These Maps Paint a Dark Future for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge If Trump Has His Way

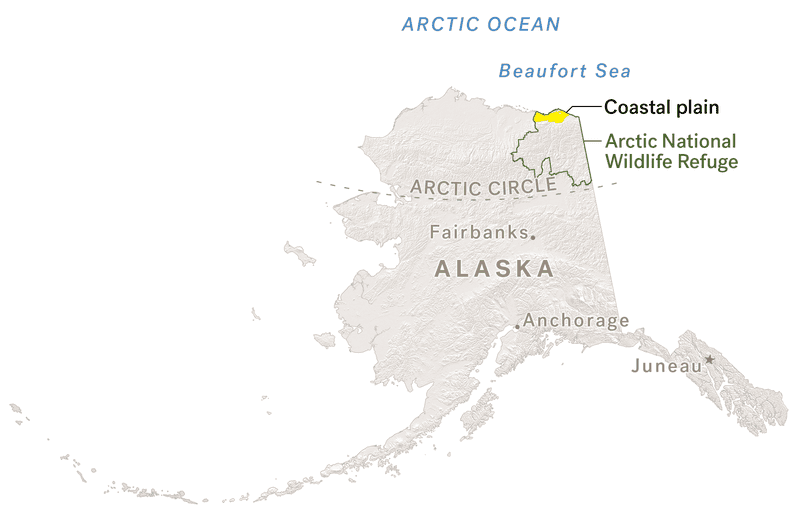

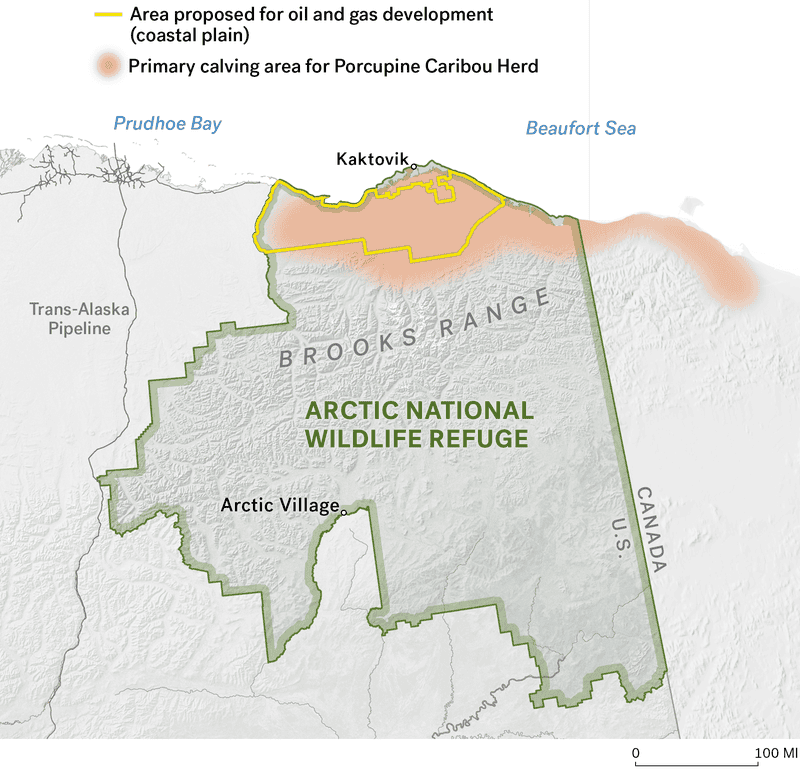

by Yessenia FunesThe Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is one of the last pristine landscapes in America. Tucked along the northern border of Alaska and Canada, the nearly 20 million acres of wilderness is home to a variety of wildlife species, including the Porcupine caribou herd, which visits the refuge’s coastal plain every summer where mothers give birth to their young.

President Donald Trump is obsessed with opening up the 1.5 million-acre coastal plain to oil and gas development, and many opponents are worried about what all this new infrastructure could mean for the caribou that spend their summers there. More importantly, the people of the Gwich’in Nation—who call themselves the “Caribou people”—rely on the Porcupine caribou for sustenance and culture. They worry about how development will impact their ability to hunt the animals for food and ceremony.

Even the Trump administration can’t ignore these potential impacts: The proposal’s final environmental impact statement released in September was clear that the well pads and pipelines that come along with oil and gas development may displace some caribou, which avoid the infrastructure. This reality is still a ways away as the Trump administration has yet to issue a record of decision on the project, Leah Donahey, legislative director at Alaska Wilderness League, told Earther. From there, lease sales must begin before oil and gas companies can come in with their trucks and pipes.

