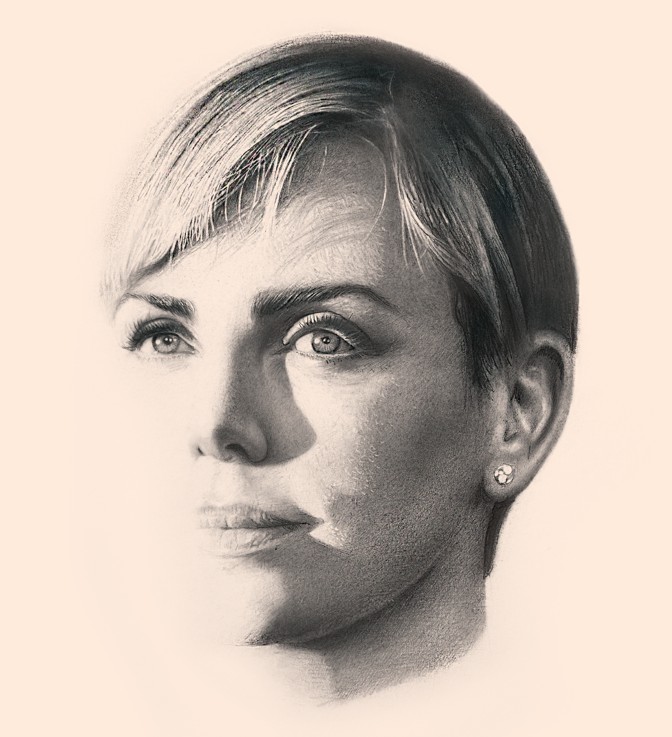

Charlize Theron Knows a Monster When She Sees One

by Abby Aguirre- Link Copied

Charlize Theron received the script for Bombshell, the new drama about the women who exposed sexual harassment at Fox News and brought down Roger Ailes, in the summer of 2017. Two months later, the first Harvey Weinstein story broke. In certain Hollywood circles, people had been aware that a Weinstein investigation might finally make it into print, but nobody could have foreseen the magnitude of the fallout or the movement it would ignite. “There was something in the air,” Theron recalled one morning in October, tucked into a corner table at a Hollywood restaurant. “I didn’t have an inkling of how big it was going to be or how long it was going to last.”

Among the things that ultimately drew Theron to the Ailes story—what led her to sign on to star and produce Bombshell—were the women at the center of it: the formidable blond protagonists of Fox News. There was Gretchen Carlson (played by Nicole Kidman), the former Miss America and longtime anchor who filed the initial lawsuit against Ailes, accusing the Fox News chairman of making sexual advances and then retaliating against her after she rebuffed them. There was Megyn Kelly (Theron), the network’s biggest star, who came forward with allegations against Ailes in the weeks that followed. And there was a young female producer (a composite character played by Margot Robbie) who seeks out Ailes in hopes of landing an on-air position, only to be cowed into showing him her underwear during a one-on-one meeting, among other indignities.

“Nothing is black-and-white in this,” Theron said of the film, which was directed by Jay Roach and written by Charles Randolph. She noted that Kelly had moved past her uncomfortable encounters with Ailes and managed to have a professional relationship with him for a decade. What’s more, Theron pointed out, Kelly knew Carlson’s allegations were likely true, because Ailes had harassed her, too.

The gray area includes Ailes’s secretary, played by Holland Taylor, who ferries young women in and out of Ailes’s office and presumably notices his habit of locking the door behind him. Theron likened this gatekeeper to Ghislaine Maxwell, the longtime associate of Jeffrey Epstein who accusers say served as a kind of fixer, recruiting girls and women into Epstein’s alleged sex-trafficking web. “She knows exactly what’s happening,” Theron says of the secretary character. “I’ve never seen us brave enough to look at women fully, whether we’re complicit or we’re sitting in the room and having to placate.”

Read: The myth of the ‘underage woman’

That may be true, but no other leading lady seems as intent as Theron is on jolting us into looking at women fully. Now 44, Theron was still in her 20s when she moved away from sweetheart roles to play the prostitute turned serial killer Aileen Wuornos in Monster. (This after reportedly firing a manager for sending her too many scripts in the Showgirls vein.) She won an Academy Award for Best Actress in 2004 for the performance and has studiously avoided Hollywood typecasting ever since.

