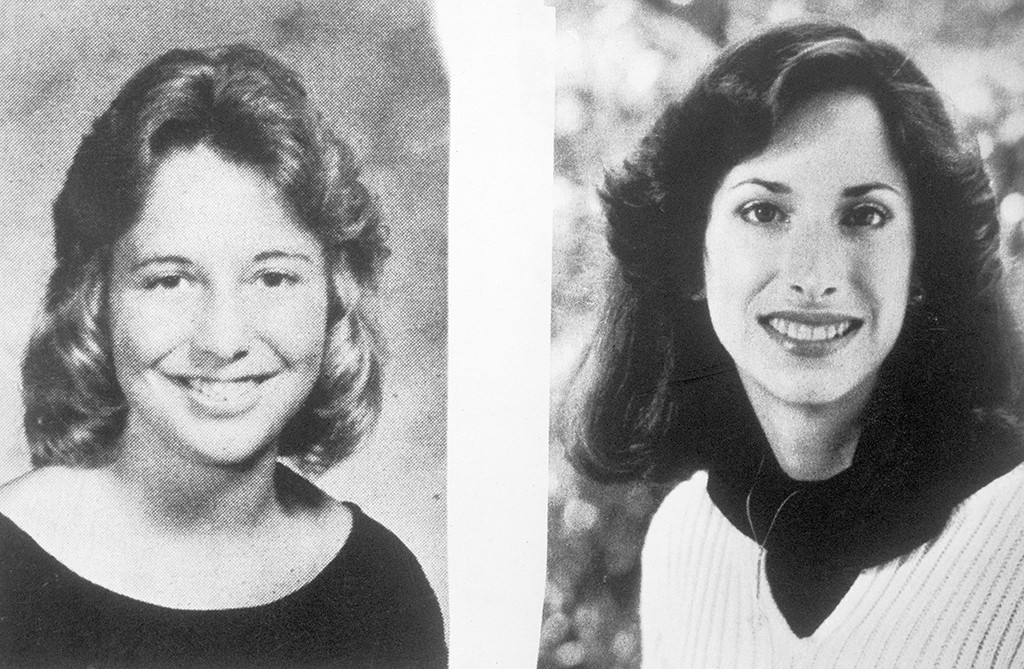

In their 1983 book The Only Living Witness, since updated, Aynesworth and Michaud call Bundy "handsome, arrogant and articulate." Women of all ages, not just misguided twentysomethings, flocked to get a glimpse of him when he went on trial in Miami for murdering two Florida State sorority sisters and attacking two others, as well as another student in an apartment eight blocks away, in a bloody spree on Jan. 15, 1978. All three survivors testified at trial.

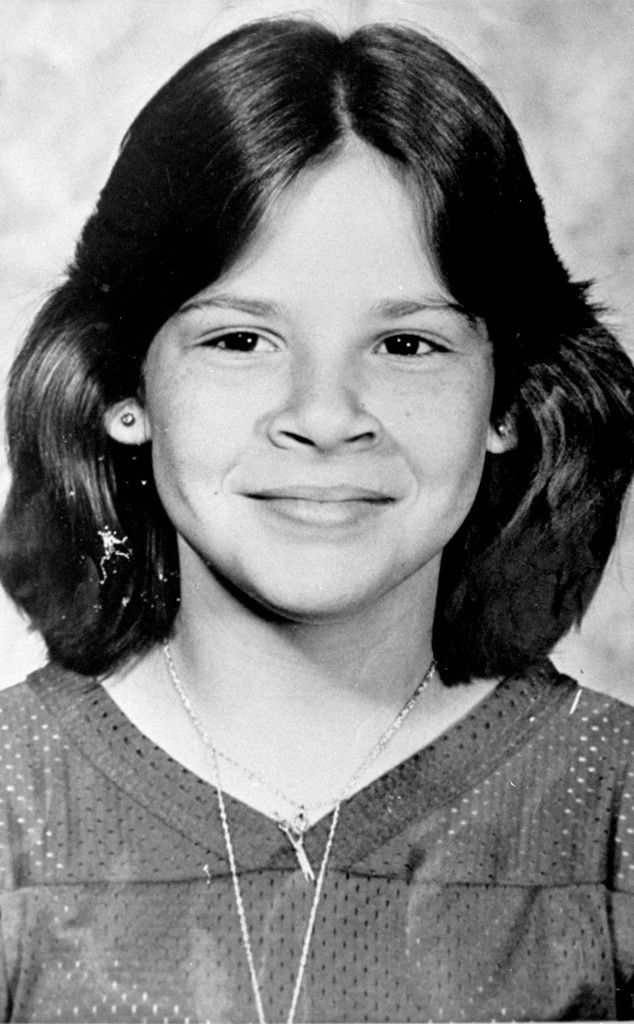

Bundy went on trial again in Orlando for the Feb. 9, 1978, kidnapping and murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach.

