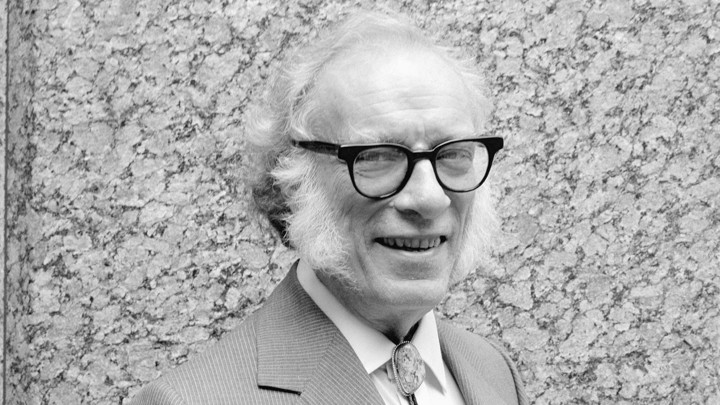

Isaac Asimov’s Throwback Vision of the Future

by Yosef LindellWhen Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy won the Hugo Award for best all-time science-fiction series, in 1966, no one was more surprised than the author. The books contained “no action,” Asimov complained years later, adding, “I kept waiting for something to happen, and nothing ever did.” As a young reader, I devoured the Foundation books, the short-story collection I, Robot, and other works by Asimov. Though these tales entranced me with their bold strokes of imagination, when I revisit them as an adult, their flaws stand out more than their virtues. It’s not so much that nothing happens, but that the reader doesn’t get to see anything happen. Asimov’s stories are dialogue-driven; the action happens off-stage while men (and, less frequently, women) huddle to debate the significance of what occurred or what ought to be done in the best Socratic fashion.

Asimov was aware of these quirks. “I don’t see things when I write,” he once apologized. “I hear, and for the most part, what my characters talk about are ideas.” Still, his stories often evoke the smoke-filled corporate boardrooms of the past century more than a progressive tomorrow. And his writing is striking for its optimism, betraying a faith in technology and humanity that seems especially naive and out of place today. When considering Asimov’s tales now, I’m reminded of what another famous science-fiction author, Neil Gaiman, once cautioned about rereading older works in the genre: “Nothing dates harder and faster and more strangely than the future.” (It doesn’t help Asimov’s case that he was known for groping women, an aspect of the author’s legacy that Alec Nevala-Lee wrote about in depth for Public Books earlier this month.)

Asimov, who would’ve turned 100 this year, remains among the most recognizable names in science fiction, living or dead. The Foundation novels appear on lists of best-loved books, and Apple TV is adapting the series nearly 70 years after its first book was published. Asimov’s other novels continue to be reprinted too, with many readers drawn to his lucid prose and page-turning (if conversation-heavy) plots. But on this centennial of Asimov’s birth, it’s worth considering whether his fiction still has something to say. Pervading his work is the illusory but captivating idea that there might exist scientific or mathematical principles that can reliably guide the future of humanity, rather than letting it spiral into chaos. So many popular science-fiction or speculative-fiction stories that have been given new life today are dystopian—for instance, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Michael Crichton’s film Westworld. In this light, Asimov is perhaps most useful as a counterpoint, a writer whose work resonates because it is out of step with the kind of future readers have become so used to imagining.

Although Asimov wasn’t a practicing scientist—he was booted from a tenured teaching position in biochemistry for failing to do any research—his training in the sciences informed his work. His positive visions of what’s to come are often grounded by carefully considered principles that recur throughout his writing. His I, Robot collection, for example, introduces readers to the Three Laws of Robotics (robotics being a new term that Asimov coined). The first and most important of these laws is that the machine can never harm a human, directly or indirectly. In the book’s first story, “Robbie,” a girl named Gloria becomes best friends with her robot nanny, Robbie. But because people don’t trust robots, Gloria’s parents get rid of Robbie, and it isn’t until Robbie saves Gloria’s life that her parents reinstate it.

Nearly every story in the collection follows a similar narrative: Robots start acting strange, which causes people to question the Three Laws, only to later discover that the machines are indeed safe. In the story “Liar!,” the robot psychologist Susan Calvin realizes that a machine that had been lying to her was really following the First Law and trying to protect her. In “Runaround,” a man places himself in harm’s way to fix a malfunctioning robot, knowing that the First Law requires the robot to save him. Time and again, the rules are vindicated.

