Model Imaan Hammam stars in Alexander McQueen campaign

CAIRO: “How old were you when your grandmother died?” asks Egyptian filmmaker Marianne Khoury as we sit down in her Downtown Cairo office.

It’s the first among numerous other questions Khoury asks during our interview. She’s used to being on the other side of the recorder. This particular enquiry was triggered by Khoury’s latest documentary film “Ehkeely” (Let’s Talk) — a brilliant autobiographical meditation on the intricacies of motherhood, daughterhood, life, and death, among other sub-themes. As soon as I enter her office, I tell Khoury how her film has pushed me to reconsider my own family’s feminine history and to want to narrate it somehow. Blurring the line between documentary and fiction — and emerging, therefore, as what Khoury describes as a “family thriller” — the film had its world premiere at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, where it participated in the Official Competition, followed by a regional premiere at the 41st edition of the Cairo International Film Festival, where it scooped the Youssef Cherif Rizkallah Audience Award.

Khoury’s latest documentary film is “Ehkeely” (Let’s Talk). (Getty)

The film opens with an intimate conversation between Khoury and her daughter Sara, a Cuba-based filmmaker and student. This conversation emerges as a leitmotif throughout the whole film. Raw mobile footage gives way to a wide array of archival photos, video recordings, and extensive interviews done by Khoury with multiple family members over the years. From Cairo to Cuba and beyond, the film meshes these different, rather raw, formats to offer a fresh and novel take on family storytelling.

While the film can be seen as an engaging account of a cosmopolitan Egyptian family that loved and lived for cinema (Khoury’s maternal uncle was the acclaimed filmmaker Youssef Chahine, with whom Khoury worked for years), the film’s real power lies in how it chooses to reveal a lesser-known story — that of the family’s “feminine line,” which may have been overshadowed by the family’s male figures. This “feminine line” begins with Khoury’s grandmother Marika, and moves to Iris (Khoury’s mother), before reaching Khoury herself and finally Sara.

The film opens with an intimate conversation between Khoury and her daughter Sara, a Cuba-based filmmaker and student. (Supplied)

“For years, I was going around in circles not knowing what story I wanted to tell,” says Khoury, whose directing repertoire includes “The Times of Laura,” “Women Who Loved Cinema,” and the award-winning “Zelal.” “I knew I wanted to make a film about my mother. But I couldn’t bring myself to revisit the [family] archive because I was still coming to terms with her passing.

“My mother passed away in 1989 while I was still pregnant with my son,” she adds, pointing to the concurrence of life and death at this particular moment.

“I could not navigate my grief right away because I was busy looking after my kids. Flash-forward years later, I finally began to ask myself what I was doing and where I was (headed).”

Marianne Khoury’s late mother held hands with Egyptian actor Omar Sharif. (supplied)

That Khoury eventually felt ready to make a film about her mother was due in great part to her conversations with Sara, some of which are sampled in the film. These extended conversations, Khoury stresses, constitute a normal aspect of their relationship both on and off camera.

“One particular conversation with Sara became the film’s backbone, after which I knew I had a film and began to map out its sequence,” Khoury explains.

She proceeded to revisit the family archive she had amassed over the years — a hefty task that explains why the film took “ages” to finish.