He was convicted and sentenced to death for all three murders, though technically the crime he was executed for was killing Leach, a junior high student who disappeared from school on her way to her homeroom class to retrieve her purse. Her remains were found seven weeks later in a hog shed by Suwannee River State Park, in Live Oak, Fla.

Ultimately, however, these three murders were the sloppy climax of Bundy's epic display of savagery wrought over four years in seven states. Before he was executed he confessed to 30 killings, which doesn't mean he wasn't responsible for more, and over the years he played along with the not far-fetched assumption that he may have been responsible for at least 100 murders, not including numerous attacks.

"I don't think even he knew...how many he killed, or why he killed them," said the Rev. Fred Lawrence, who administered Bundy's last rites, according to David Von Drehle's 1995 book Among the Lowest of the Dead: The Culture of Death Row.

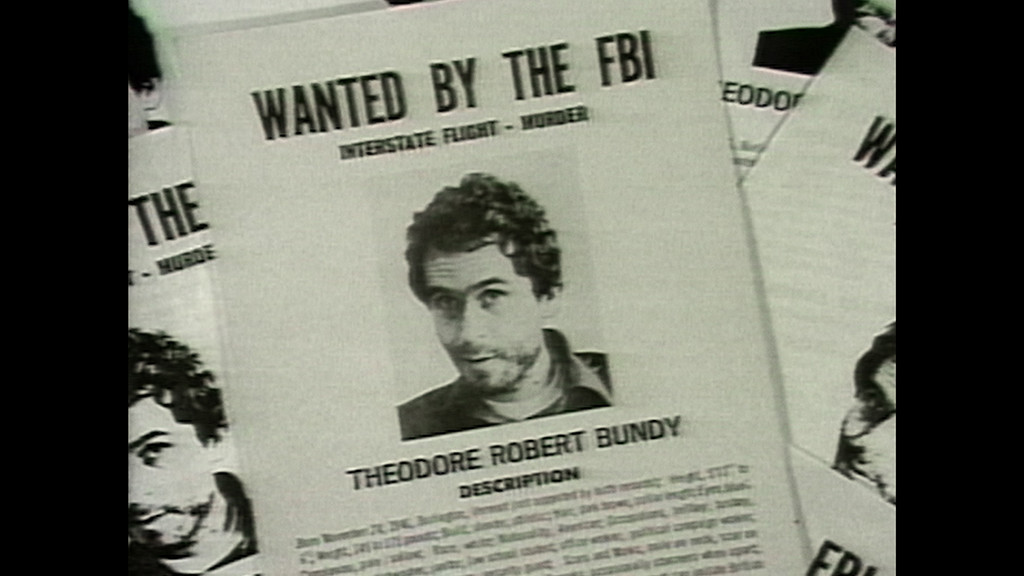

The nature vs. nurture debate is one for the ages, but the man born Theodore Robert Cowell is ripe for discussion.

His mother, Eleanor Louise Cowell of Philadelphia, gave birth to him at a home for unwed mothers on Nov. 24, 1946, sent there by her deeply religious parents, who at first set about raising him as their own so as to spare themselves the shame of having an illegitimate grandson.

His birth certificate lists a salesman named Lloyd Marshall as his father, though his mother later mentioned being seduced by "a sailor." Yet another theory is that his maternal grandfather—a violent, abusive man—was his biological father.

Cowell moved 4-year-old Ted to Washington in 1950 and married Johnnie Bundy two years later, but though Ted had his adoptive father's name, he didn't have a close relationship with him or his step-sisters and resented being moved away from the grandfather who he thought was his dad (and maybe was his dad). When Bundy ultimately found out about his parentage, he resented being lied to, regardless.

