This was supposed to be the climate crisis election. So what happened?

by Stephen BuranyiThe public want action, but with the Tories obsessed with Brexit, the issue hasn’t gained traction in the media

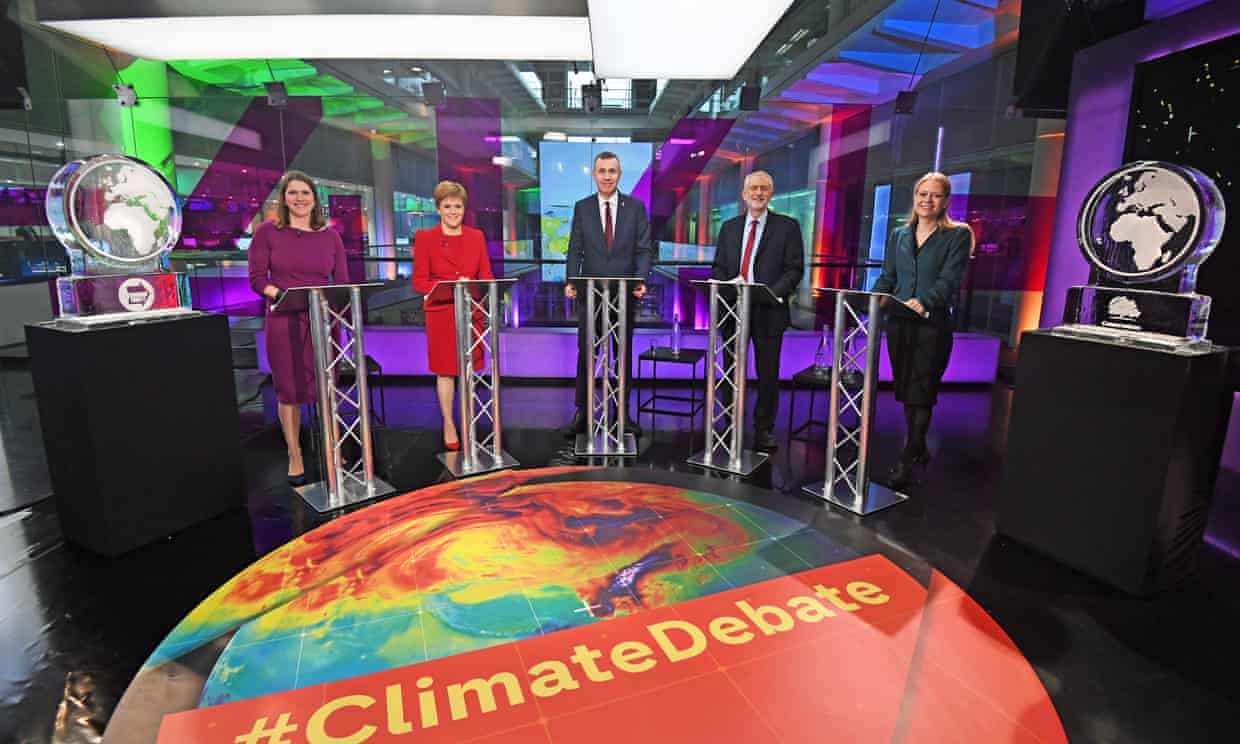

The moment I began to lose hope that this really would be “the climate election” came the day after Channel 4 hosted its climate debate. For the first time in British history, party leaders had gathered to discuss how to tackle the climate crisis. Yet the papers and morning TV and radio shows didn’t seem particularly interested in the discussion: they spent more time talking about Michael Gove and Stanley Johnson’s Borat-esque attempt to storm the doors with a camera crew.

It’s useless to waste energy blaming Gove, the chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, for this. There is a term used in basketball to explain the behaviour of an incorrigible gunner who hoists a shot at every opportunity: shooters shoot. It’s just their nature. Gove goves, meaning if you trot him out, he does personally and professionally debasing things in front of television cameras to lock down their attention.

Besides, this isn’t just about the media’s weakness for the stuntmen of British politics – Boris Johnson, Gove and Nigel Farage chief among them. It’s part of a larger failure to seriously report on or analyse climate policy during this election campaign. It is, admittedly, difficult to cover the climate crisis: no journalist or organisation has yet nailed the perfect balance of scientific perspective and personal connection, of apocalyptic warning and hope.

But the situation in this election seems particularly straightforward. There is a public galvanised by a year of popular protest, who consistently say that they care deeply about the climate crisis and want it addressed – that it will influence their vote. There are also multiple political parties that have committed to bold, transformative climate policies, but with markedly different approaches. If only there were some institution in public life to bridge that gap, to mediate that conversation.

So far, it hasn’t happened. There has been a steady drip-feed of straight reporting of the parties’ policies, and the Channel 4 climate debate was a big step forward. But across the media landscape there is remarkable resistance to having a serious discussion about climate politics and how far they’ve come. The incredible scale of the proposals makes this especially baffling. Just on the plain numbers, Labour has committed to £250bn in public spending to fight the climate crisis, the Liberal Democrats to £100bn, and the Greens £1tn. To give a sense of scale, the Iraq war cost the UK £9.6bn, the war in Afghanistan £20.6bn and bank bailouts between 2008 and 2011 cost the UK taxpayer £124bn. I believe all of those things were widely talked about.

In the policies themselves, there are commitments to epochal, systemic changes that would transform the landscape of this country and the daily lives of its inhabitants. Labour’s green new deal would shift nearly a million workers into new industries and slate nearly every home in the UK for refurbishment. The Lib Dems have broached the possibility of a flight tax to reduce aviation emissions, something no other country has yet instituted. Yet despite the novelty and scale of the proposals, the British media has shown frustratingly little curiosity in analysing or unpacking them. This isn’t really so surprising. The media has come in for plenty of criticism in this election cycle, and much of that criticism applies equally to its climate reporting. There is a deep conservatism in the British press that tends towards dismissing or resisting potential changes to the current order – and in most cases, avoids discussing them at all. It is as if it lacks the theory or the language to do so.

There are established narratives about the issues, about politicians and about the electorate that can’t be dislodged. The recent tectonic shift in public opinion and political will on climate over the past year can join the polarisation of the electorate, the “Faragisation” of the Conservative party, and even the longrunning and obvious push to privatise the NHS, as issues the media seems incapable of grappling with.

And then there is the fact that climate reporting has always proceeded on a separate track, in a silo apart from mainstream concerns. Facts are reported, but in discussion and analysis, there is a pervasive sense that things aren’t about to change – despite all evidence to the contrary. We are told by scientists, activists, and now by the majority of our politicians that we face perhaps the greatest crisis in human history, and that immense upheaval is coming. For all the impact this has made on the coverage of this campaign, you’d think it was happening on another planet.

When this contest was called journalists initially asked if it would be the “climate election”. They then failed to live up to their own promise. The climate crisis is already part of the election – it’s time the media treated it that way.

• Stephen Buranyi is a writer in London