A Framework for Regulating Competition on the Internet

by Ben ThompsonA prompt for writing this piece is a conference I will be participating in tomorrow entitled Antitrust in Times of Upheaval — A Global Conversation; you can livestream the conference here.

I opened 2017’s Defining Aggregators by stating:

Aggregation Theory describes how platforms (i.e. aggregators) come to dominate the industries in which they compete in a systematic and predictable way. Aggregation Theory should serve as a guidebook for aspiring platform companies, a warning for industries predicated on controlling distribution, and a primer for regulators addressing the inevitable antitrust concerns that are the endgame of Aggregation Theory.

This Article is explicitly related to that piece: unlike most Stratechery items, this Article is not based on a specific news event that happened recently, but is rather an attempt to collect a number of ideas and thoughts I have expressed in different Articles, Daily Updates, and Podcasts about Aggregators, platforms, and regulation. I will link to several of those Articles throughout.

Platform And Aggregator Structure

The most important place to start is by pointing out the excerpt above makes what I now believe is a critical mistake: it conflates platforms and Aggregators. In fact, I believe platforms and Aggregators are fundamentally different entities, and understanding how and why they are different is the single most important task facing would-be regulators.

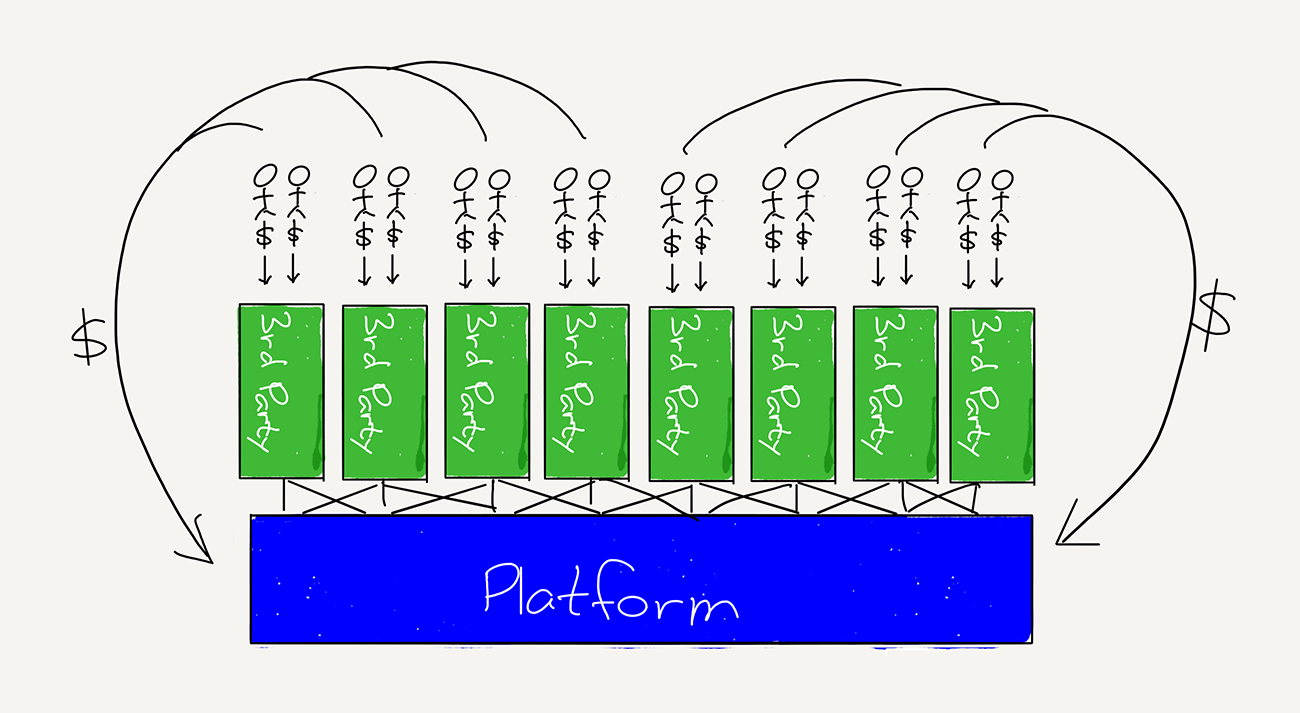

I explored these differences in 2018’s Tech’s Two Philosophies, The Moat Map, and The Bill Gates Line. This is how I illustrated platforms:

The name “platform” is a descriptive one: it is the foundation on which entire ecosystems are built. The most famous example of a platform — one with which regulators are intimately familiar — is Microsoft Windows. Windows provided an operating system for personal computers, a set of APIs for developers, and a user interface for end users, to the benefit of all three groups: developers could write applications that made personal computers useful to end users, thanks to the Windows platform tying everything together.

What is critical to note about Windows, though — and this extends to newer platforms like iOS and Android — is that it was essential for the ecosystem to function. Developers could not write applications for another operating system if they wanted to reach users, and users could not use a different operating system if they wanted to use popular applications.

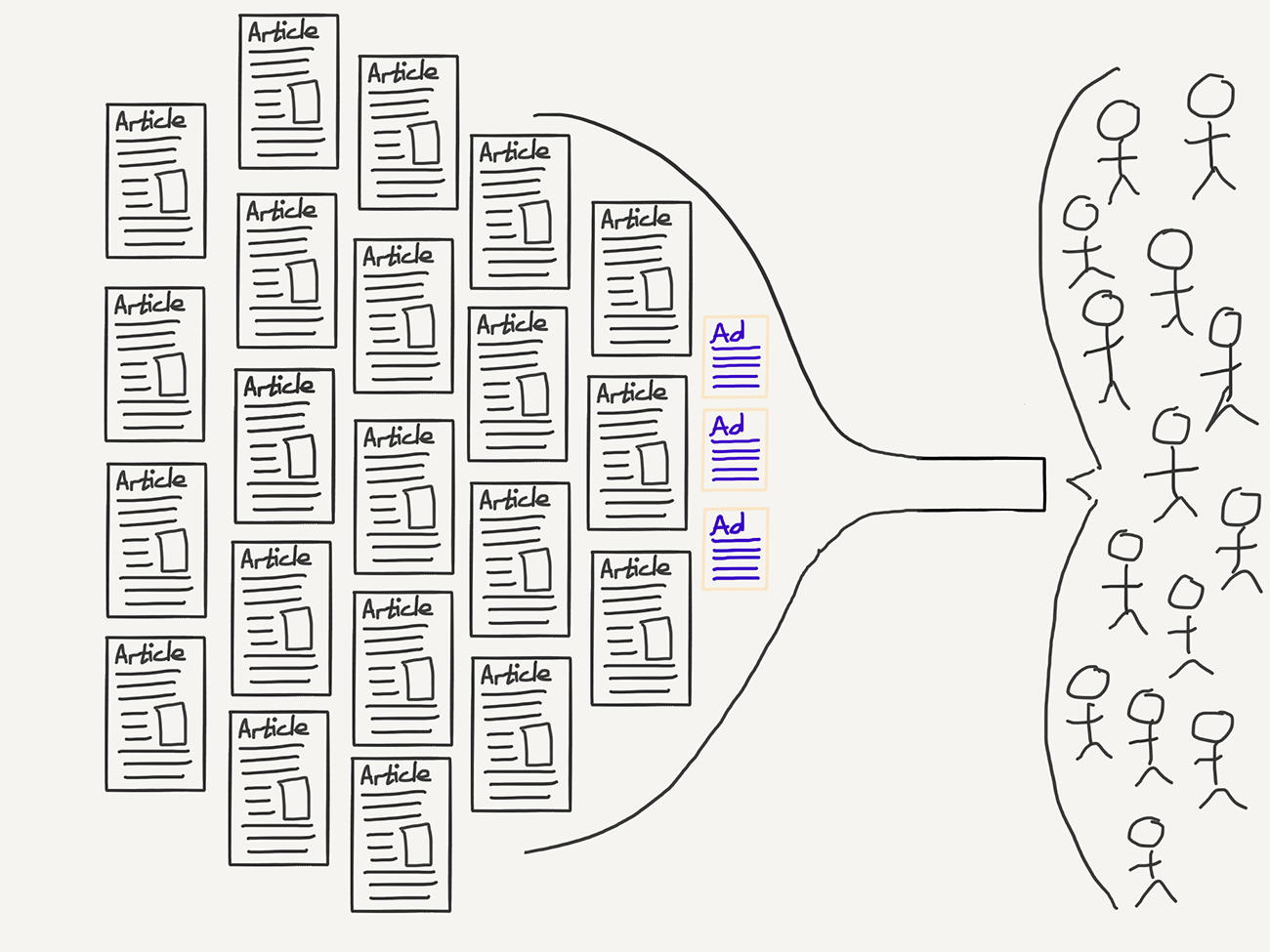

Aggregators are different. This is how I illustrate them:

“Aggregator” is also descriptive: Aggregators collect a critical mass of users and leverage access to those users to extract value from suppliers. The best example of an Aggregator is Google. Google offered a genuine technological breakthrough with Google Search that made the abundance of the Internet accessible to users; as more and more users began their Internet sessions with Google, suppliers — in this case websites — competed to make their results more attractive to and better suited to Google, the better to acquire end users from Google, which made Google that much better and more attractive to end users.

Notably, unlike platforms, Google is not essential for either end users or 3rd party websites. There is no “Google API” that makes 3rd party websites functional, and there are alternative search engines or simply the URL bar for users to go directly to 3rd party websites. That Google is so influential and profitable is, first and foremost, because end users continue to prefer it.1