Before he turned 18, Bundy was arrested twice for burglary and car theft, but nothing violent. However, when he was 14, an 8-year-old girl who took piano lessons from his uncle disappeared. Down the road, Bundy actually denied having anything to do with that and there's no proof that he did, but Ann Rule, among others, believes the child was Bundy victim No. 1.

The shy teen enrolled at University of Puget Sound, then transferred to University of Washington, where he started dating classmate Stephanie Brooks (a much-used pseudonym). Bundy dropped out of college in 1968 and Brooks broke up with him shortly afterward, citing his lack of seriousness and ambition, and he ended up leaving town, eventually ending up at Temple University for one semester.

Once back in Washington, he met Elizabeth Kloepfer, a divorced secretary at the UW School of Medicine, and they dated off and on for years. Now Elizabeth Kendall, it's her take that's at the center of the new Amazon Prime docu-series Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer, timed for the re-release of her 1981 book The Phantom Prince: My Life With Ted Bundy.

He re-enrolled at UW in 1970, met Rule as a volunteer at Seattle's Suicide Hotline Crisis Center in 1971 and graduated in 1972. Bundy, who had attended the Republican National Convention in 1968 as a delegate for Nelson Rockefeller, went to work for Gov. Daniel Evans' successful reelection campaign. That opened a few more doors in the political world, and then he was admitted to law school at Puget Sound.

According to Rule, he rekindled his relationship with Brooks during a trip to California in the summer of 1973, then broke off contact with no explanation. When she reached him by phone to ask what happened in early 1974, he calmly said, "Stephanie, I have no idea what you mean," and hung up.

Within a few months Bundy had pretty much stopped attending class at UPS and became assistant director of the Seattle Crime Prevention Advisory Commission.

Also in 1974, eight college students disappeared in Washington and Oregon between February and July, all killings Bundy confessed to in his 11th hour, though only seven sets of remains were found.

Bundy later told his last attorney, Polly Nelson, that he first attempted a kidnapping, in New Jersey, in 1969 (the timeline of his whereabouts fits) and first killed someone in 1971, in Seattle. However, he also told a psychologist that he killed two women in Atlantic City in 1969.

He was a murderous liar, after all.

As authorities investigated the sudden glut of missing girls in the first half of 1974, multiple witnesses came forward to report being asked by a young man with one arm in a sling, or on another occasion a guy on crutches, for help carrying a stack of books or a briefcase, to a VW Bug.

Meanwhile, Bundy was working at the Department of Emergency Services in Olympia, which was involved in the search for the missing co-eds.

On July 14, when both Janice Anne Ott and Denise Marie Naslund disappeared from Seattle's Lake Sammamish Park within hours of each other, five women reported that a young man in tennis whites, left arm in a sling, had asked for help unloading a sailboat from his car. One went with him but turned and ran when she glimpsed that there was no boat.

Kloepfer, Rule and a psychology professor at UW recognized Bundy when authorities shared a suspect profile, a composite sketch of the suspect and a description of him and his car. Rule recalled that police were skeptical of the idea that a clean-cut law student could be responsible.

Transferring to law school at University of Utah, Bundy moved to Salt Lake City in August 1974—where he quickly found out that he was out of his league intellectually when it came to legal studies, and young women started disappearing.

He later confessed to killing three teenage girls that October, and on Nov. 8 he killed 17-year-old Debra Jean Kent—hours after he attempted to abduct 18-year-old Carol DaRonch. He had approached DaRonch at a mall, posing as a police officer, and told her someone had tried to break into her car and would she accompany him to the station to file a report. When he pulled over and attempted to handcuff her, she struggled and he ended up only getting the cuffs around one wrist, giving her a chance to get out the door and escape.

Kent was last seen leaving a high school theater production on the way to pick up her brother. Investigators later found a key near the auditorium—it was the key to the handcuffs DaRonch fled with, dangling from one wrist.

"He drove a Volkswagen, which I thought, 'well that's kind of odd,' but maybe he's undercover," DaRonch remembers in Conversations With a Killer. "And I got in." When she realized what was happening, "I had never been so frightened in my entire life. And I know this is cliche but my whole life went before my eyes. I thought, my god, my parents are never going to know what happened to me."

A 62-year-old grandmother named Rhonda Stapley talked on Dr. Phil a few years ago about narrowly escaping Bundy's clutches in October 1974, when she was a pharmacy student at the University of Utah. She was at a city park, waiting for a bus to go back to campus, when a cute guy in a tan VW Beetle pulled up and asked if she wanted a ride.