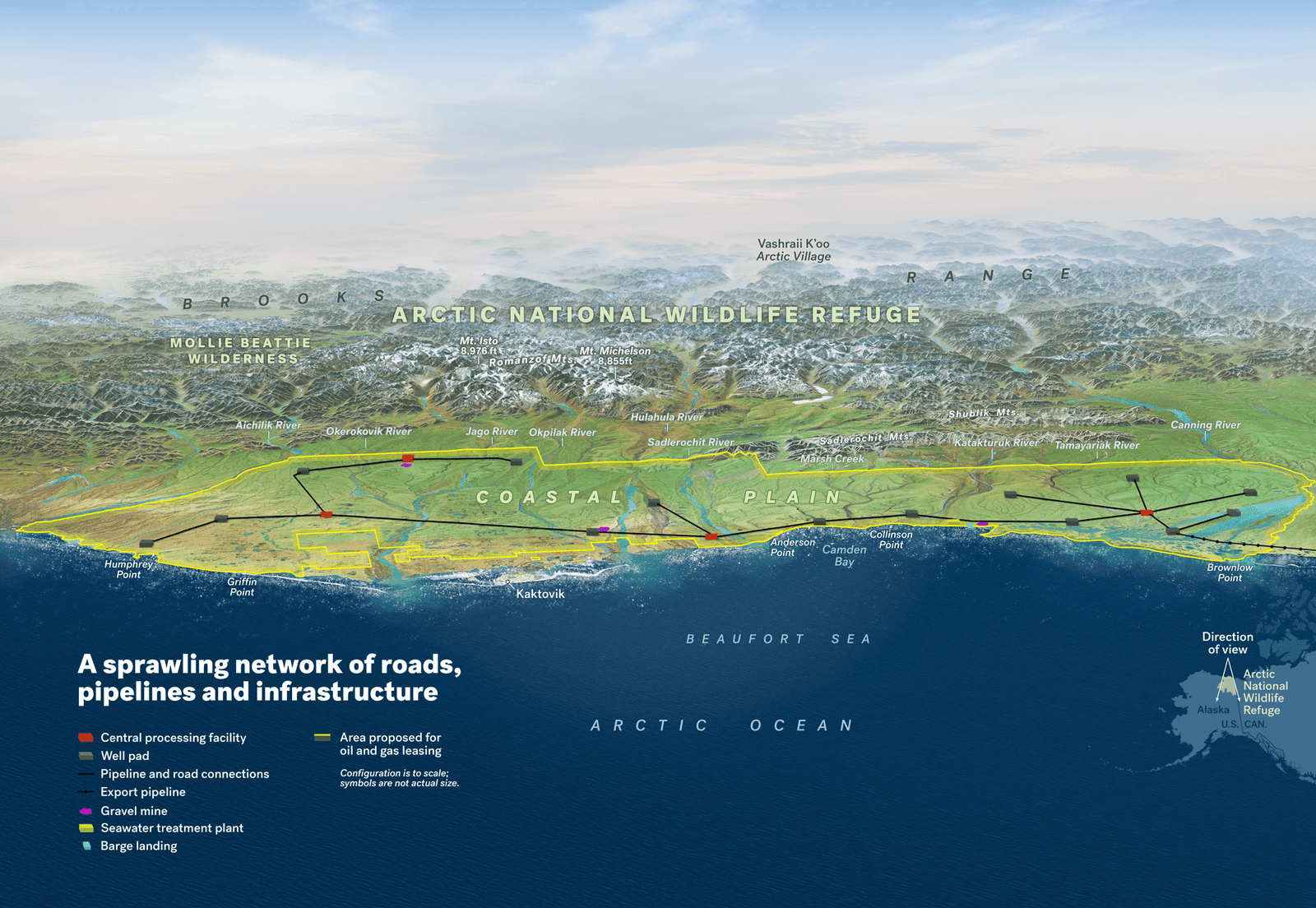

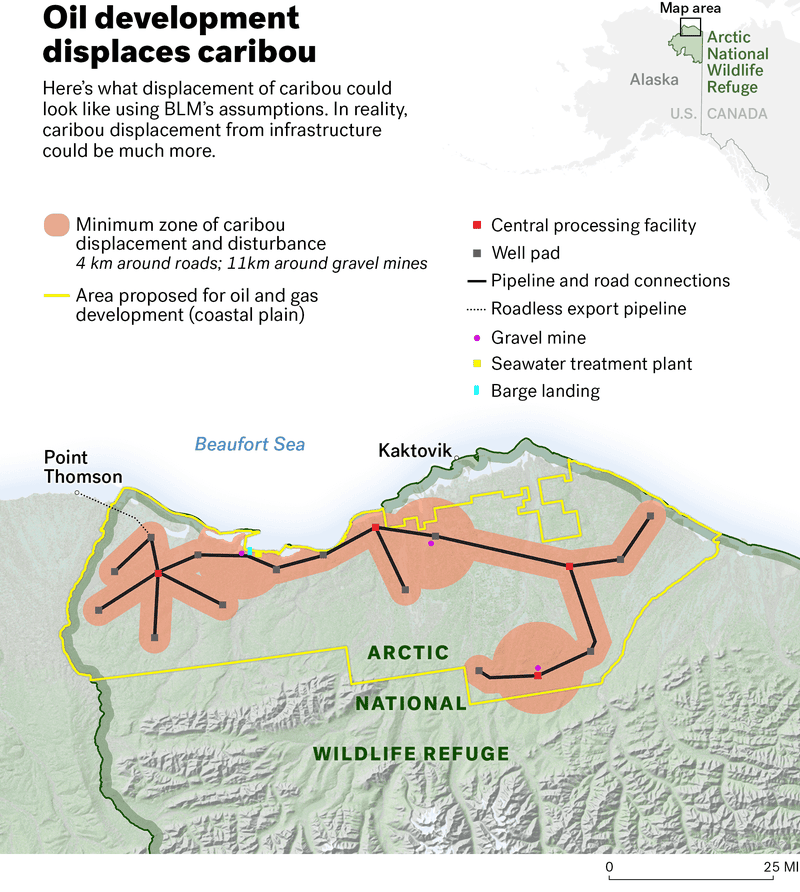

What would this actually look like, though? The Wilderness Society took all the data from the Bureau of Land Management’s “reasonably foreseeable development scenario” laid out in Appendix B of the environmental impact statement and illustrated how the fossil fuel industry could transform the coastal plain. The environmental group shared these hypothetical maps exclusively with Earther—and the results are deeply troubling. They show the infrastructure could span the entire coastal plain, stripping caribou of essential habitat.

Advertisement

The Porcupine caribou herd—which is some 200,000-caribou strong—flocks to the 1.5 million-acre coastal plain because the caribou have a clear view of any predators that come lurking around. Compared to the tundra caribou leave behind in summer, the plain is also largely free of mosquitoes that would otherwise terrorize their young. While mosquitoes may sound like a tiny nuisance, they pose a huge risk to young caribou. Besides blood loss, the bugs also cause young caribou to run around and lose crucial weight. As a result, the young caribou might not be able to make it through the harsh Arctic winter without the proper fat reserves.

For the Gwich’in, the coastal plain is known as The Sacred Place Where Life Begins. That’s why Bernadette Demientieff, the executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee that exists to protect the refuge from development, felt a wave of anxiety when she first looked at these maps. The Wilderness Society has worked closely with Demientieff and Gwich’in elders to make sure the maps reflect their cultural knowledge. However, the group also consulted academic research, ecologists, and an industry expert to convey this information as accurately as possible. Demientieff, however, didn’t need any of them to confirm what she already knows in her gut.

“I don’t need a Western scientist to tell me that oil and gas development is going to destroy the coastal plain,” she told Earther.

