Kleber Mendonça Filho on ‘Bacurau’ and How the Brazilian Government is Destroying Culture

by Rory O'Connor

With three features to date, Brazilian filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho has distinguished himself as one of the most eclectic voices in world cinema. His 2012 debut Neighbouring Sounds took elements of surrealism and the thriller genre to talk about the anxieties of an upper-middle-class community in his home town of Recife. Aquarius, his 2016 follow-up, caused a small storm at the Cannes film festival when Filho and his team stood in protest against his country’s political turmoil while walking the red carpet. The incident began what has become an ongoing rift with Brazil’s increasingly rightwing authorities.

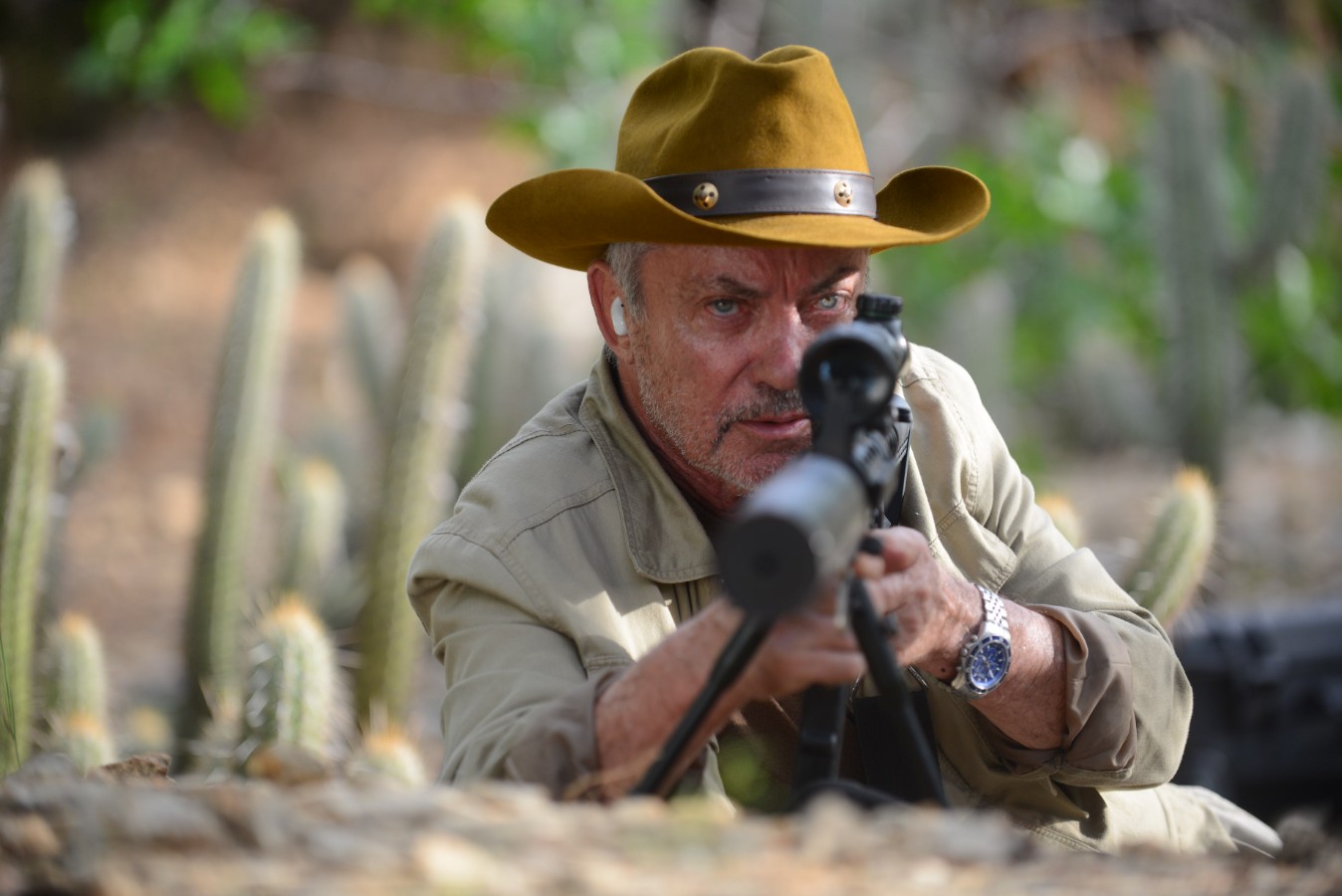

Filho and co-director Juliano Dornelles were back in Cannes earlier this year with Bacurau, a provocative and scarcely definable film about a small farming community in Brazil’s Sertão region that become the targets of a heavily armed group of foreign hunters. It’s the director’s first real genre outing but, as that synopsis might suggest, it is a film with no fewer socio-political concerns than his previous two. We caught up with the filmmaker at the Marrakech International Film Festival to discuss his mainstream influences, capturing a class divide, and the culturally disastrous decisions of the Brazilian government.

The Film Stage: At the beginning of Bacurau you see these distinct titles and hear this distinct music and you immediately think: John Carpenter. Then later on, of course, these western elements come into it. Did you set out to make an homage?

Kleber Mendonça Filho: Yes, because I think it’s only natural when we finally get to do something—in my case films but you could be a writer writing a book—you keep going back to the things that made you fall in love with the medium in the first place. So I was a little kid in the ‘70s and a teenager in the ‘80s and, of course, it was a time of going to the cinema in big movie palaces; of VHS; of watching films on television. A lot of what I think are great American films of the time made me what I am today. And at 14 I began to watch non-American films and I discovered another page, in my formative years. But the great films of the ‘70s—shot in Panavision, in 35mm; by Carpenter, Camino, Romero, and De Palma—they made me want to make films. And I think I’m very lucky. My generation was very lucky because those were commercial films. It’s the kind of thing you would see in a commercial cinema.