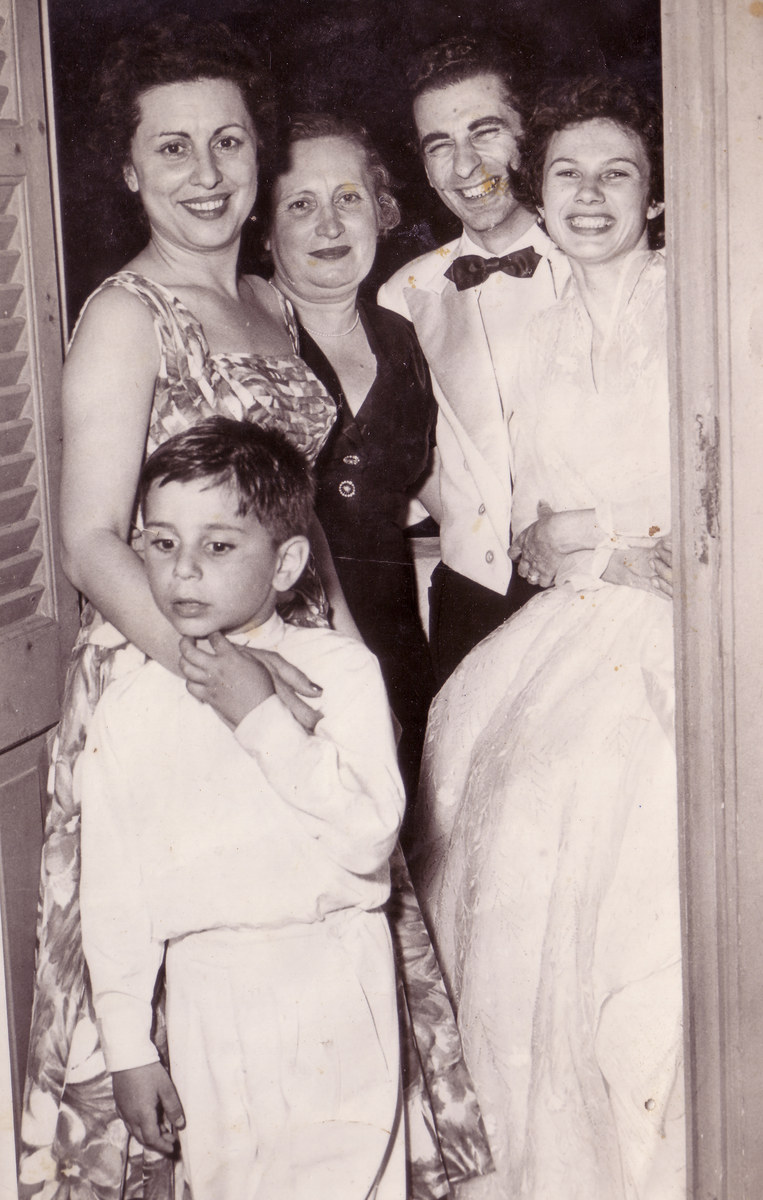

Egyptian filmmaker Youssef Chahine with his mother, Nona or Marika. (Supplied)

At the heart of this archive were everyday moments: the family at a Christmas dinner, or one-on-one conversations with Chahine, Khoury’s brothers, or aunt.

This constant filming of the “ordinary,” Khoury says, has always been an integral aspect of her life, especially as “a very thin line separates cinema from reality in my life anyway.”

According to Khoury, she chose to trace this feminine line in her family’s archive “because I relate to it.”

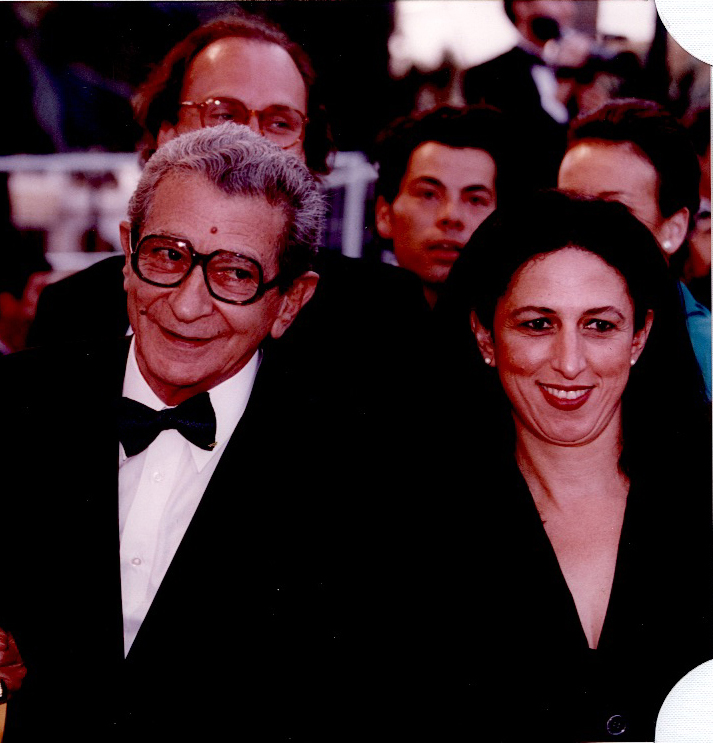

Khoury’s maternal uncle was the acclaimed filmmaker Youssef Chahine. (Supplied)

“As I told Youssef Chahine in one of the interviews sampled in the film: I pursued this project because I’m a woman, mother, daughter and sister. And I need to talk about these things; the things I know,” she explains.

But telling the story was far from easy — especially when another member of Khoury’s family, namely Chahine, had taken part in this very same exercise. Chahine had portrayed the women of his family in films including “Iskindiriyya Leh?” (Alexandria, Why?) and “Hadouta Masreya” (An Egyptian Tale).

“It was very difficult to try and get Chahine to talk. He didn’t want to talk (about family members) — and even asked why I bothered with knowing (more about their lives),” says Khoury. “He was convinced he had said everything there was to say about my mother and grandmother in his films.”

