The Agony And The Ecstasy Of The Concord Grape

by Ryan F. Mandelbaum

In 1849, Ephraim Wales Bull strolled through rows of wild grapes in his Concord, Massachusetts, yard, each plant’s bare limbs spread out as if shrugging. After more than a decade experimenting with Isabella grapes that wouldn’t ripen outdoors and musty-tasting wild grapes that ripened too late, most people would’ve given up. Bull refused to.

On that September day, his patience was finally rewarded. Sprouting from a corner of his field’s poor, sandy soil was a vine with large, black fruit dangling from its arms. He popped one of the grapes into his mouth. It was sweet like candy.

Over the next century, Bull’s discovery, the Concord grape, would cross paths with everything from Little Women and World War I to the temperance movement and the American lunchbox. Today, the fruit behind grape juice might seem so ordinary as to be timeless, but its popularity was hard-won, the improbable result of a minister’s search for booze-less wine, Louis Pasteur’s fight against foodborne diseases, and, above all, an eccentric farmer’s stubborn search for the perfect grape.

People have been growing grapes for as long as they have been writing things down—longer, in fact. Scientists have uncovered chemicals left over from wines on Italian pottery dating back to the fourth millennium BCE, in an Iranian jar from a thousand years before that, and on earthenware fragments in Georgia a thousand years before that. Wine is mentioned in the Torah, the New Testament, and the Quran. Even the Mahabharata and the Epic of Gilgamesh discuss the grape-based drink.

But wine-making came relatively late to North America. Centuries after Europeans began colonising the continent, farmers in the United States still struggled to grow desirable grapes. Most of the country’s climate was ill-suited for prized European grapes. And wild American vines produced wines with a musty or “foxy” flavour. In 1854, Charles Mason Hovey, the editor of the Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs, described the sad state of American viniculture:

[As] the grape is esteemed,—that is, the superior varieties of foreign origin,—and as extensively as it has been cultivated in Europe, we have been and still are unable to grow it in our own climate, except by artificial means. Repeated attempts to raise it, both in a smaller and larger way, have all resulted in the same manner—complete and total failure, unless in the confined yards of our thickly-crowded cities, and its outdoor growth has been mostly abandoned.

In the early 19th century, farmers in the U.S. started hunting for suitable grapes by hybridizing wild grapes. Farmers in the South chanced upon a few better-tasting and hardier varieties, like the Catawba and Isabella, and later a farmer named Diana Ames Crehore discovered her namesake Diana grape in Massachusetts. According to Hovey, however, no variety met all of the needs of New England farmers, who hoped for a grape that would ripen in early September and produce a reliable number of large fruits. That is, until Ephraim Wales Bull came along.

Born in Boston in 1806, Bull originally trained to make and sell gold leaf. But he took an interest in horticulture and propagated seedlings in his Boston garden. After developing breathing problems, he left the city on the advice of a doctor, moving to Concord, Massachusetts, in 1836. According to the Milton Historical Society, horticulturists like Bull sprouted up throughout the region in the 1830s, the decline of agriculture in New England giving rise to “the affluent gentleman farmer,” who indulged in the art of growing plants.

Around this same time, writers in Concord like Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson were celebrating nature through the lens of transcendentalist thought. Emerson actually lived next door to Bull—according to the Smithsonian Libraries blog, he grew grapes in Bull’s yard—and the home of abolitionist philosopher Amos Bronson Alcott was just one more house down.

The Alcott residence would later become famous as “Orchard House,” where Amos Bronson’s daughter Louisa May Alcott wrote and set Little Women. All three structures still stand, and Bull’s house remains a five-minute walk from the childhood home of Alcott (who wrote about both neighbours and grapes, by the way.) Nathaniel Hawthorne’s son Julian remembered Bull as colourful local character “eccentric as his name”:

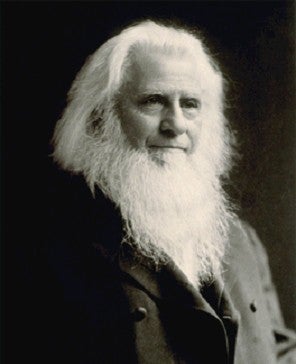

He was short and powerful, with long arms, and a big head covered with bushy hair and a jungle beard, from which looked out a pair of eyes singularly brilliant and penetrating. [...] He often sat with my father in the summer house on the hill, and there talked about politics, sociology (though under some other name, probably), morals, and human nature, with an occasional lecture on grape culture.

