All Humans Are a Little Bit Neanderthal, According to New Research

by George DvorskyWe’re all a little Neanderthal. That’s the conclusion of a study that used a new statistical technique to revise estimates of the degree to which modern humans have retained Neanderthal DNA. The research suggests that even people of African descent have Neanderthal heritage, something that was previously in doubt.

Research published yesterday in Cell has identified significant traces of Neanderthal ancestry in African populations. The new paper, co-authored by geneticist Joshua Akey from Princeton University, claims that “African individuals have a stronger Neanderthal ancestry signal than previously thought.” The finding complicates our understanding of human origins and the migration patterns that contributed to the makeup of our species.

“So far, estimates of Neanderthal ancestry in Europeans and Asians have used the assumption that Africans carry no Neanderthal ancestry, although we knew that that was not strictly true,” Svante Pääbo, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, told Gizmodo. “We knew there was some in Africans,” the result of a supposed migration event that happened a long time ago, said Pääbo, who wasn’t involved with the new research. The new paper affirms these assumptions, suggesting interbreeding events that date back as far as 100,000 to 200,000 years ago.

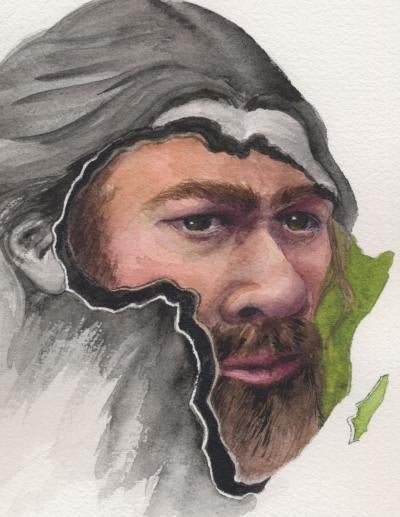

Illustration: Matilda Luk, Princeton University Office of Communications

Investigations into the Neanderthal genome, which was sequenced in 2010, have suggested that anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) of Eurasian descent have retained around 2 per cent Neanderthal DNA. This was taken as evidence that modern humans interbred with Neanderthals as they spilled out of Africa, entering into the Middle East, Europe, and Asia between 80,000 and 50,000 years ago.

At the same time, palaeogeneticists struggled to detect traces of Neanderthal DNA in African populations. This lack of evidence jibed with the conventional narrative, that modern humans who left Africa and subsequently interbred with Neanderthals never returned, or at least not in any meaningful way that impacted upon human evolution. The new research now upsets this notion, offering evidence to suggest there’s more Neanderthal DNA in African people than previously assumed. What’s more, the evidence suggests multiple interbreeding events occurred between humans and Neanderthals – including episodes that date back to over 100,000 years ago.

“This is additional evidence that modern humans, or ancestors of modern humans, left Africa several times and mixed with Neanderthals,” said Pääbo. “Those modern humans are not ancestors of present-day humans in Eurasia. They were at least partially assimilated into Neanderthal populations,” and this “happened more than 100,000 years ago.”

There are two primary reasons why it’s been so difficult to find Neanderthal sequences in African individuals. The first reason is rather simple, and even a bit infuriating: the unwarranted assumption that very little Neanderthal ancestry should be found in African individuals.

The second reason has to do with the methods used by geneticists, but it’s directly related to the first reason.

“Previous methods to find Neanderthal sequences in the DNA of modern humans all used a ‘reference’ population thought to contain little or no Neanderthal ancestry, and this was always an African population,” explained Akey in an email to Gizmodo. “The reason a reference human population was used is that modern humans and Neanderthals share a recent common ancestor and many places in our genomes will look Neanderthal-like just because of this shared evolutionary history. Using a reference population allows you to subtract out this signal of shared ancestry and identify sequences that were inherited because of admixture [interbreeding].”

Trouble is, this reference population, i.e., genomes from African individuals, produced biased estimates of Neanderthal DNA among modern human populations. To correct this bias, Akey and his colleagues devised a new statistical method, called IBDmix, which did not require a reference population, while still allowing for searches of Neanderthal ancestry in African individuals, which hadn’t been done before.