They were part of the culture in a different way.

Yes, it wasn’t a cinematheque kind of programming or a film festival with classics. These were commercial films. And I think—I don’t want to sound like an old man—but today, mainstream cinema, in my mind, is not as good. It doesn’t mean that we don’t see good films; we do, but not in a matter of fact kind of way. You know, “What’s on? Oh, a new Cronenberg, it’s been on for four weeks.” [Laughs]. Like going to see The Fly. It’s a 20th Century Fox film, a studio film. So it’s completely different.

That’s kind of a perfect movie, I think.

Masterpiece. And then you see that on a Sunday afternoon, in a 1,000-seat cinema and you go: This is amazing. And that was a commercial film. So I miss that normality of wonderful cinema.

You’re clearly a very eclectic filmmaker. When you’re sitting down to write a new film is it important that you go in a totally different direction to the previous one?

I think each film demands new attention. Like, I don’t know, you go out at night and you have to decide what you’re gonna wear, depending on the weather and the situation, especially here in Marrakech. Like some night it’s gonna be tuxedo but tonight, for The Irishman, it’s just gonna be this. So I think for each film, it’s almost like you get a letter from the film saying I need this, this, and that. And Bacurau is my first openly genre film. Aquarius and Neighbouring Sounds, they were social realism but then they had some sparks of something else–maybe thriller?–but I didn’t really leave the road like in Bacurau. Bacurau kind of goes woah, goes away, which is very liberating.

Are you looking forward to The Irishman?

Very much so. I saw 45 seconds at home before I came to Marrakech and then I stopped–some hospital scene. It’s another thing, another strange time. I have to make an effort and run and see a very rare screening of a Scorsese film because it is actually in 150 million homes right now. So it’s a very strange time.

Same with Marriage Story.

Yes. Shot on film, projected on DCP; a few screenings around the world and then 150 million homes. And they’re buying the Paris Theatre in New York. What?! It’s fascinating.

Do you often catch mainstream movies?

I want to take my two 6-year-olds to see the new Star Wars at Christmas. I saw Joker. Yeah, I saw Tarantino in Cannes, which I think is a very unusual film for a big studio to spend $150 million on, which I think is excellent. So cinema still manages to find strange ways of surprising you.