By Bull’s own account, he spent years trying and failing to cultivate Isabella grapes before turning to the wild grapes that grew in his Concord garden. Over the next decade, he grafted and planted hundreds of seedlings. Most of these grapes were no better than any other table grape. But on September 10th, 1849, a four-year-old vine produced a sweet, black, inch-wide grape—the only one of his seedlings to produce a grape superior to wild types. Perhaps, speculated Bull, the plant had crossbred with a nearby Catawba.

Sure that he’d struck gold, Bull hired an advertising firm to spread word of his Concord grape, selling vines for $US5 ($7) (equivalent to $US140 ($207) in 2020). The grape exploded in popularity across the northern United States and parts of Canada, and Bull amassed $US3,200 ($4,743) (about $US90,000 ($133,383) today) in his first year of sales. He also made a wine made from the grape for the Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs. Their committee found it to be “of a very excellent quality”—not bad for Bull’s first shot at vinification.

Meanwhile, the temperance movement against alcohol had been growing as part of the Second Great Awakening, an evangelical revival that began in the late 18th century. This movement aligned with the teachings of theologian John Wesley and associated early Methodist churches, which expressly forbade the drinking of alcohol, even during communion. But there weren’t many substitutes for wine: Grape juice stored at room temperature quickly ferments, and wasn’t available outside of the harvesting season. Some even boiled raisins to make temperance-friendly wine, according to an excerpt from an 1841 edition of The Primitive Methodist Magazine:

Our sister Ride purchased six pounds of good raisins, which cost two shillings and nine pence. She had them cut and put into an earthen vessel; poured on them as much boiling water as she thought proper; covered the vessel over, and set it warm, stirring it occasionally. And the next day, the wine was ready for bottling.

A Methodist named Thomas Welch set out to find a substitute. Born in England in 1825, Welch immigrated to the United States in 1834. He joined a Wesleyan Methodist Church as a minister in 1843, moved to Minnesota in 1856 to take up dentistry, and moved to a utopian “Temperance Town” called Vineland in New Jersey in 1865. There he joined the Vineland Methodist Episcopal Church as the communion steward. He was familiar with Louis Pasteur’s recently developed pasteurization process, which heated liquids to prevent the growth of microbes—including the yeast that turns sugar into booze. Welch applied the method to Concord grape juice, and in 1869, debuted “Dr. Welch’s Unfermented Wine.”

Welch’s grape juice was slow to take off at first, but as the temperance movement continued to gain steam, churches around the country adopted his Unfermented Wine for their own communions.

Welch’s has since grown into a large company owned by a cooperative of grape growers across the country called the National Grape Cooperative Association. It’s now as famous for fruit snacks and grape jelly as its juice. That jelly, originally known as “Welch’s Grapelade,” was first sold to the U.S. Army during World War I. After World War II, peanut butter was marketed as a spread that paired well with (the heavily advertised) Grapelade, giving rise to the now-ubiquitous peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

The Concord grape remains a popular cultivar across the northeastern United States (grape growers produced 400,000 tons of the fruit in 2018) and Welch’s brand grape juice, soda, and jelly are familiar sight in America. But the story of the Concord grape also demonstrates that something as mundane as supermarket jelly can serve as a kind of time capsule—in this case, one from an age that permanently shaped American thought, culture, and science.

For his part, Ephraim Wales Bull never found fortune with his creation, a victim of his own success. While his first crop of Concord seedlings sold swiftly, soon farmers throughout the region were growing (and selling) their own stock of the mighty grape. Bull died in 1895 a bitter, forgotten man. According to his own headstone: “He sowed; others reaped.”