"The first thing I noticed was, the inside passenger door handle was missing," Stapley said. She wasn't immediately alarmed, she added, figuring "college kid, college car. Things fall off."

She acknowledged that she wasn't concerned because he was a well-dressed, nice-looking young man who fit the collegiate mold. But then he asked if it was alright if they took a quick detour. She was OK with it, but first he didn't go exactly where he said he was going, and then instead of taking an exit toward campus, he started driving on a canyon road. "He stopped talking to me and I'm still trying to make idle conversation," Staple recalled, but she initially only suspected that he was looking for a place to pull over and try to make a pass at her.

He eventually pulled into a parking place and stopped the car. "I thought he was going to kiss me. Instead he said, very quietly, 'Do you know what? I'm going to kill you.' And he put his hands on my throat and started squeezing." She still thought for a split second he was joking. Then, Stapley says, she tried to fight him off but lost consciousness, and he raped her. Then woke her up and did it again.

"So I was kind of in a state of going into unconsciousness for most of the evening," Stapley said. "The last time I regained consciousness...the passenger door was open and the dome light was on. So I could see him, that was the only light in the whole canyon...I could see him standing over there, facing away from me, doing something in the backseat of the car."

She saw an opportunity to escape and took it. "I just jumped and ran in the other direction, into pitch blackness," Stapley said. "I just took a couple of steps because my pants had been pulled down around my ankles. So I tripped...and tumbled, but I fell into a mountain river that wasn't really deep, but it was really, really swift. There were boulders and bushes and tree limbs sticking out...the water swept me away from him, and it's probably what saved my life."

Stapley told her husband she had been sexually assaulted when they were first married, but never came forward with her Bundy story for decades, when a bout of PTSD pushed her memories to the surface. Back in 1974, "the first thing I thought [was], 'No one can ever know...everyone would think it was my fault. Why would I get in the car with a stranger?'"

It was Ann Rule's publisher who helped shepherd her own book, I Survived Ted Bundy: The Attack, Escape & PTSD That Changed My Life, to the finish line.

"There's no group of Ted Bundy survivors that I could sign up and join," Stapley told People in 2016. "But there are other people who have experienced trauma. They can understand not wanting to tell, and the shame and embarrassment and all those things that go along with rape."

Toward the end of 1974, Elizabeth Kloepfer, who had remained in Seattle, called police in Salt Lake City to report that she believed her boyfriend, Ted Bundy (he dated a string of women in Utah, in the meantime), might have something to do with the sudden spate of missing women.

Witnesses from the Lake Sammamish abductions failed to identify him in a photo lineup, however, so Bundy was added to a list of suspects and remained there.

Kloepfer also continued to see him.

"The public continues to be drawn to Bundy partly because of the questions his friendly and handsome façade brings out," says Rachael Penman, director of artifacts and exhibits at Alcatraz East Crime Museum, where Bundy's car and other items, including a letter he wrote to Elizabeth Kloepfer, are currently on display. "The warning of 'stranger danger' is something we always try to bring home to our visitors, but it goes beyond that because Liz stayed with him even after reporting him to the police."

And Bundy maintained this relationship with Kloepfer, Berlinger says, "because he had this need for normalcy. He compartmentalized his life, so he actually lived with a woman who thought he was prince charming. He was a wonderful boyfriend and, by all accounts, a wonderful surrogate father to the daughter of Elizabeth."

Their relationship that abetted Bundy's double life is also at the center of Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, with Lily Collins playing Kloepfer opposite Efron. The title, incidentally, is taken verbatim from what the judge called Bundy as he sentenced him to death.

On Jan. 12, 1975, a 23-year-old nurse disappeared from a ski lodge in Snowmass, Colo.; her body was found the next month. Then, on March 15, a 26-year-old ski instructor disappeared in Vail, Colo.; Bundy later said he approached her on crutches and asked if she could help carry his boots to his car.

According to Bundy, he proceeded to kill at least three more women, in April, May and June, in Colorado, Idaho and Utah.

In mid-May 1975, some of his old colleagues from the Department of Emergency Services, including Carole Ann Boone, whom he had dated in Washington, came to visit and stay with him in Utah. He and Boone rekindled their relationship, but he also went to visit Kloepfer, who didn't tell him she'd been in contact with the police on multiple occasions. He, in turn, didn't mention he was seeing other women.

