Big Bertha: A 25,000 HP Mechanical Worm Designed in Japan for American Drilling

by Alex CarausuIt’s a known fact that engineers, in their constant pursuit for innovations, have learned a good amount from nature itself, as it provides one of the best sources of inspiration.

Before we even existed as a species, nature was already working tirelessly, creating and shaping an effective system in which all elements coexist harmoniously.

Therefore, in a never-ending quest that seeks ingenious and sustainable solutions for our “human challenges”, it seems like emulating nature’s approaches and patterns is the way to go, as its experience in the field is millions of times greater than ours. This term is called Biomimicry, and it represents the process of making use of innovations that exist and work in nature, and applying them to technology development.

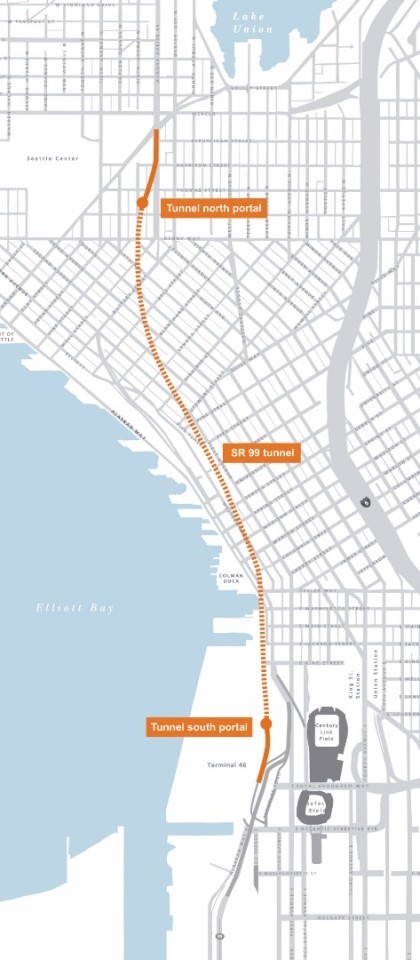

And so it happened when the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) decided to build, well dig to be more precise, an alternative for the Alaskan Way Viaduct which has been damaged and deemed seismically unsafe after an earthquake named Nisqually hit Seattle back in 2001.

