Crossword blog

Crossword blog: the New Yorker's cryptic puzzles

The New Yorker has retrieved from its archives some puzzles from its cryptic series. What do you think of them?

by Alan ConnorLast year, we were delighted to see that the New Yorker had begun a crossword series, which has since gone twice-weekly. I feigned annoyance that the puzzles weren’t cryptic; they are, in fact a challenging and literate take on the American puzzle style, which often misleads in a way that’s not a million miles from our own crosswords.

The New Yorker did have a cryptic – in the 1990s. Last month, the magazine created the post of puzzles-and-games editor. Liz Maynes-Aminzade is the inaugural honcho and, she tells me, was persuaded by her colleague Nick Henriquez to try solving some of the cryptics in the archive. “I had to really sweat through the first five or so,” she says, “but then something clicked. Now, of course, I love them.”

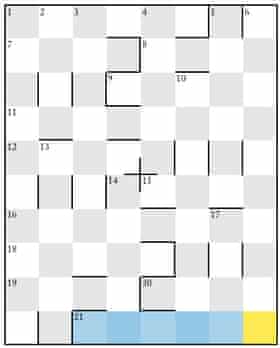

A batch of the old puzzles has reappeared as a kind of Thanksgiving gift, with more to follow weekly. They’re very moreish, partly because they use 10-by-8 grids (in “portrait” orientation); I presumed that this was solely to give newcomers a gentler solving experience, but there’s more to it. Says Maynes-Aminzade:

Hendrik Hertzberg, the senior editor who originally launched the cryptic (with the blessing of Tina Brown, the British editor of the New Yorker at the time), devised this grid design so the puzzle could fit into a single column of the magazine.

Of course the visuals were part of the decision. And in terms of construction, the clues are closer to the Guardian’s quiptic (“for beginners and those in a hurry”) than, say, an Enigmatist workout. I wondered what would be the American equivalents of all those British abbreviations from cricket and the armed forces that make UK cryptics that little bit tricker for non-native solvers. Letters denoting things from private healthcare, sports leagues and the way they name their radio stations, perhaps?

But the hurdle isn’t there. “When our puzzles use abbreviations and initialisms,” says Maynes-Aminzade, “they tend to be common ones: periodic table elements, cardinal directions, etc. In other words, our puzzle is easier than yours!”

“Maybe the closest analog,” she adds, “would be names of American actors – I’ve seen multiple puzzles that play on SLY for Sylvester Stallone, for instance. But I imagine even these references to the Italian Stallion will be legible to British solvers.”

They are, and it’s worth noting here that it’s a shame that I come across the fine Irish actor Stephen RAE more often in American puzzles than I do in the film pages of British papers. And in the New Yorker’s cryptics, there are more British bits and pieces – ETON collars, say – than I had expected to find. Does the American cryptic community overlap with the anglophone gang?

I only have anecdotal evidence, but I highly suspect it does. The New Yorker once published a cryptic that had ADAM BEDE in the grid – clued ‘Plot in a lady’s novel’ – if that tells you anything. (Mr Bede is not exactly a household name over here, it pains me to say.)

Yes, we know the type. Some of them probably even read the Guardian. Two of the paper’s setters, Anna Shechtman and Erik Agard, have made a video guide to cryptic wordplay. Depending how the old puzzles go down, we may be seeing some new cryptics from the likes of that pair. I hope we do.