Theron’s characters are rarely “likable,” at least in the conventional sense. In Young Adult, written by Diablo Cody and directed by Jason Reitman, she plays a spoiled author of young-adult novels who returns to her Minnesota hometown in an effort to lure her high-school boyfriend out of his marriage. In Tully, another Cody-Reitman project, she portrays an exhausted mother of three with postpartum depression. Even Theron’s action heroines tend to be more than a little damaged—as is literally true of Furiosa, the one-armed warrior in Mad Max: Fury Road.

If there are no easy martyrs in the wasteland beyond Thunderdome, there are none at Fox News, either. Fans of The Kelly File will recall that the anchor once spent a segment arguing that Santa Claus and Jesus were white. (Her NBC show, Megyn Kelly Today, was canceled in 2018 after she defended blackface as a Halloween costume.) “They have all said things that I find highly offensive,” Theron told me. “But when we fight for things—if we believe in equal rights, that women should have safe work environments—we cannot cherry-pick who that belongs to.”

Nor does Bombshell lend itself to easy tropes of sisterly feminism. Carlson and Kelly were not close. Indeed, the film shows Carlson’s shock when Kelly came out against Ailes. “It’s pretty well known that they are not crazy about each other,” Theron said. “That is good territory to cover. Not in the sense that women want to fuck each other over. It’s that we’re just as complex as men, and not all of us get along, and that’s okay. We can work in a space and be really good at our jobs and not have everybody be best friends and have slumber parties. Let’s kill that, okay? We’re all individuals.”

To hear her tell it, the salient thing to know about Theron’s childhood is that she grew up in apartheid-era South Africa, in a small town outside of Johannesburg called Benoni. Theron says it took her decades to come to terms with the implications of racial segregation. “It’s by pure luck that I was born in [South Africa] with white skin,” she told me. “I was a minority. And I was benefiting from the suffering of other people. I know that I had an awareness, because my mom would talk about it. But I didn’t fully understand what that meant until I was living [in the United States] and I could see it with some distance.”

Journalists tend to highlight another detail. When Theron was 15, her father, a verbally abusive alcoholic, came home after a night of drinking and threatened Theron and her mother with a shotgun. As he fired shots, Theron’s mother reached for her own handgun and shot back, killing Theron’s father and wounding his brother. (Officials eventually determined that Theron’s mother, Gerda Jacoba Aletta Maritz, had acted in self-defense.) Theron has never appeared eager to discuss the episode, so I was surprised when she mentioned it in passing. “People always tried to assume that they knew where my pain was coming from, and I was always very defensive about it, because I was like, That was one night of my life. Pain comes from things that you experience day after day after day.”

By the time her mother’s three-year legal ordeal had ended, South Africa was on the brink of civil war. Theron was in New York City, where she took classes at the Joffrey Ballet and pursued an unlikely modeling career. (Unlikely only to Theron, it seems, who spent most of her first decade without teeth—a consequence of antibiotics used to treat a case of jaundice.) Knee injuries were derailing her long-term prospects in ballet, so Theron had to figure out another career path or return to South Africa. Maritz suggested that she try acting and bought her a one-way ticket to Los Angeles.

Theron arrived in Hollywood in 1994, an 18-year-old still working on her English (her first language is Afrikaans). She lived hand to mouth going out on auditions. On her first one, Theron recalled, a director put his hand on her knee, requiring that she make a quick escape. I asked her if she drew on that episode for Bombshell. “That experience is embedded in my body,” she told me. “It’s not an isolated experience. It’s an experience that I share with a lot of women.”

One reason Theron was able to chart an unorthodox course through Hollywood is that she eventually began developing her own projects. Here again, Monster marked a turning point. Though the movie was a box-office success, it was initially considered a risk. Theron had to sign on as a producer to make sure it got made, and to protect the integrity of the story. Through the production company she founded, Denver & Delilah, Theron went on to produce many of the films in which she has appeared, plus a host of other projects.