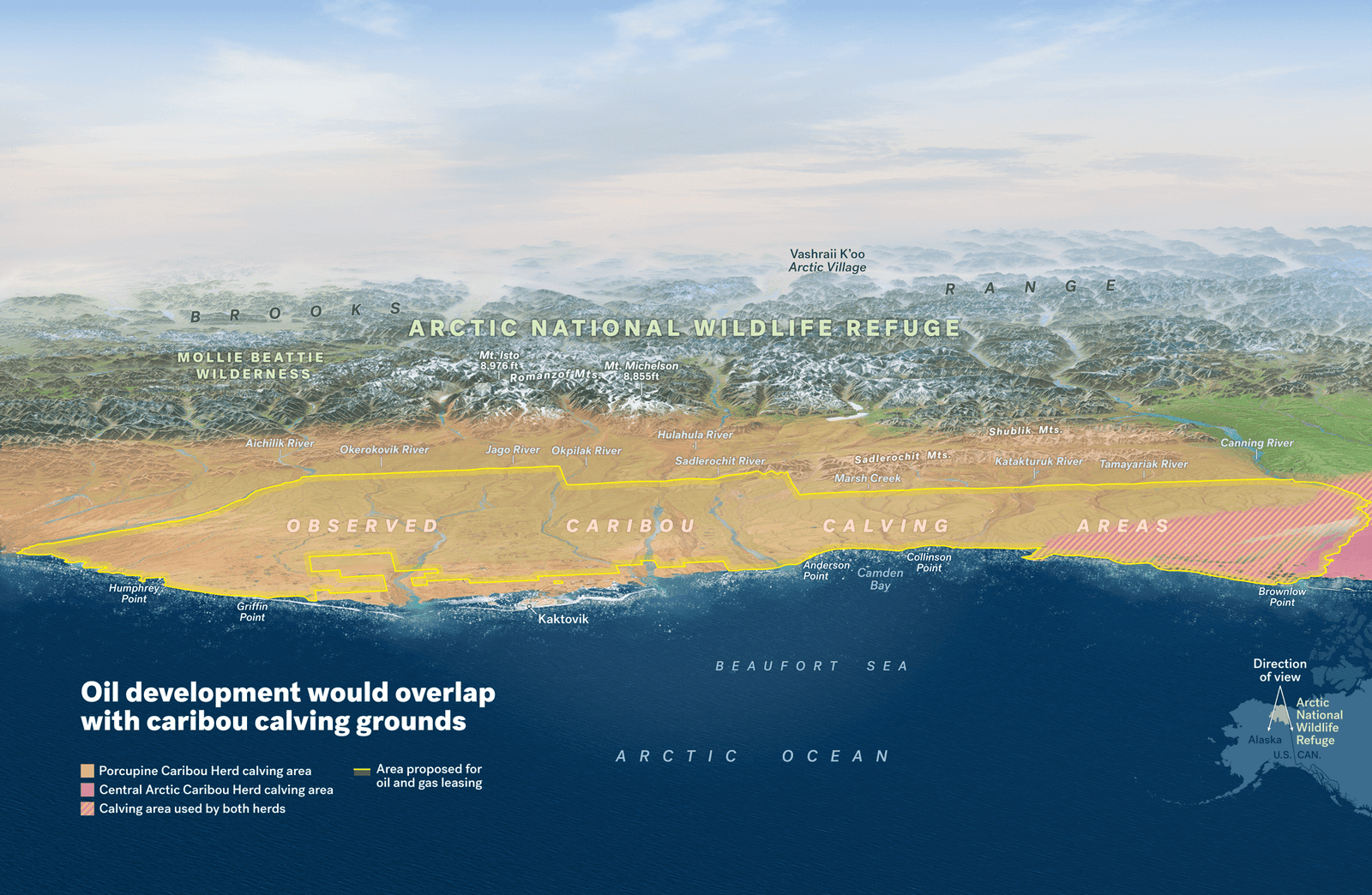

The Gwich’in are spiritually and culturally connected to the Porcupine caribou herd, and the map below shows how much of the coastal plain they use to calve. Even the Central Arctic caribou herd calves in the western portion of the coastal plain, which is on the right side of this image.

Advertisement

The development scenario the Wilderness Society has created here considers all of the government’s constraints around drilling. The location of the well pads and pipelines could very well change if and when extraction actually starts, but the team at the Wilderness Society created the maps using as much knowledge of regulations, terrain, and the location of where oil reserves are believed to be to create an accurate vision of ANWR if Trump has his way.

The Bureau of Land Management assumptions put forth in its environmental analysis are these maps’ main source of information. For instance, the number of satellite pads and miles of road used in these maps come directly from Table B-5 in the final environmental impact statement. However, the team attempted to make the layout as efficient as possible (as any company would likely do), so they included fewer pipelines than the government’s limit.

“There could be more,” Lois Epstein, the Arctic program director at the Wilderness Society, told Earther. “There could be less, too, but if we worked with BLM’s numbers, this is the kind of development that could occur.”

A major point of contention for opponents of the project is this notion that oil and gas development would leave only a 2,000-acre footprint on the coastal plaint. That’s the limit set forth in the 2018 tax bill that allowed this extraction to move forward in the first place. That might sound like a small impact on an area that stretches more than a million acres, but these maps show how this development can sprawl out across the landscape. Long fingers of pipelines spread out every which way, cutting the habitat apart. That makes the 2,000-acre footprint much more disruptive to caribou and other animals that currently move freely across the plain.

“The proponents of drilling say, ‘Well, that’s about the size of Dulles Airport,’” Epstein said. “They’re giving everybody the impression that it’s all in one place. That’s an absolutely misleading impression that no one should have because under the 2,000 acres, as it was defined by BLM and by Congress, you can have development sprawling throughout a 1.5 million-acre area .”