These stories display a confidence in machines that might seem misplaced. In many robot narratives, from the earliest to the contemporary, these creations try to overthrow their human makers and recast the world in their own, sterile image. Even the 2004 I, Robot movie, which was loosely based on the collection, couldn’t accept Asimov’s premise and instead features bad robots trying to conquer the planet. Indeed, in an age where innovation often marches unchecked and the way people interact with technology is remade in every generation, the idea that humans could come up with infallible rules to keep our inventions from harming us seems far-fetched. Yet it’s this very point that makes Asimov’s stories attractive: Now, perhaps more than ever, people need something like the Three Laws to help manage our technological advances.

The Foundation series has an even more audacious premise than I, Robot, positing that the future itself is a solvable equation. The original trilogy, a series of eight linked short stories and novellas written in the 1940s, introduces psychohistory, a radical science for predicting the behavior of the masses. Psychohistory suggests that statistics can foretell the actions of large groups of people with such precision that one can plot the course of an entire civilization for thousands of years. Hari Seldon, the fictional father of psychohistory, establishes two planetary colonies, or Foundations, at opposite ends of the galaxy to create a new and gentler galactic empire that will replace the dying one. Because psychohistory predicts that the so-called Seldon Plan will not fail, Asimov’s characters cling to the plan with a belief that borders on religious. In the words of Hober Mallow, one of the Foundation’s mayors: “What business of mine is the future? No doubt Seldon has foreseen it and prepared against it.”

Psychohistory may seem more magic than science, and implicit in Foundation is an anthropocentrism that’s hard to swallow today. According to the series, humans will rule the galaxy. Humans can predict the future. The people of the elusive Second Foundation can control others’ minds. Even Seldon’s predictions tend to assume that heroes will arise at the right place and time to see the Foundation through each new crisis. Such bold confidence in humankind’s ability to manipulate history runs through several of Asimov’s works. In his novel The End of Eternity—often considered his best, featuring a protagonist with real conflicts and agency—humans have mastered time travel, and they defuse the tinderbox of history by preventing the development of the nuclear bomb. And with stunningly paradoxical hubris, Asimov’s short story “The Last Question” (his personal favorite) suggests that, really, it might have been man who created himself in his own image.

Readers nowadays probably think that human beings will sooner lapse into the repressive totalitarianism of George Orwell’s 1984—written in 1949, just as Asimov was wrapping up the original Foundation stories—or resign themselves to the smothering utopia suggested in Aldous Huxley’s 1932 classic, Brave New World, than create a benevolent empire. Asimov belongs to what is called the golden age of science fiction, which was spearheaded by people such as John W. Campbell, the Astounding Science Fiction magazine editor who wanted his contributors to write about human heroes and glorify scientific progress.

But by the 1960s, a new generation of science-fiction writers had tired of these tales of outer-space excess. One such New Wave figure, Michael Moorcock, said in 1963 that golden-age science fiction lacked “passion, subtlety, irony, original characterization … and, on the whole, real feeling from the writer.” Algis Budrys, in 1965, was skeptical of the golden age “implication that sheer technological accomplishment would solve all the problems, hooray.”

Sometimes, even Asimov himself agreed. By the end of the 1950s, supposing that the field “had passed beyond me,” he began writing nonfiction to get children interested in science and space travel. By the time he died in 1992 of complications from AIDS due to a blood transfusion (the cause of his death was kept secret for years), he had, by his own count, written or edited about 500 books spanning nearly every subject in the Dewey Decimal System, most of them nonfiction.

But readers keep returning to Foundation despite its datedness. The original trilogy is expertly plotted with gripping twists, such as the rise of the Mule, a mutant that threatens to throw the entire Seldon Plan into disarray. And as with I, Robot, the novels suggest that progress rests on predictability and human accountability more than on pure innovation. Recall that Foundation’s story begins with an empire in an advanced state of decay. Unfettered conquest spurred by technological prowess took people only so far. It is instead the invisible hand of psychohistory that lifts the galaxy from its lethargy, and only measure by measure, according to an agenda thoughtfully laid out long ago. Asimov makes readers wonder: Could there be laws that govern not just robots, but the fate of humankind as well? Unlikely, but the improbable is still seductive. And in these uncertain times, who doesn’t wish, on some level, that there were a plan for the universe after all?