"I liked Ted immediately. We hit it off well," Boone said, according to The Only Living Witness. "He struck me as being a rather shy person with a lot more going on under the surface than what was on the surface. He certainly was more dignified and restrained than the more certifiable types around the office. He would participate in the silliness partway. But remember, he was a Republican."

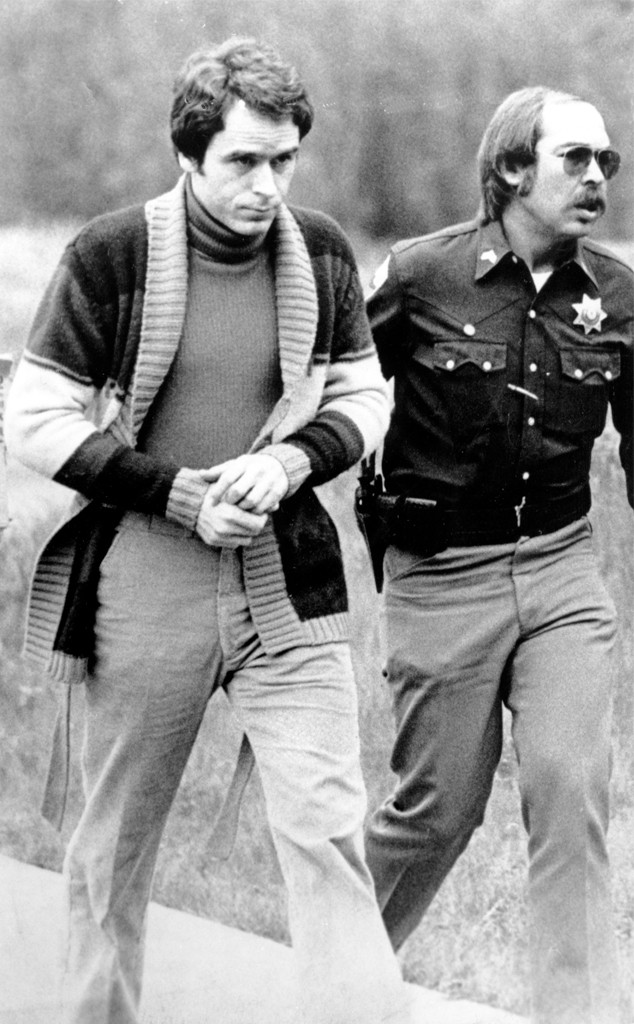

In 1975, Utah Highway Patrol observed Bundy driving slowly around a residential neighborhood in the early morning hours of Aug. 16; when he spotted the patrol car, Bundy sped off and the officer gave chase.

When he finally pulled him over and searched the car, the officer found a ski mask, another mask fashioned out of pantyhose, an ice pick, rope, handcuffs and a crowbar. DaRonch's description of the car her attempted abductor was driving, combined with Kloepfer's December 1974 phone call to Salt Lake police, were enough to get a warrant to search Bundy's apartment, where they found a guide to Colorado resorts, including where the ski instructor disappeared, and a brochure for the play at the school where Debra Jean Kent was abducted.

That wasn't enough evidence to arrest him, however, so police released Bundy on his own recognizance and watched him 24/7.

In September 1975, Bundy sold his car and police swooped in for a deep search, during which they discovered hair that matched samples from the body of Caryn Campbell, the nurse who became Bundy's first known victim in Colorado in 1975, as well as indistinguishable hair matches for Melissa Smith, one of the 1974 Utah victims, and DaRonch.

The following month DaRonch identified Bundy in a lineup as the "officer" who had tried to abduct her and he was promptly charged with aggravated kidnapping and attempted criminal assault. His parents paid the $15,000 bail to get him released. There was not enough evidence to charge him in any of the disappearances or suspected murders to date.

In February 1976, a judge found Bundy guilty in a bench trial of kidnapping and assault and sentenced him to 1 to 15 years in Utah State Prison. Later that month, he was charged with Campbell's murder in Colorado.