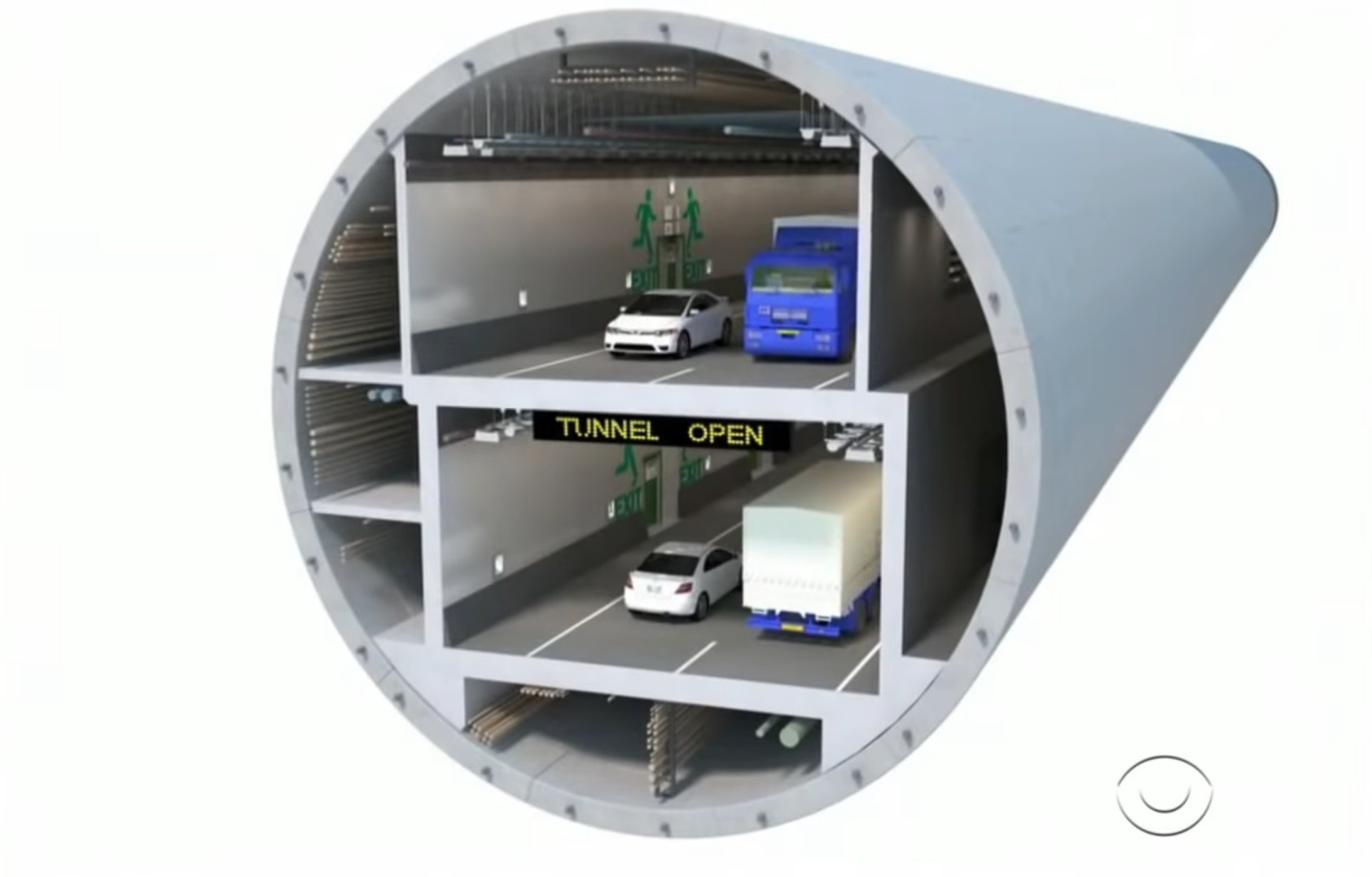

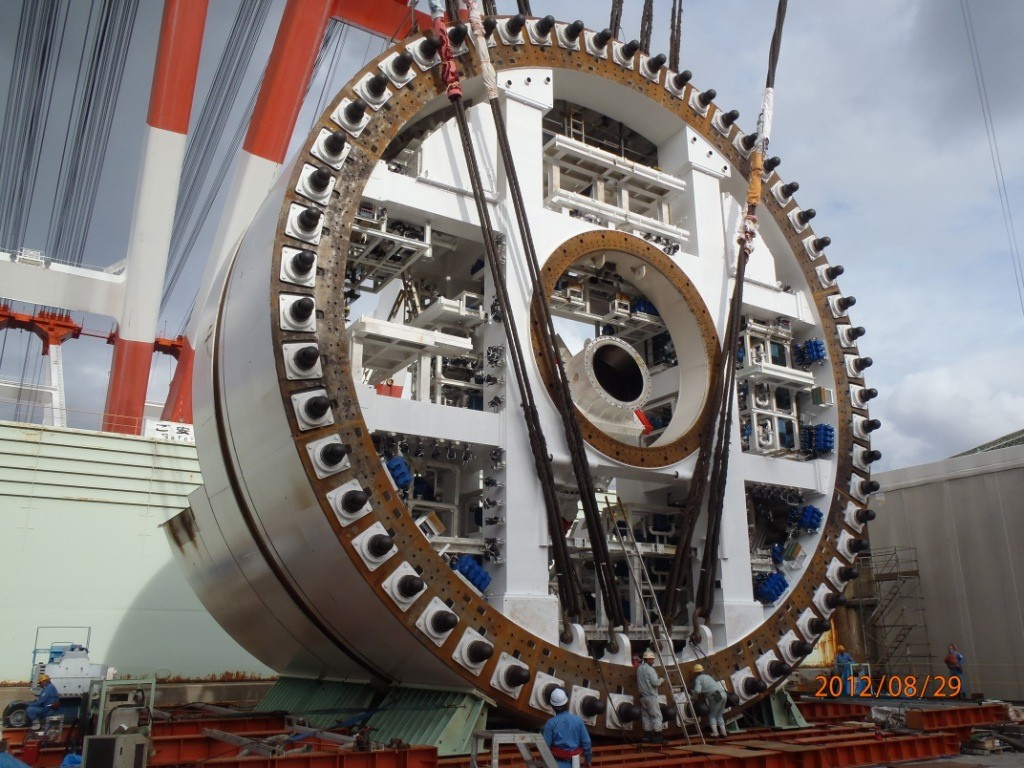

So what do you do when you have to build a 9,270 feet long (2,830 meters) four-lane tunnel at about 200 feet (60 meters) underground, whilst also not damaging the foundations of the city’s skyscrapers and historical buildings? You commission Hitachi Zosen from Japan to build a 57.5 feet (17.5 meters) diameter, 326 feet (99 meters) long worm that weighs over 6,000 tons, and you name it Big Bertha.