There is this recurring trope of people in rural or less privileged or working-class situations being depicted as stoic and quiet; even angelic in a way. Was Bacurau a reaction to that in some sense?

Bacurau is a reaction to the way a certain kind of people are portrayed everywhere. It happens also in the United States, but in Brazil by big media. And we happen to come from the region which is often portrayed in the way we dislike. We come from the Northeast of Brazil, so the whole media circus in Brazil is centered on the Southeast region; Rio, Sao Paolo. It’s a similar thing in the United States when New Yorkers say the “flyby” states. It sounds kind of aggressive. So Brazil has this thing where characters from the Northeast are often exotic and kind of funny—and funny because they are ignorant and they lack sophisticated words. It’s just a horrible cliché and we thought that we should write this really great community where people make sense and they are normal and they are wonderful and interesting and they have culture; they understand history.

And that’s one of the biggest hits within the film in Brazil. People were just completely surprised by the way the film does what it does. And of course, we did not ignore some of the very unpleasant national tensions that exist in Brazil. There is a kind of what I call a force field around the northeast which comes from economics, racism, and geography and that is addressed in the film. Particularly in the scene with the meeting with the foreign invaders when the two Brazilians try to pass as one of them and they say, “What do you mean? You’re not white. She could be Polish, she could be Italian, but her lips give it away…” It’s a very unpleasant scene but that really hit a nerve in Brazil.

I read that a rare downpour hit the region during the shoot. How much did that bleed into the mood of the film?

That offered more logistical problems than artistic inspiration. The only artistic thing was that we decided to embrace it and show the Sertão after rain. And that’s another thing that goes back to the southeast/northeast thing–films only show the Sertão dry; as in barren. Completely dry. So some films have actually been canceled or moved to some other region because it rained and it wasn’t the image they wanted; this classic image of the Sertão. So when it rained we thought, that’s not a problem. The Sertão can be rain; let’s shoot it the way it is. So that’s another decision that ends up being a political decision because it was ridiculous to run away from reality just because the classic cinematic image of the Sertão is dry or dead.

These themes of class and wealth divide seem to be a thread throughout your films.

It comes naturally because that’s the kind of conflict that I’m interested in. This is an example, I just thought this out: Some guy in a bar, everybody is getting a beer but he can’t get a beer because the barman is ignoring him. Is this a political situation? I don’t know. But it’s a human situation and it might have happened to everyone. For me it’s a strong scene, everybody has a beer but he keeps being ignored. Why is he being ignored? Is this a Hitchcockian situation? I don’t know. Is it funny? I don’t know. But it’s kind of unnerving.

Depends who you cast.

Yes. [Laughs] Depends how you shoot it and what lens you’re using. And it depends on the actor’s face and his face of disappointment and maybe frustration or anger.

There was a protest when Aquarius played at Cannes. The government appeared to take it very seriously?

The protest politicized Aquarius to levels I never expected. And then all the rightwing maniacs turned against us and all the leftwing people supported us. It became like a war of words, arguments, and social media abuse and social media counterattacks. And then, because we work with public funding, some asshole within the national film agency built this crazy, unprecedented case around the accounting for Neighbouring Sounds. So it was pretty ugly and very unpleasant.

You said at the time that they were trying to “sabotage Brazilian cinema.” Are they succeeding?

They are absolutely sabotaging Brazilian cinema. They have a contempt for the arts and artists. The new guy has declared a cultural war against the left. In my lifetime I’ve never seen anything like this. From when I was a teenager till a few years ago Brazil was always building something, particularly in the area of culture. Now there is a motion to destroy it and demoralize it. But it’s really the wrong year to do that because Bacurau did very well. It was in Cannes. Karim Aïnouz’s film Invisible Life is also doing very well. We have like 15 very good films, one of them here in Marrakech. To make a very long story short, this is a moment that I never thought I would go through, observing something being taken down, being destroyed. The new people appointed to take care of culture, they apparently hate culture. And they also believe that the only beautiful shape of what art should be is opera. Which sounds vaguely fascist.

It really does.

So it’s like a Monty Python skit without the humor–only the absurdity.

Bacurau opens March 6 in the United States via Kino Lorber.