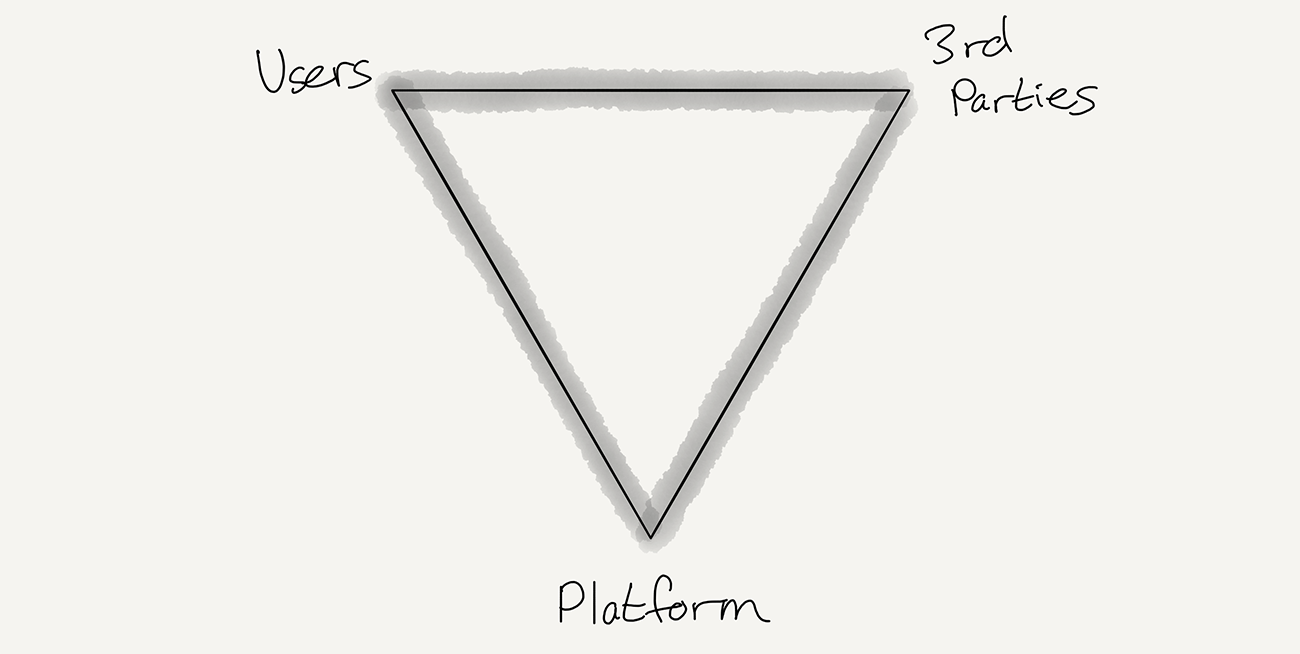

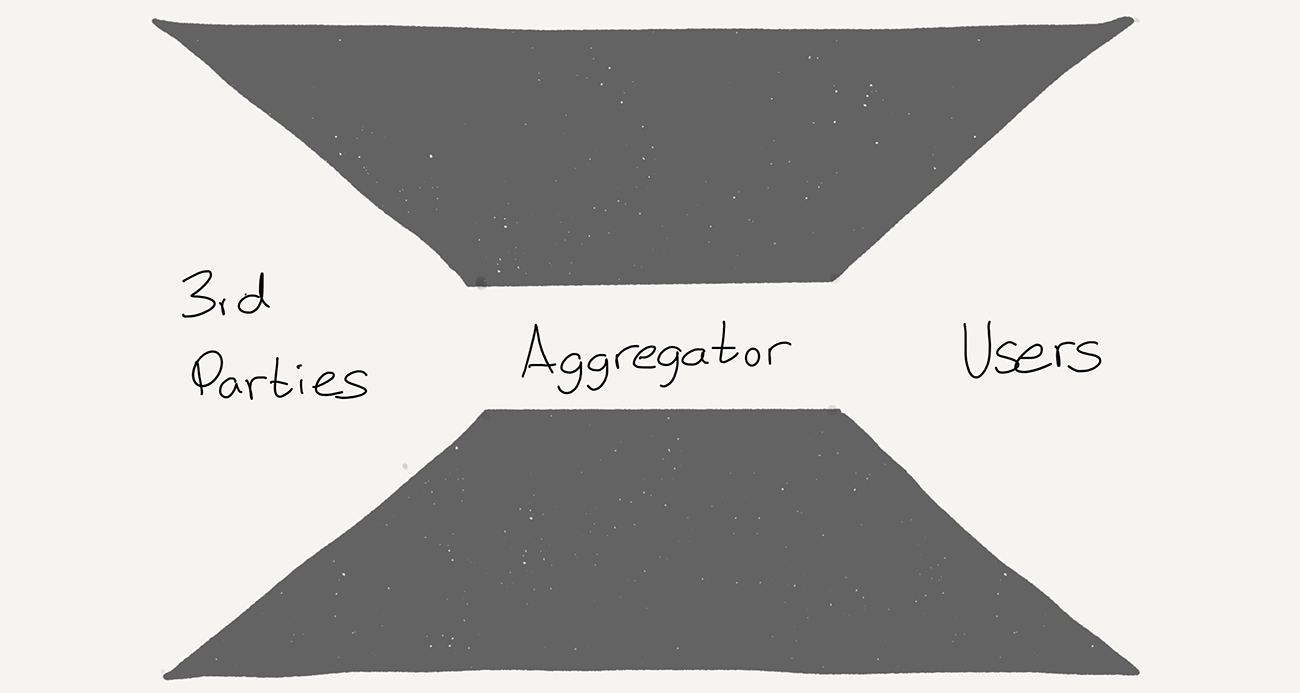

Here is a way to visualize the difference:

Platforms facilitate a relationship between users and 3rd-party developers:

Aggregators intermediate the relationship between users and 3rd-party developers:

To be clear, both roles can be beneficial — platforms make the relationship between users and 3rd-parties possible, and Aggregators helps users find 3rd-parties in the first place — and both roles can also be abused.

