Comics and graphic novels

Aivali: A Story of Greeks and Turks in 1922 by Soloup review – a moving graphic novel

The traumas of the Turks and Greeks forced to flee their homes a century ago are drawn with moving simplicity and speak clearly to today’s refugee crisis

by Thanos KyratzisThe distance between the ports of Mytilene, on the Greek island Lesbos, and Ayvalık, a Turkish city known as Aivali in Greek, is 47.5km by sea. Between 1922 and 2019, millions of people have crossed the unpredictable waters, many of them fleeing wars around the world.

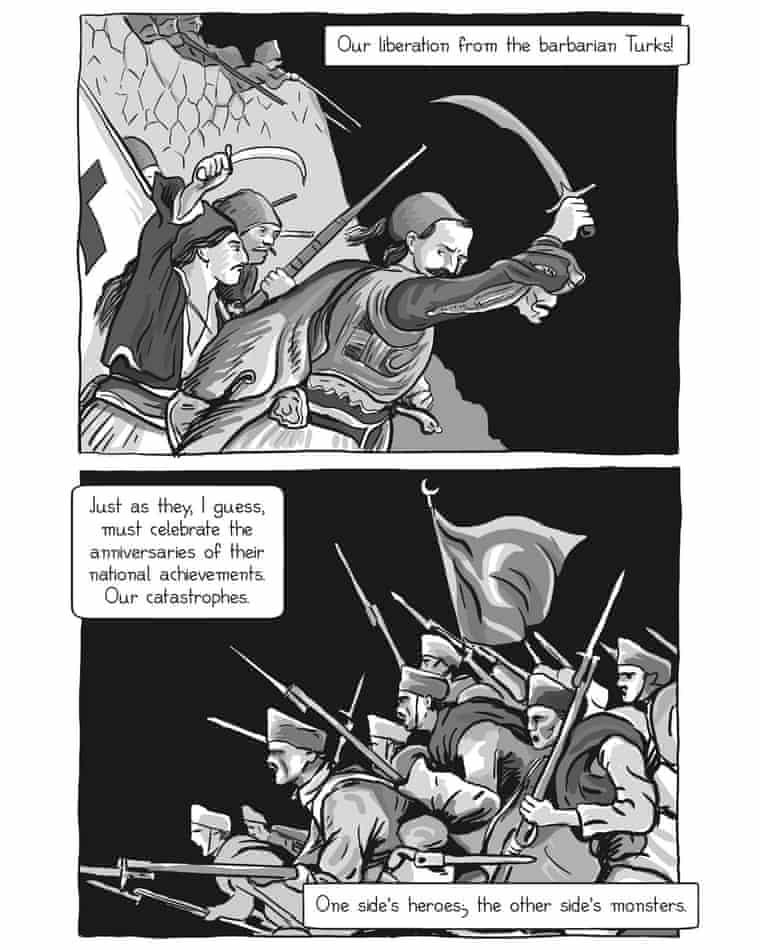

Aivali: A Story of Greeks and Turks in 1922, a graphic novel published in Greek in 2014 and recently translated into English by Tom Papademetriou, is the story of the 1.6 million refugees who made the journey that year alone, when the Greek and Turkish governments agreed to a massive population exchange at the end of the Greco-Turkish war. The Greek Orthodox Christians of Asia Minor and other Turkish regions were made to relocate to Greece, while Muslim Greek citizens were forced into Turkey. Both sides suffered, and this is the strongest message in this soul-stirring account, which acknowledges all sides of the tragedy.

Aivali starts and ends with the story of Antonis, named after the graphic novel’s creator (Soloup is his pen name), who took the ferry from Mytilene to Aivali in 2014 to better understand what his family left behind when they fled Turkey in 1922. But the bulk of the story is set in the past, built on real accounts of three refugees: Fotis Kontoglou and Elias Venezis, who were moved from Turkey to Greece, and Ahmet Yorulmaz, a Muslim who was sent to Turkey. Their words are visceral, ringing with the pain and stigma of forced displacement.

Soloup’s black and white pen lines are simple and fragile, but the story behind them is anything but. A renowned political cartoonist in the Greek press, he adapts his cartoonish style to harmonise with the story’s solemn gravity. Even when he deviates from his usual style to adopt deeper, more detailed lines that are closer to a woodcarving than a comic illustration – in homage to Fotis, a notable woodcarver in his time – it never disrupts the flow of the narration.

Current events loom over the book and Soloup makes the connection to Greece’s most recent refugee crisis. When he tells the real story of a Turkish soldier saving a Greek girl from being killed by his comrade in 1922, it is easy to see the same spirit in people today, as with Maritsa Mavrapidi, a Greek grandmother in Mytilene and former 1922 refugee herself who famously tended to Syrian refugee children when they arrived by boat in 2016. The Greeks and Turks endured being traded like chips in a card game; nearly a century later, Aivali shows how this trauma has been carried through generations in Greece and Turkey, as well as highlighting the suffering of displaced people fleeing violence around the world today – including the 50,000 refugees currently scattered over the Greek mainland and islands.

Soloup’s art and words offer a glimpse of the strength of the human spirit, showing how people on both sides of those waters were persecuted, yet also found the power to forgive and help each other. There is no hollow empathy found here. Soloup demonstrates how problematic it is when human beings are treated like statistics. Aivali doesn’t shy away from showing the complexity of human lives – on either side – and the ongoing struggle for some, still searching for a place to call home.

• Aivali: A Story of Greeks and Turks in 1922 by Soloup, translated by Tom Papademetriou, is published by Somerset Hall Press.