Sundance 2020

Saudi Runaway: behind a suspenseful and courageous documentary

In an audacious new film, a young woman secretly documents her preparations for escape from an arranged marriage on her smartphone

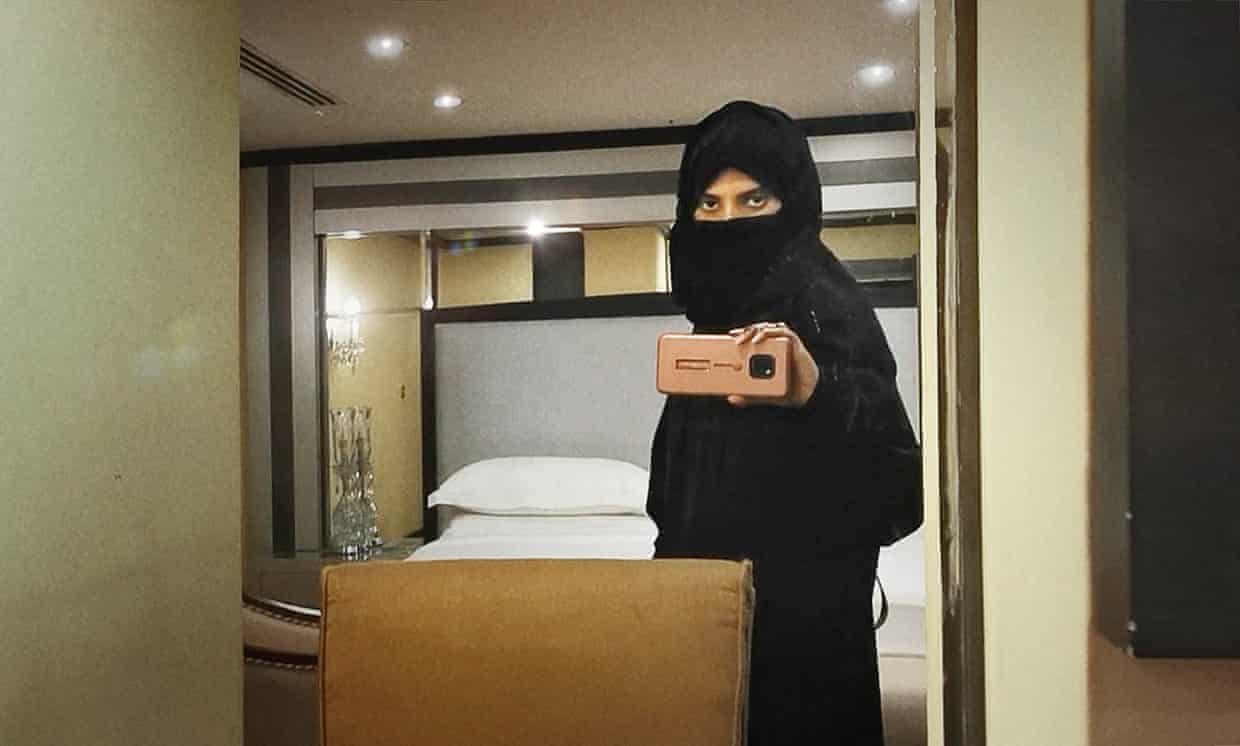

by Adrian HortonThe first time Muna, the protagonist of documentary Saudi Runaway, turns the camera on herself, you can’t see her face; she’s shrouded by black cloth, the typical fashion for a woman’s public outing in Saudi Arabia, a country which maintains, according to Human Rights Watch, a stance of unrelenting oppression. When she holds her phone up for what would be the social media standard mirror selfie, her reflection is doubly obscured – both her entire body and her phone are under wraps. Muna films surreptitiously, either from under her niqab, in public, or posing as a typical phone-obsessed millennial at home. The videos make her case: faced with an impending arranged marriage and a life constrained by Saudi Arabia’s male guardianship system, she plans to flee the country on her honeymoon.