Scientists aren’t completely sure how the Porcupine caribou herd, in particular, would respond to this infrastructure during their calving and post-calving season because these animals have never been exposed, but the research out there isn’t encouraging.

Advertisement

The Central Arctic caribou herd has lived alongside oil and gas infrastructure for some 40 years now on Alaska’s North Slope to the west of the refuge. Yet despite decades to adapt, a study published last month in the Journal of Wildlife Management and authored by U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) researchers found that’s not the case.

The study relies on GPS collar data of 56 adult female caribou from 2015 to 2017 between June 1 and July 15, the time of year the caribou are most likely to interact with oil and gas infrastructure based on their patterns of habitat use. Previous research—most of which happened in the ’80s and ’90s—found that caribou avoided development by 2.5 miles, so the researchers looked at a 12-mile radius to not miss any odd behavior. This summer timeframe includes the calving, post-calving, and mosquito seasons for the Central Arctic caribou herd.

The researchers found that the largest disturbance happened during the calving period: Female caribou would, on average, reduce their use of habitat within 3 miles of energy infrastructure. During post-calving, that distance dropped to a little more than 1.2 miles and 0.6 miles during the period of mosquito harassment. These distances signal portions of habitat that caribou use half as much as researchers would expect, and the distances are rather alarming. What is also concerning, though, is that these animals haven’t gotten used to the development. These numbers are pretty much in line with studies from years past.

“What’s interesting about this is that we find the same result all these years later,” Heather Johnson, a research wildlife biologist with the USGS Alaska Science Center who authored the study, told Earther. “We don’t see habituation response over time during the calving season. Often, it’s assumed that animals will habituate to some kind of human disturbance factor over time.”

That being said, the Central Arctic caribou is not the Porcupine caribou herd. For one, the Porcupine caribou herd is nearly 10 times the size of the Central Arctic caribou herd. The Porcupine caribou also have a narrower piece of land on the coastal plain to give birth to their young than their Central Arctic pals. These differences make it hard to compare the two herds. While researchers expect the Porcupine caribou herd could behave similarly and avoid whatever fossil fuel companies build on their turf, they just can’t know for sure to what extent.

Based on what we do know, however, the Wilderness Society paints an image of the displacement the Porcupine caribou herd may face. The map below shows how large swaths of the coastal plain would be impacted. Tim Fullman, a senior ecologist with the group, took the lead on this portion of the research. He reviewed at least a dozen research papers, but no paper could fully answer the question of how this development would impact the porcupine caribou because they just haven’t faced this level of oil and gas disturbance yet. Which should be reason enough not to build it but alas.

Advertisement

Fullman worries that this lack of familiarity with these structures and the constant rumble of machinery could mean that the Porcupine caribou would make an even more concerted effort to avoid the infrastructure compared to the Central Arctic herd. Caribou are generally highly sensitive to predation when they’re calving. That’s probably why they avoid trucks and other equipment that can trigger a fear response.

The truth of the matter is that these creatures need closer scientific examination, especially with the recent push to expand oil and gas development in the region. There’s still a lot scientists don’t understand about caribou. After all, they live in the middle of nowhere and in some of the most extreme environments on Earth, making it hard for scientists to monitor them. Oil and gas infrastructure also poses a new threat to them that may lead to novel responses, which may explain why previous research has shown mixed results. For example, while one study in 2005 found that females were seeing lower birth rates near development than those farther away, another study in 2015 didn’t find those differences.

“Arctic caribou are still, in a lot of cases, really a mystery,” Johnson said.

The situation is much clearer for the Gwich’in, however. The coastal plain is sacred. The way they see it, no person should be there, much less an entire industrial sacrifice zone that will not only ruin the landscape but fuel the climate crisis. They’ve been doing all they can to prevent the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge from becoming the fossil fuel industry’s next playground.

While the Trump administration has tried to forge ahead and has spewed its usual climate denial to clear the way for drilling, there are some signs that the Gwich’in are finding allies in their fight to stop it. Goldman Sachs announced in December it would not finance any projects in the refuge. The Gwich’in also have a plan to turn to the international community for help. They plan to make the case before the United Nations Human Rights Council later this year to show that their human rights are being violated if the Trump administration’s plan is allowed to go forward.

Advertisement

“We will stand up to anyone who wants to go into this place,” Demientieff told Earther. “This is one of the last untouched ecosystems in the world, and it’s in our state, and we should take care of that.”