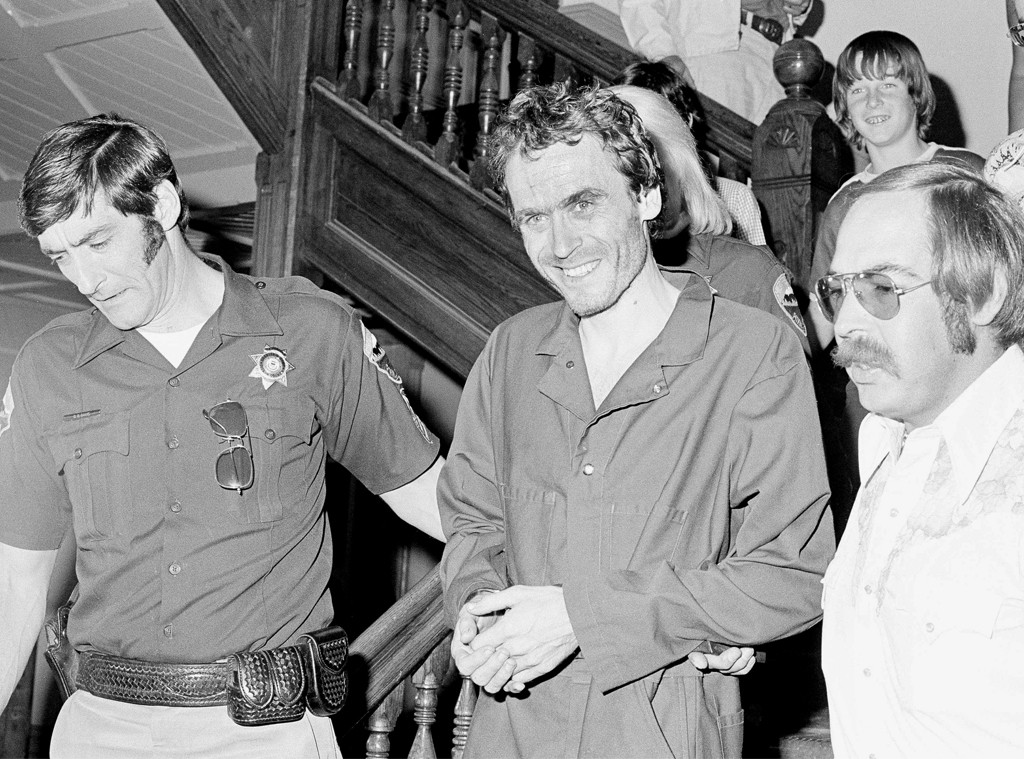

During a preliminary hearing in Aspen in June 1977, Bundy, who had elected to represent himself and therefore wasn't wearing leg restraints, jumped out of a second-story window in the law library of the Pitkin County Courthouse, broke into a cabin to steal clothes, food and a rifle, and ended up lost in the woods for a couple of days. He managed to elude road blocks and other patrols for several days until he stole a car and police saw him weaving between lanes.

On the night of Dec. 30, he broke out of jail, managing to fool the holiday-time skeleton staff with a lump of books in his bed, covered with a blanket, while he escaped via a crawl space in the ceiling. He said Carole Ann Boone brought him $500 over the preceding six months to aid his escape.

Bundy stole a car, which broke down on Interstate 70, and then hitched a ride to Vail, where he caught a bus to Denver. From there, he flew to Chicago, and was in the Windy City by the time the manhunt began.

From Chicago he caught a train to Ann Arbor, Mich., where he went to a bar and watched Washington play Michigan in the Rose Bowl. He stole another car and drove to Atlanta, and from there took a bus to Tallahassee, Fla. He rented a room and tried to get a job doing construction, but when they asked for identification he resorted to shoplifting and stealing from women's wallets if he spotted one out in the open at a store.