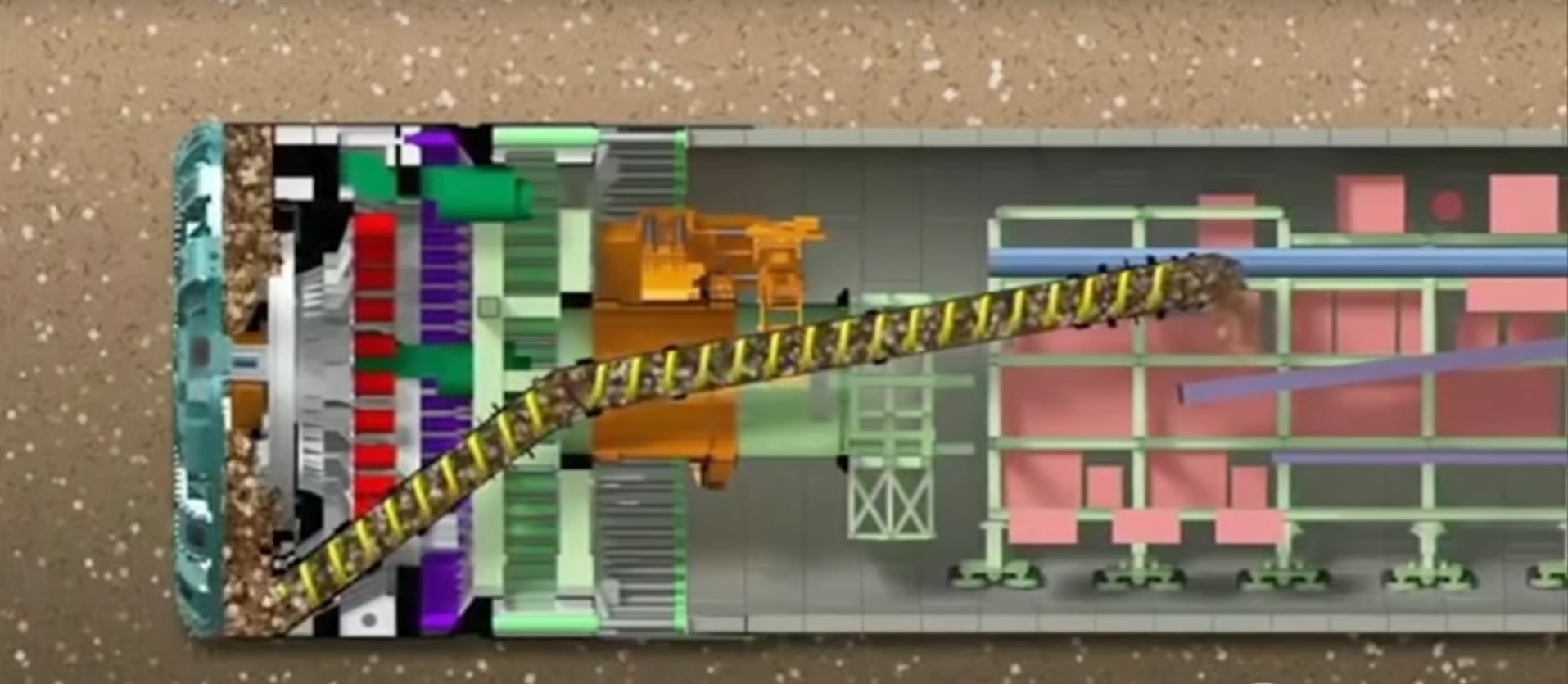

To understand how a modern tunnel boring machine works, imagine a giant earthworm (I know, but bear with me) - the worm eats, the worm moves forward, and the worm spews waste from itself, so in general terms that was the working principle that the machine should respect.

