Medical professionals battle virus misinformation online

by BEATRICE DUPUYDr. Rose Marie Leslie, a family physician at the University of Minnesota, is fighting misleading and false information around a virus outbreak with the very tool used to spread much of it: social media.

Leslie turned to TikTok, a platform popular with teens, to share her videos offering facts about the respiratory virus originating in China, which has so far sickened nearly 10,000 people. As of Friday, the videos had raked in more than 3 million views.

“The thing about TikTok as a platform is any video can go viral whether or not somebody is giving out factual information, and usually people don’t post where they get their information,” she said. “My goal is to be able to give the facts in every single one of my videos.”

From fringe groups pushing false — and dangerous — claims about how to prevent the virus to videos said to show people fleeing the outbreak or experiencing horrendous side effects, misinformation online is fueling fears and sowing confusion.

“I am overwhelmed by the volume of all the messages,” said Amelia Jamison, a University of Maryland faculty research assistant who has been keeping an eye on the deluge of misinformation around the virus. “So little information is being confirmed.”

Among the false information that has circulated around the virus: reports that the Federal Emergency Management Agency was proposing martial law to contain the spread; claims that drinking chlorine dioxide, a bleaching agent, would get rid of it; and graphic video footage that claimed to show an infected man vomiting blood on a train.

Advertising

On Wednesday, a video posted on TikTok — an app best known for lip-synching and amateur dance routines — showed a man in a lab coat who said he was testing two blood samples. One contained a bright red substance he identified as fresh blood and another, labeled “patient zero,” contained a purplish liquid. The video was intended to be satire but social media users linked it to the virus outbreak, which led to millions of views online, stoking fears that the virus was much worse than medical experts believed.

The spread of misinformation related to the virus has gotten the attention of key social platforms.

TikTok provided a statement to The Associated Press saying the platform does not permit misinformation that could cause harm to the community or larger public. Twitter announced Wednesday that it was adjusting its search function to provide authoritative health sources about the new virus. On Thursday, Facebook said it would remove harmful false and misleading content about the virus from the platform.

But health experts expressed concern that some of the false information around the virus may have already done damage.

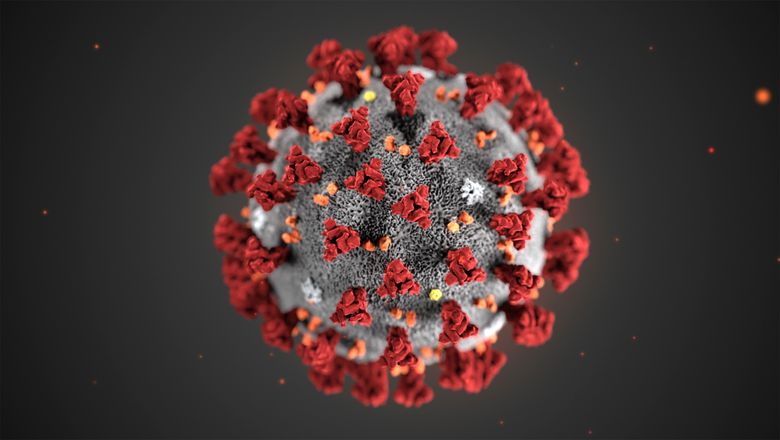

As the first case of the virus was reported in the U.S., anti-vaccine social accounts seized on the news to share the conspiracy theory that the U.S. government had known about the virus for years. As “proof,” many of them pointed to patents related to members of the coronavirus family of viruses, like SARS, which was at the heart of a previous epidemic. The new virus is also in the coronavirus family, but was not the subject of the patents.

Posts also attempted to link the emergence of the recent virus and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which invests in epidemic preparedness.

Advertising

“Sometimes in emerging infectious disease outbreaks misinformation may be more dangerous than the actual threat of the virus because it prompts people to take action that may have secondary cascading effects,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar who specializes in infectious diseases at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

One of the new battlefronts in the anti-vaccine movement is to stop the introduction of new vaccines by sowing doubt online, said Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development.

“They see a new disease coming along, they are very quick to say the disease is not real or it was invented by the government or pharmaceutical companies,” he said.

Anti-vaccine accounts shared similar false conspiracy claims during the height of the Zika virus in 2016.

Experts fear that the spread of misinformation online has led to a distrust of medical institutions and vaccines, feeding a resurgence of childhood diseases like measles. The CDC reported in 2000 that the U.S. had eradicated measles. Last year, the U.S. saw nearly 1,300 cases of measles — the largest number in 27 years.

“It’s one of the clearest consequences of this kind of misinformation,” Dr. K. “Vish” Viswanath, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health professor, said of the recent return of measles.

The World Health Organization on Thursday declared the virus outbreak a global emergency. Public health officials say that there continue to be many questions about the virus that need to be answered, including around how easily it spreads and its severity. This uncertainty leaves experts like Johns Hopkins Associate Professor Mark Dredze, who has published research on vaccine misinformation, worried that the misleading claims will continue to spread.

“It is much faster to make something up while waiting for information to come in,” Dredze said.

BEATRICE DUPUY