Platform and Aggregator Abuse

The potential impacts on competition by Platforms and Aggregators are broadly similar, differing mostly by degree:

Vertical foreclosure: Platforms can make it impossible for 3rd-parties to function on their platform, either through technological means or, in the case of smartphone platforms, by leveraging their gatekeeper role in terms of App Stores.

Aggregators can also ban 3rd-parties — Google can remove a site from search, or Facebook can remove links from the News Feed — but they cannot force that site to simply not exist. Users can still reach those sites via other search engines, links, or by typing in the URL.

Rent-Seeking: Instead of blocking third-parties, platforms can simply extract money; this often works in conjunction with the threat of foreclosure. Apple, for example, does not allow apps that have their own payment processor, or that even link to a website with payment functionality; they are, however, happy to offer their own payment processor, complete with 30% fee to Apple.

Aggregators, meanwhile, make it increasingly difficult to reach end users without paying for advertising; Google and its expansion of vertical search categories like travel is a perfect example. However, Aggregators do not have as strong of a vertical foreclosure stick as do platforms.

Tying/Bundling: Platforms can include additional functionality or applications that have nothing to do with the platform, but rather leverage the platform to gain market share. The most famous example of this is Windows bundling Internet Explorer, the legality of which was never settled in the United States; the Appeals Court remanded the case to the District Court because of concern a per se application would chill innovation (and in this case Microsoft has been proven right: all operating systems come with browsers now).

This is arguably the true Aggregator stick when it comes to rent-seeking: to return to the travel example, online travel agents may not be happy about paying to be a part of Google Search’s travel module and the hit on margins that entails, but it is better than Google launching its own OTA.

Self-Dealing: Platforms can give their own products advantages, often through special APIs that are not available to competitive products. For example, real-time co-authoring of Microsoft Office documents only works in the Office desktop apps if the documents were opened from OneDrive, but not if opened from Dropbox or Box.

For Aggregators, this advantage is more about putting their competitive product in front of users. Google local results, for example, are not even listed in the Google index, yet they are inserted at the top of the search engine results page (SERP).

The question for regulators is when these abuses should lead to action.

Principles of Regulation

That certain companies have advantages or earn sustainable profits is not a sufficient reason for regulators to act; innovation deserves its reward. Moreover, the presence of abuses like those detailed above is also not necessarily a sufficient reason for regulators to act: regulation can have a chilling effect on innovation, it can be ineffective, and it can incur significant opportunity costs on both companies and regulators. Regulators should focus their attention and resources on abuses for which there is no other recourse than regulation.

This is where the distinction between platforms and Aggregators is critical. Platforms are the most powerful economic and innovation engines in technology: they create the possibility for products that never existed previously, and are the foundation for huge amounts of innovation. It is in the interest of society that there be more and larger platforms, not fewer and smaller.

At the same time, the danger of platform abuse is significantly greater, because users and 3rd-party developers have no other alternative. That means that not only are anticompetitive actions unfair to products that already exist, they also foreclose the creation of an untold number of new products. To that end, regulators should simultaneously encourage the formation of new platforms while ensuring those platforms do not abuse their position.

From a practical standpoint, this means that platforms should have significant latitude in mergers and acquisitions, but significant scrutiny in terms of vertical foreclosure, rent-seeking, bundling, and self-dealing.

Apple is the pre-eminent example here: the iPhone specifically and the entire iPhone ecosystem generally has benefitted tremendously not only from Apple’s internally-created innovations but also from acquisitions like P.A. Semi, which led to the creation of Apple’s A-series of chips. However, the combination of Apple’s total control over 3rd-party app installation and rent-seeking on in-app payments has, in my estimation, stunted innovation and opportunity in the app ecosystem.