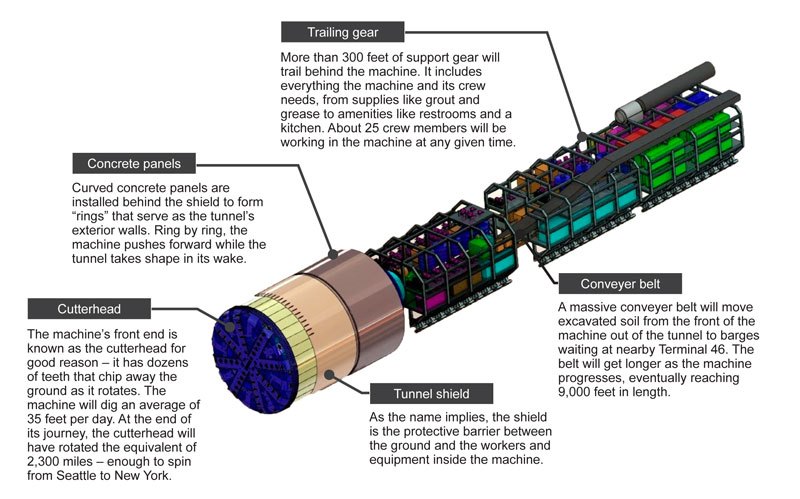

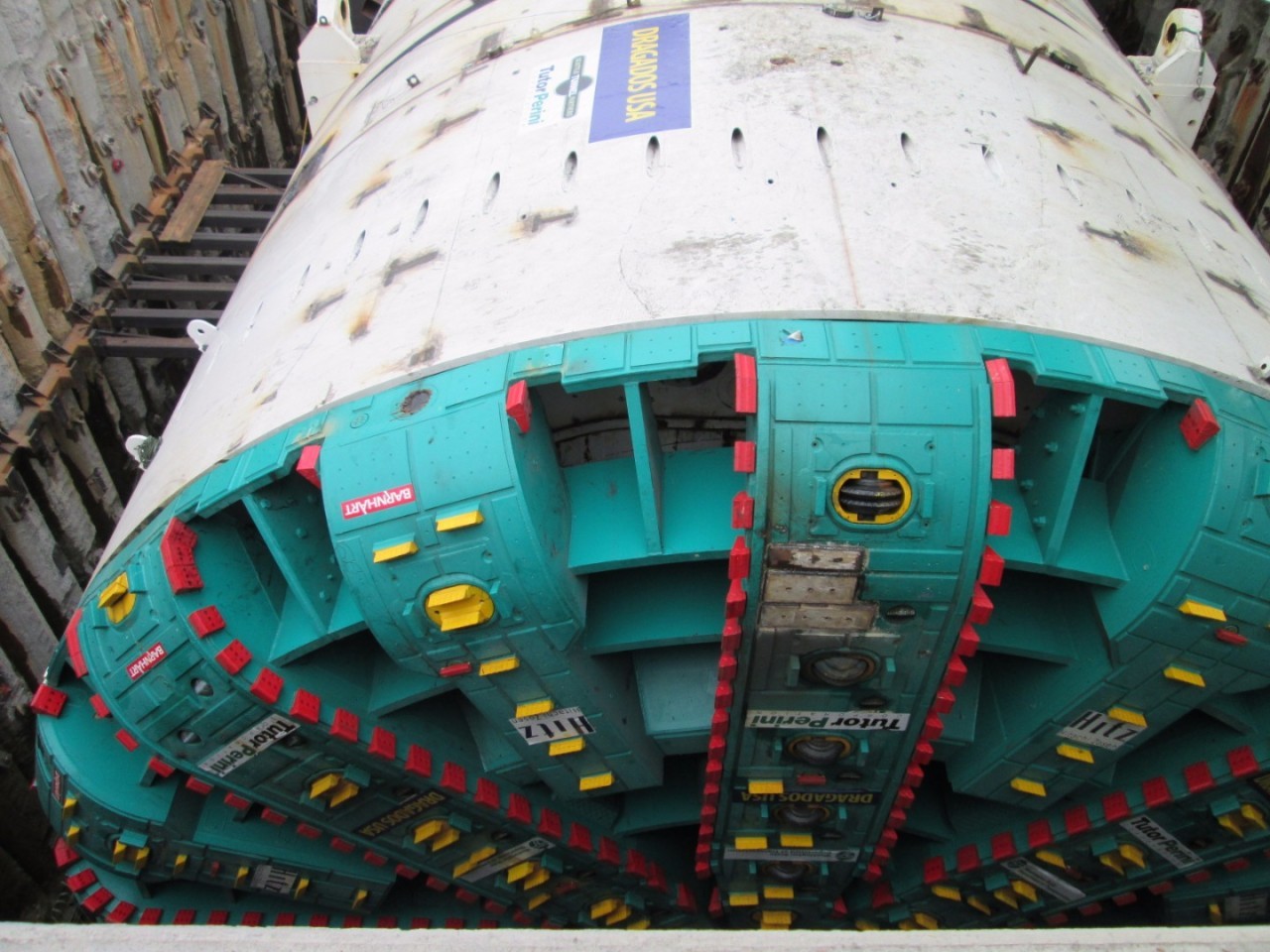

With a head drill composed of 260 fixed and moving cutters, performing a full revolution every minute, and a total weight of around 800 tons, Big Bertha was good for “chewing” around 35 feet (10 meters) of soil every day, thanks to its massive 25,000 horsepower engine. The head is also fitted with special nozzles to mimic a “salivary” system, which turns the waste soil onto a mass with the consistency similar to a paste, easier to move around.

