A tale of two Carols: Dickens's festive feast served with a twist

by Arifa AkbarThis year, the tried-and-tested tale at London’s Old Vic is up against subversive surprises at Wilton’s Music Hall, where Scrooge’s sister takes the lead

Charles Dickens knew he had struck gold when he published his “little Christmas book” in 1843. Within a year, A Christmas Carol had spawned nine stage shows, 127 recitals by the author and a pirated version (Dickens, a crusader not only for Christmas cheer but also for copyright, promptly sued).

It hasn’t stopped jolting tears and pricking consciences ever since, with its Christian message for a more compassionate capitalism in the face of child poverty. Except two new London productions are not singing from the same carol sheet about grumpy old men made good.

Jack Thorne’s adaptation is the tried-and-tested one, now in its third run at the Old Vic (★★★☆☆) and also currently on Broadway. A handsome production, it uses every bell and whistle to try and melt the hardest heart, from carol singing to handbell ringing, a stupendous feast in which food is whizzed down to the stage from the gods and a snow-flurry across the auditorium that only mildly whiffs of washing-up liquid.

Matthew Warchus, as director, and Rob Howell, as set and costume designer, ramp up the spectacle with dangling lanterns and lugubrious light and shadows when the three ghosts, all female, appear. The stage is multipronged in shape, reaching into the audience and occasionally inviting participation.

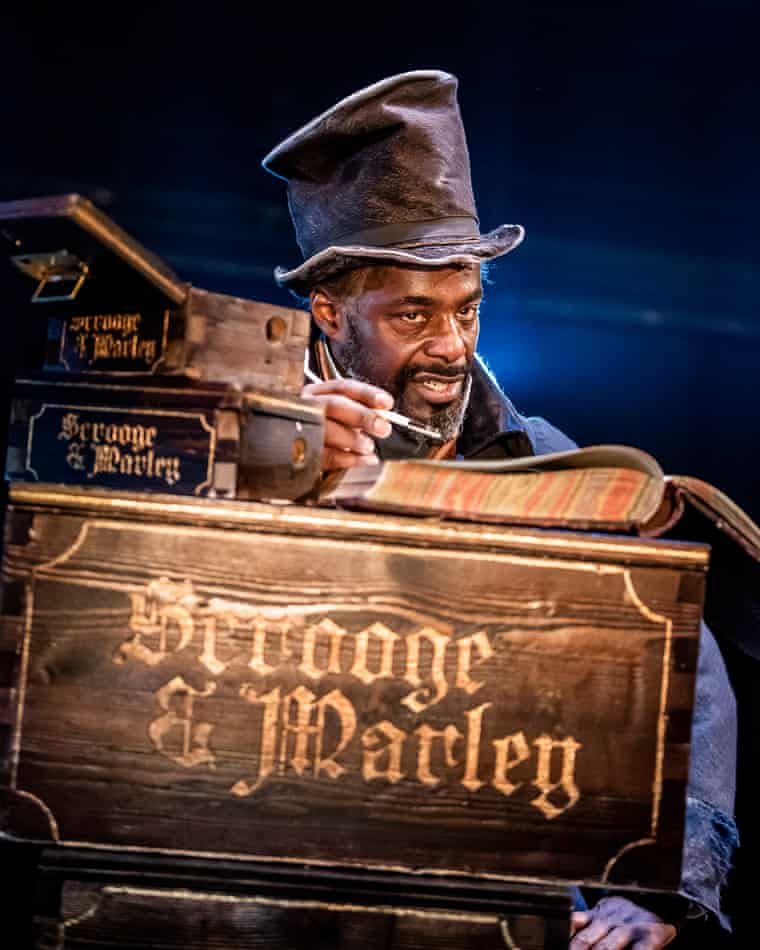

Paterson Joseph’s Scrooge is not an enfeebled old man but an angry physical presence; he twitches his muscles, speaks in stentorian tones and wipes a sea of sweat from his brow. It is a muscular interpretation of the moneylender but does not allow vulnerability in early enough, so Scrooge’s Damascene transformation feels too sudden.

“There is much about comfort in the story,” wrote GK Chesterton of Dickens’s story and Thorne’s iteration offers very traditional comforts, mince pies notwithstanding. It feels polished but twee by the time Tiny Tim (Rayhaan Kufuor-Gray, one of four actors in the role) rings the final handbell and wrings (some of) our hearts.

At Wilton’s Music Hall, Piers Torday’s radical Christmas Carol – A Fairy Tale (★★★★☆) could not be further from tradition; even the turkey is spared from death thanks to a vegan alternative. Scrooge is not Scrooge as we know him either but a “her” – Ebenezer’s sister, Fan, who dies in the novella. Here we find she married Marley and lived with him in miserable marital bondage.

Fan Scrooge is not Dickens’s morally deficient “wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner”, although she has shut up her heart after feeling undermined in Victorian society. Sally Dexter is a bonneted, severe-looking woman with a passing resemblance to Miss Havisham who occasionally speaks with clunky stridency (“I am a woman and I have lived a life men made for me”). More often, she is quick-witted and wry.

“You’ve changed,” she tells Marley when his apparition appears in chains, and then: “I want a divorce.” Guided in part by Friedrich Engels’s The Condition of the Working Class in England (a Christmas present from Bob Cratchit), she invents her own happy ending in which she buys a school for fallen women, turns it into “Fran’s School for Empowered Young Women” and enlists Ann Cratchit to run it.

Everything about this production is delightfully surprising and subversive, even if it feels occasionally scrappy. The satire on gender works on the whole; the ghosts are imaginatively conceived, particularly that of the present – a giant puppet (voiced by Edward Harrison) who has embraced new age philosophies on how to live in “the now”. The ghost of the future is reminiscent of an MR James spectre made of twisted bedsheets (the role is jointly played by Chisara Agor and Ruth Ollman), and projects Fan into the modern day to witness the burdens of the professional woman, multitasking to harrowing degrees.

Jo Lakin’s puppetry is used to charming effect and if Tom Piper’s set design is not as grand as Howell’s, it is still fluid and conjures ghostliness. Torday tells us that Dickens’s own daughter, Katey, felt he never understood women. But “if the courses be departed from, the ends will change”, says Scrooge in Dickens’s story. Maybe this new ending offers both the story, and its 19th-century writer, a welcome 21st-century transformation.

- A Christmas Carol is at the Old Vic, London, until 18 January. Christmas Carol – A Fairy Tale is at Wilton’s Music Hall, London, until 4 January.