Aggregators are different. Yes, they provide value to end users and to third-parties, at least for a time, but the incentives are warped from the beginning: 3rd-parties are not actually incentivized to serve users well, but rather to make the Aggregator happy. The implication from a societal perspective is that the economic impact of an Aggregator is much more self-contained than a platform, which means there is correspondingly less of a concern about limiting Aggregator growth.

For the same reason, though, Aggregators are less of a problem. Third parties can — and should! — go around Aggregators to connect to consumers directly; the presence of an Aggregator is just as likely to spur innovation on the part of a third party in an attempt to attract consumers without having to pay an Aggregator for access. Moreover, there is a Sisyphean aspect to regulating power predicated on consumer choice: look no further than the European Union, where regulators are frustrated that remedies for the Google shopping case aren’t working, even though those same regulators were happy with the remedies in theory; the problem was trying to regulate consumer choice in the first place.

It follows, then, that regulatory priorities should be the opposite of platforms: given that Aggregator power comes from controlling demand, regulators should look at the acquisition of other potential Aggregators with extreme skepticism. At the same time, whatever an Aggregator chooses to do on its own site or app is less important, because users and third parties can always go elsewhere, and if they don’t, that is because they are satisfied.

Here Facebook is a useful example: the company’s competitive position would be considerably shakier — and the consumer ad-supported ecosystem considerably healthier — if it had not acquired Instagram and WhatsApp, two other consumer-facing apps. At the same time, Facebook’s specific policies around what does or does not appear on its apps, or how it organizes its feed, has no reason to be a regulatory concern; I would argue the same thing when it comes to Google’s search results.

There is one additional area where regulators should focus: advertising. Advertising is a core component of Super-Aggregators like Facebook and Google because the incentives are perfectly aligned: Facebook and Google want to serve everyone, which means they want to be free, while advertisers want to have access to everyone, which means coalescing around the largest Aggregators.

First, this results in a type of market failure when it comes to problematic content, as I detailed in A Framework for Regulating Content on the Internet. Second, the sheer scale of the core Aggregator gives a massive scale advantage that can be applied elsewhere; Google in particular is much more of an inescapable platform when it comes to advertising on third party sites; this is where regulatory scrutiny should be focused.

There is one final component to this analysis: if platforms and Aggregators are to be treated differently, regulators need a more flexible way of considering when is the correct time to step in.

Consider the three regulatory issues that I implicitly suggested deserve more attention in this piece: Apple’s App Store policies, Facebook’s acquisitions, and Google’s third-party advertising offerings. None of them fit under a popular conception of a monopoly: Apple sells a minority of smart phones, Facebook acquired Instagram when it had only 30 million users, and the advertising market is both not consumer-facing and has infinite supply.

That doesn’t mean harms don’t exist, though: the apps and services that aren’t created, the advertising-based consumer services that are under-monetized (Snapchat and Twitter) or that aren’t even being funded, and the multitude of websites that can’t realistically even try innovations that entail going around Google.

That, though, is why I am writing this piece. Cases like the European Commission Google Shopping case are excellent examples of how a lack of clear standards lead to sub-optimal outcomes that don’t actually change anything; at the same time, the European Commission’s investigation of Apple’s App Store will surely benefit from increased flexibility in defining relative markets.

Ideally, there would be stricter adherence to better rules, instead of finger-crossing that Brussels gets it right. That, though, likely requires new laws. Indeed, while that seems like a slog, it should, in my estimation, be the focus of those interested in a future where we direct tech’s innovation towards making a larger pie for everyone, as opposed to cutting off slices because it makes us feel better, even if only temporarily.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

Google also, to be clear, pays significant amounts of money to ensure it is the default on iOS, and basically built Android to ensure it is the default everywhere else. The European Commission correctly found Google’s contractual moves to secure its position on Android illegal [↩]