Theron’s company is now located at Universal Studios. She lives “somewhere in Hollywood,” in the first house she ever bought, 21 years ago. Although she was engaged, briefly, to Sean Penn, she has never married. She is raising two young adopted children with Maritz, who she refers to as her “co-parent.” Both of Theron’s children are African American. “I’m at that place now with my oldest where we talk about the civil-rights movement and stuff like that,” Theron told me. The similarities between South Africa and the United States can be demoralizing, she added. “I’m telling her these stories. And then I get in bed and I turn the television on and I’m like, What the fuck has changed?”

We tend to think of the seismic #MeToo reckoning as beginning in Hollywood, but Bombshell reminds audiences that Fox News had already undergone a similar upheaval. Though some may regard Hollywood and Fox News as political opposites, the film makes the case that women in these two settings have more in common than they think.

It is impossible to watch Bombshell without recognizing the similarities between Harvey Weinstein and Roger Ailes. “Both are incredibly charming,” Theron said. “They can be paternal. They can be great advisers, people who fully invest. They want you to do great. But they want all of those things on their terms. They were both at the epicenter of incredible corporations where women wanted to work.”

The dynamics that brought each man down are similar as well. After Carlson filed her lawsuit, the whisper network at Fox News reached a critical mass of voices, which Bombshell dramatizes with a cinematic montage of women naming names. “Very similar to the Weinstein situation,” Theron said. “Once there were two or three voices, it was like … a wildfire.”

There’s another parallel. If Donald Trump’s rise was an indirect catalyst of the #MeToo movement, it was a far more direct one in the evolution of Megyn Kelly. The events may feel like a distant memory now, but in the year leading up to Carlson filing her lawsuit, Kelly’s life was thrown into chaos after she challenged Trump during the first Republican presidential-primary debate in 2015. The next day, Trump remarked that Kelly had “blood coming out of her eyes, blood coming out of her wherever.”

Trump continued to attack Kelly for eight months. According to Kelly’s 2016 memoir, Settle for More, Ailes made private attempts to assuage Trump but did not hit back publicly. In early 2016, worn down by Trump’s campaign against her and by heightened security issues, Kelly decided to put a stop to Trump’s behavior with a televised face-to-face interview in Trump Tower. “I think at that moment, that was crushing for her,” Theron said. “Like a good little soldier, she went back. She groveled and had that horrible interview with him that’s cringeworthy to watch, where she’s just giggling. When you watch that entire interview, I can see a woman who is doing something that she doesn’t want to do.”

Bombshell ends with the Ailes story, but Kelly’s saga isn’t over. The journalist Ronan Farrow’s book Catch and Kill, published in October, contains allegations that Farrow’s former employer, NBC News, shut down his investigation of Harvey Weinstein after Weinstein made it known to the network that he was aware of harassment allegations against one of its biggest stars, Matt Lauer. (NBC has denied this.) Kelly had been critical of NBC’s response to the Weinstein story—she had called, on air, for the network to have an external investigation conducted into its handling of Farrow’s reporting, as Fox News had done with Ailes. The allegations in Farrow’s book have fueled speculation that Kelly’s firing may have had more to do with her Lauer coverage than her blackface comment.

From March 2017: Can Megyn Kelly escape her past?

The day after Farrow’s book was released, Kelly went on Fox News’s Tucker Carlson Tonight and demanded that NBC release any potential Lauer accusers from their nondisclosure agreements. About a week later, NBC did release past employees from any such confidentiality agreements. When I met with Theron, news had recently broken that former Fox News staffers, including Carlson, were demanding to be released from their own NDAs. “There is strength in numbers,” Theron told me. “I saw a quote from [former Fox News host Juliet Huddy] yesterday who just went, I’ve lost everything. What are you going to come after? Of course I’m going to break my NDA. I have nothing. Most of the women who’ve been fired—they’ve never worked in the same industry again. They can’t get a fucking job … It takes [Huddy’s] kind of reckless behavior for something to really change.”

This may be the grimmest parallel, of course. It’s impossible to know just how many women have had their careers derailed by men like Ailes and Weinstein. Theron hopes Bombshell will remind audiences that sexual harassment and assault is “a nonpartisan issue.” I asked Theron whether she thought that anything had changed in Hollywood. Not quickly enough, she replied. “I think for the first time, though, my industry is embarrassed … In that sense, I think, if we have to shame our way through this, then that’s what we have to do.”

This article appears in the January/February 2020 print edition with the headline “The Patron Saint of Complicated Women.”