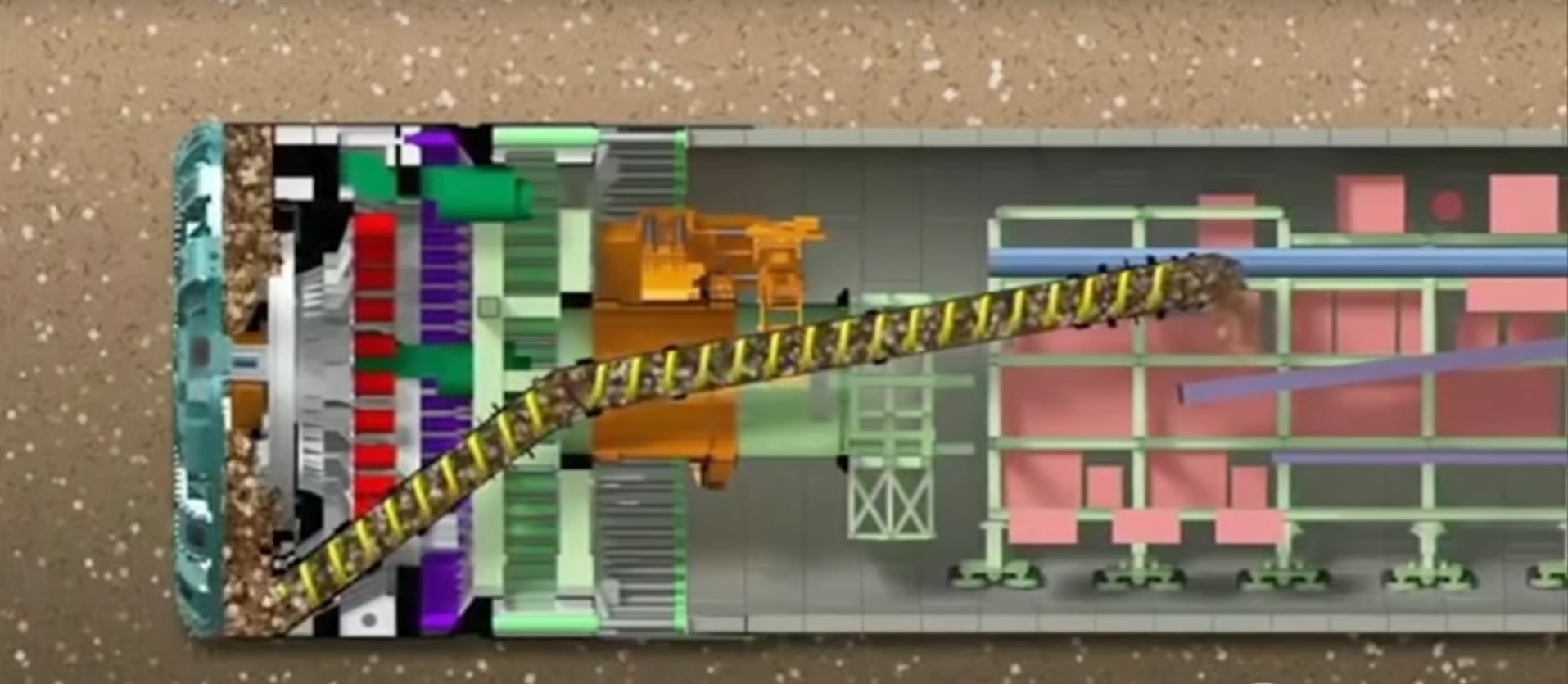

Next comes the “digestion”, where a lot of waste is squeezed onto a huge rubber screw (such as an Archimedean screw) which, thanks to its special design for Big Bertha, can handle chunks of stones up to a meter across. The screw then drives the load to that part of the machine, which can be called "guts" for the lack of any other elegant analogy. Long story short, a conveyor belt removes the waste from the tunnel and unloads it into a barge, moored to the shore of the bay.

The conveyor belt increases in size along with the progress that Bertha makes by drilling, in this case, by the end of its mission it reached around 9,000 feet (2,700 meters). If it wasn’t for this ingenious solution, up to 200 dump trucks would have been released daily to the streets of downtown Seattle in order to transport the waste soil away from the construction site, or they’d have to purchase a couple BelAZ monsters.

If you think that is amazing, the Japanese-built Bertha also installed the concrete panels, building the walls of the tunnel as it goes, and leaving an almost finished project behind. Now that’s impressive.

The whole process should have taken Bertha, on paper at least, around two and a half years, but after just 10% of work disaster struck. Chaos had been created as temperatures spiked, alarm bells started ringing resulting in stopping the giant from digging. After investigating that took a month, WSDOT announced that the cutting blades of the machine encountered a long steel pipe, one of several that were left from a previous drilling project in 2002, following the earthquake in 2001.

Since the machine cannot cut through metal, the pipe damaged several of Berta's cutting blades, requiring a replacement blade before the machine could continue. The weird thing is that WSDOT apparently knew about the location of these steel pipes, and the agency responsible for the project were assured that they were removed. It is currently unclear whether the government or one of its contractors is responsible for the pipes being left behind.

Multiple options have been discussed to solve the problem, resulting in an out of commission period of almost a year. After a long 48 months underground, the besieged behemoth clawed its way into daylight leaving a 1.7-mile long tunnel behind it.

With the job done, Bertha’s mission is now complete and a not so bright future awaits. The front end will be carved up and trucked away, with parts such as wires and motors to be saved and sold back to the manufacturer. A significant part of the steel will go to the local iron foundry for re-melting, after which the metal will be used to build the highway inside the new tunnel.

The tunnel was opened for traffic on February 4, 2019 and it represents one of the marvels of engineering and sustainable solutions. 🏁