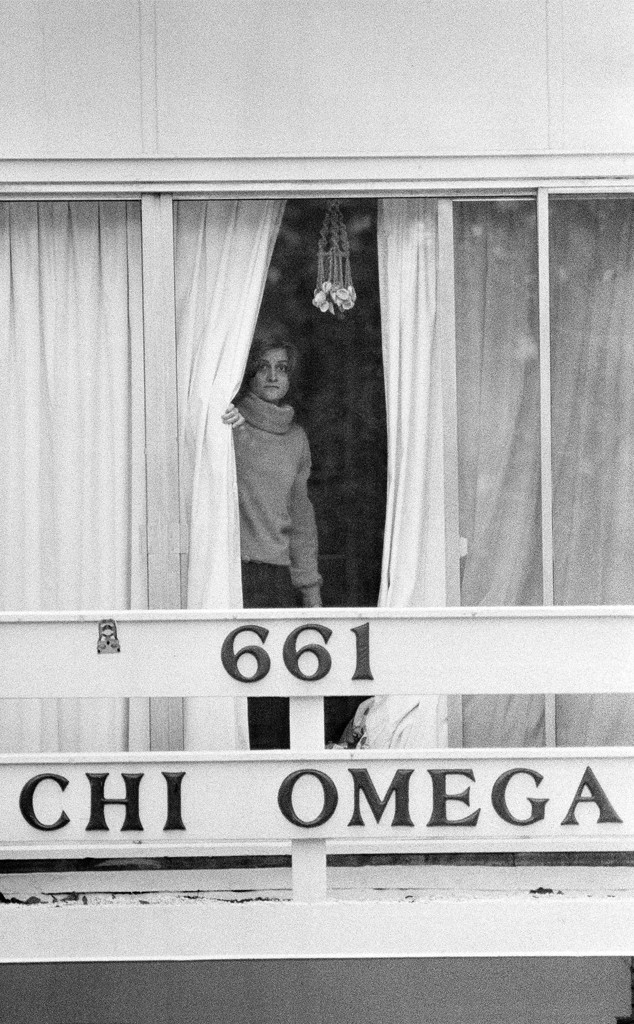

In the early morning hours of Jan. 15, 1978, Bundy snuck into the Chi Omega sorority house on the Florida State campus and proceeded to beat and strangle Margaret Bowman, 21, and, in a separate bedroom, Lisa Levy, 20. He also bit Levy multiple times, earning himself the nickname "the Love-Bite Killer" when he went to trial.

Bundy also attacked Chi Omega roommates Kathy Kleiner and Karen Chandler, both of whom suffered broken jaws and other injuries, but survived.

The entire spree lasted roughly 15 minutes, authorities estimated.

He then left the sorority house and, eight blocks away, he savagely beat FSU student Cheryl Thomas in her apartment. Police later found a semen stain on her bed.

Bundy remained at large for weeks. On Feb. 8, he approached 14-year-old Leslie Parmenter, who happened to be the daughter of the Jacksonville Police Chief of Detectives, but her older brother showed up and he took off.

The fugitive then drove west to Lake City, Fla., where he kidnapped and murdered 12-year-old Kimberly Leach.

Finally, at around 1 a.m. on Feb. 15, 1978, Bundy was pulled over driving a stolen vehicle—a VW Bug, no less—near the Alabama border by a Pensacola police officer who ID'd the car as stolen. When Officer David Lee went to place Bundy under arrest, he kicked Lee and took off running. Lee fired a warning shot, gave chase and tackled Bundy, finally wrangling him under control. A subsequent search of the car turned up three FSU ID cards belonging to female students, 21 stolen credit cards and a stolen TV set.

"I wish you had killed me," Bundy told Lee as he took him into custody, the officer not yet realizing he had nabbed a convicted kidnapper and murder suspect on the FBI's 10 Most Wanted list.

On Feb. 8, 1980, during the penalty phase after being found guilty of murdering Leach, Bundy (again, defending himself) proposed to Carole Ann Boone, who testified as a character witness for him, while she was on the stand. He had arranged for a notary to be present and officials said the marriage was legal after they said their I-dos right there.

The same day, the jury recommended he be executed for his crimes.

In 1981, Boone turned up pregnant, insisting it was Bundy's baby but it was "nobody's business" how they managed because conjugal visits technically were not allowed at Raiford Prison. "I don't have to explain anything to anyone about anything," Boone told the Orlando Sentinel Star.

Boone, who had two children from her previous marriages, gave birth to a daughter named Rose in 1982. According to a Bundy site maintained by Ann Rule, Boone divorced Bundy in 1986, three years before he was executed. He originally was going to be executed that year for the Chi Omega killings, but that execution was stayed indefinitely by the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Despite the oodles of groupies he amassed over the years, there were far more people who were glad to see him go on Jan. 24, 1989.

"I've never spoken to anybody about this, but I'm looking for an opportunity to tell the story as best I can," Bundy tells Michaud and Aynesworth in a recording played in Conversations With a Killer.

"I mean, I'm not an animal and I'm not crazy. And I don't have a split personality," he says. "I mean, I'm just a normal individual."

All five episodes of Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer are streaming now on Amazon Prime.

(Originally published Jan. 24, 2019, at 3 a.m. PT)