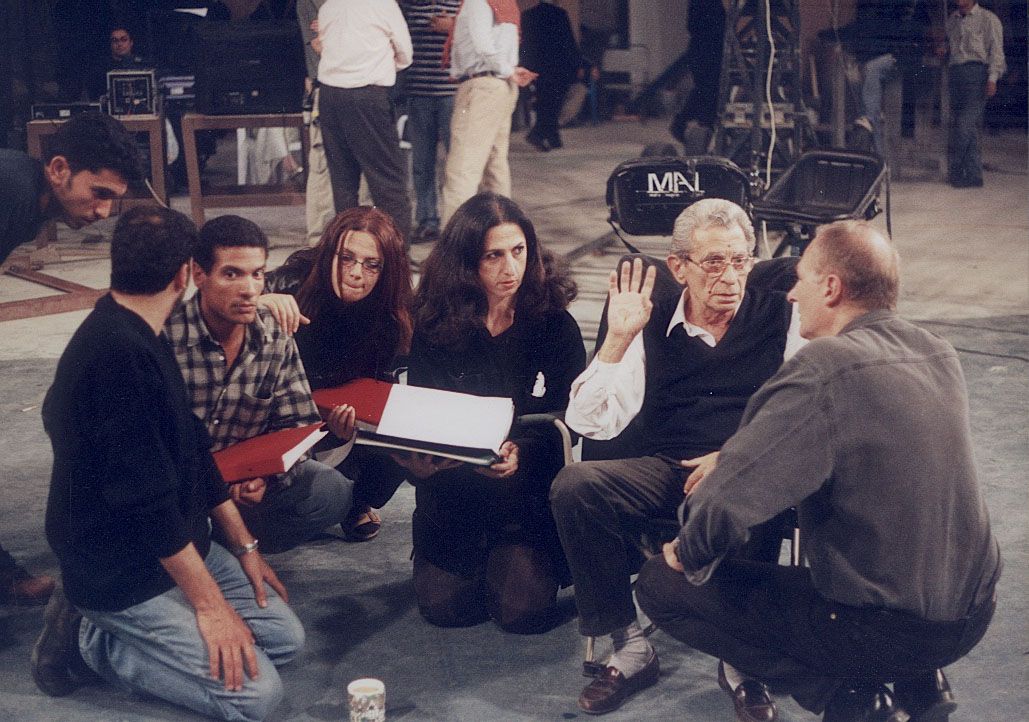

Khoury worked with Chahine for years. (Supplied)

But Khoury saw her family’s female members differently and was adamant that she should tell their stories from her point of view. In one instance, she included snippets from Chahine’s films into her own to highlight this tension between “how Chahine portrayed these women and what I tried to say about these very same women in my film.”

At the heart of Khoury’s narration of this feminist history lies her desire to understand her position as both daughter and mother concurrently.

“There was a moment in the film where my aunt informed me that my mother wanted to abort me. I felt a sense of contentment at first, because I could finally trace my constant melancholia back to something,” explains Khoury. “But it wasn’t long before I decided this was an all-too-easy conclusion: to attribute my perpetual feeling of melancholy to the fact that my mother didn’t want me. After all, she took care of me and loved me the way she could love.”

Chahine’s wedding. (Supplied)

Khoury knew she had to dig deeper, and one way she has done that in the film is by humanizing her mother and revealing how the latter grappled with her own life-long melancholia.

At the same time that Khoury was exploring the nuances of her relationship with her late mother, she was also responding to her own daughters’ questioning of their own complex relationship.

“Sara began asking herself (big) questions very early on. There’s always this element of ‘mirroring’ in our relationship. She asks me questions; I think about them and answer her back,” she says. “You could say that this wasn’t just a film. It was more of a healing process for both of us.”

At the heart of Khoury’s narration of this feminist history lies her desire to understand her position as both daughter and mother concurrently. (Supplied)

And therein lies the film’s power: It tells the truth. It gives its characters the space to heal difficult relationships. “Life is all about contradictions,” Khoury says. “And this is what I finally understood after going through the whole process, that all relationships are essentially complex.”

The trick, according to Khoury, is to “find yourself amidst this complexity.”

Perhaps it is this gripping honesty that gives the film its enduring magic. Since its Egypt premiere in mid-January, the film has garnered critical acclaim, with some viewers reportedly returning for multiple viewings. Clearly, the deeply personal subject matter has struck a universal chord.

“I am very happy. I cannot believe the extent to which the film has impacted those who’ve seen it,” Khoury says. “The film confirmed to me that what I like is right. I knew I wanted to make this film the moment I saw a (similar) film about a Lebanese family some 30 years ago. I loved this film the same way people love my film now.”