IBD stands for “identity by descent,” and it flags identical sections of DNA that are present in two different individuals. These shared segments are taken as evidence of a shared common ancestor; the longer the segment, the stronger the supposed linkage to a common ancestor.

This reference-free method applied known characteristics of Neanderthal DNA, such as the prevalence of alleles (mutations) and the length of IBD segments, to identify common ancestry tied to ancient interbreeding events. With this method, the team identified Neanderthal DNA in Africans for the very first time, while also providing revised estimates of Neanderthal DNA in other populations.

“This new approach allowed the authors to evaluate the possibility of the presence of Neanderthal genetic material in African populations – something that was ‘hidden’ before due to assumptions of the methods previously used, which considered African populations not to have any such admixture with Neanderthals,” explained palaeoanthropologist Katerina Harvati from Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen. “The surprising result was that, indeed, there was a considerable Neanderthal contribution to African genetic material, which was greater than previously suspected,” said Harvati, who was not involved in the study.

On average, the amount of Neanderthal DNA was found to be around 55 million base pairs per person among Asians, 51 million base pairs per person in Europeans, and 17 million base pairs per person in Africans, though these amounts will vary from individual to individual. In terms of the overall proportion of Neanderthal DNA, Akey said that’s “a bit tricky to define because we can’t analyse all parts of the genome due to technical limitations,” but a rough approximation suggests 1.8 per cent in Asians, 1.7 per cent in Europeans, and 0.5 per cent in Africans.

“I think the most interesting finding of our work is that it highlights that modern humans and Neanderthals were interacting for hundreds of thousands of years and that there were many dispersals out of and back into Africa,” said Akey. “It reveals a more nuanced and complicated history than previously recognised and shows that the legacy of gene flow between modern humans and Neanderthals exists in all contemporary individuals today.”

Indeed, this research suggests modern humans, after interbreeding with Neanderthals, migrated back to Africa, but it also points to ancient mating episodes between the ancestors of both modern humans and Neanderthals perhaps as far back as 200,000 years ago, a claim that’s supported by other research.

“This article joins several studies published recently in pointing out the importance of dispersals, back migrations, and interbreeding among human lineages and populations, both in the Pleistocene as well as more recently, and reinforces the view that human evolution was more complex than previously thought,” explained Harvati. “It also supports previous findings of an ancient interbreeding event, before 100,000 years ago between early modern humans and Neanderthals.”

Harvati said this was suggested by previous palaeogenetic evidence shown in several different studies, as well as the fossil record.

“Early modern humans are known to have dispersed in an early Out of Africa migration, as early as approximately 200,000 years ago, as recent fossil discoveries in Greece and Israel indicate [see here and here], and would have had the opportunity to meet and breed with Neanderthals,” said Harvati. “The authors even hypothesise that there might have been multiple Out of Africa dispersals and interbreeding events, only some of which can be detected with their current datasets and methodological tools.”

Interestingly, a sister group to the Neanderthals, the mysterious Denisovans, were likely not part of this equation. Denisovans branched off from Neanderthals around 400,000 years ago and lived in Asia for hundreds of thousands of years. It is “becoming more and more clear that Neanderthals were in genetic contact with populations in Africa multiple times during their history,” which stands in contrast to the Denisovans, “who were more isolated from Africa,” said Svante.

In terms of limitations, Akey said his team only analysed genetic data from a small number of African populations and that “a better sampling of African genetic diversity will be necessary to understand patterns of Neanderthal ancestry across Africa.” Also, by virtue of how the new technique works, the researchers are not able to detect genetic sequences potentially inherited from unknown hominin lineages.

Harvati said many questions still remain, including the genetic contribution of archaic African lineages.

“Since we don’t have palaeogenetic evidence from African fossils, this is difficult to evaluate and remains a complicating factor, as retention of archaic African genetic material, as well as interbreeding between early modern humans and archaic lineages in Africa itself has also been postulated,” said Harvati.

No doubt, the study is raising important new questions that future researchers will have to tackle. As time passes, and with each new scientific breakthrough, our evolutionary history is somehow becoming clearer but also considerably murkier. While tempting, simplistic explanations are almost never correct. Our story is as complicated as it is fascinating.

Featured image: Neanderthal Museum, H. Neumann