Over the course of five weeks in 2019, Muna records the nerve-racking and mundane run-up to her escape through the tunnel-vision portal of her smartphone, from booking flights to wedding dress shopping with her family (all faces other than hers are blurred). The resulting film, directed by Susanne Regina Meures, a Swiss-German film-maker to whom Muna sent her videos, reveals a journey that can be harrowing, in the lengths it takes to mask one’s pain, conflicted (“There are things I like about this country,” she says while walking through an abundant, bright market) and above all, courageous. Like Midnight Traveler, another recent documentary filmed entirely on one family’s smartphones, Saudi Runaway is most gutting in its unvarnished, quiet moments: a conversation with her grandmother, in which she advises Muna “be obedient and everything will be fine”; shooing her brother out of her room, lest he catch on to her project; holding the camera steady toward the bathroom mirror with one hand and wiping away tears with the other as she listens to a raw voice message from her mother.

Meures, who had previously filmed in Iran, had long been interested in Saudi Arabia but was repeatedly denied a visa to the country. At the beginning of 2019, however, there was a new wave of Saudi runaways – young women escaping strict male guardianship and claiming asylum in other countries – and “the whole topic came back to my attention”, Meures told the Guardian. “It’s time to give a voice to these women,” she thought. “But I had to find a way to actually get into the country without actually getting into the country.”

Meures got in contact with a Saudi activist in Europe who ran a group chat with numerous Saudi women contemplating escape. He posted for Meures in Arabic – “basically, I wrote that I’m looking for someone who’s planning on leaving the country in the near future,” said Meures. More than 30 women expressed interest, but none felt comfortable showing their faces on camera – “understandable”, said Meures, as subversive exposure “could possibly be dangerous”; the government’s advances for women in the last year – allowing them to obtain driver’s licenses, renew passports over age 21 without male permission, or register their children for civil statuses – have been coupled with a crackdown on dissidents and human rights activists.

Still, she got a message from Muna, and “that was it”, said Meures. “Day No 1, she was like: ‘I want to make this film. I need to show the world what is going on.’” The next day, Muna started filming and uploading the videos to Meures, who saved them on a hard drive. Using encrypted messaging apps, the two chatted for five to six hours each day, going over the footage, discussing form and content (a shot of birds behind a dirty window screen is both a filmic detail and evocative of a prison, for example).

From the start, they were working under tight constraints; Muna was only five weeks away from her wedding, and she knew, according to Meures, that her honeymoon “would be her absolute last chance to leave the country”. The tight timeline gives the film a claustrophobic, nervous feel; as the date approaches, the suspense is palpable and intense. Given that she’s staying in a hotel room with her husband, can she get on the plane? And given a last-minute twist delivered by her mother, will she?

Throughout the film, Muna reflects this turmoil quietly on her face – in silent tears, a blank tilt of a head as if taking a makeup selfie, a hard stare as she peers beneath her covering in the mirror. Muna’s gift, according to Meures, is that she’s “able to take us into her world, but you never have the feeling of her acting” She has a rare skill for crying and filming herself at the same time; under emotional pressure, her hand is steady. “She was just so incredibly courageous – that was something that surprised me every single day again,” said Meures. “She has an amazing mix of stubbornness and courage and the bravery of standing up and actually doing something.”

Escape, said Meures, is “I think something that is discussed amongst young women, especially in [Muna’s] class”. From an outsider’s perspective, “seemingly at the moment, the crown is relaxing many of the very strict laws … but as a matter of fact, the majority of society is deeply conservative and the majority of young women are living through exactly what Muna is living through.” The goal, Meures said, is to offer “a more multifaceted image of Saudi Arabia”.

For Muna, that image takes on the burden of building a case for leaving – a radical act of personal and political will made shot by secret shot. “I want you to understand our situation,” she says at the beginning, cloth flitting over her camera lens as she walks the streets of Mecca. “I’m recording not only for this documentary. These records will also be my evidence.”

- Saudi Runaway is showing at the Sundance film festival and will be released at a later date