'I made excuses': music industry frets over becoming carbon neutral

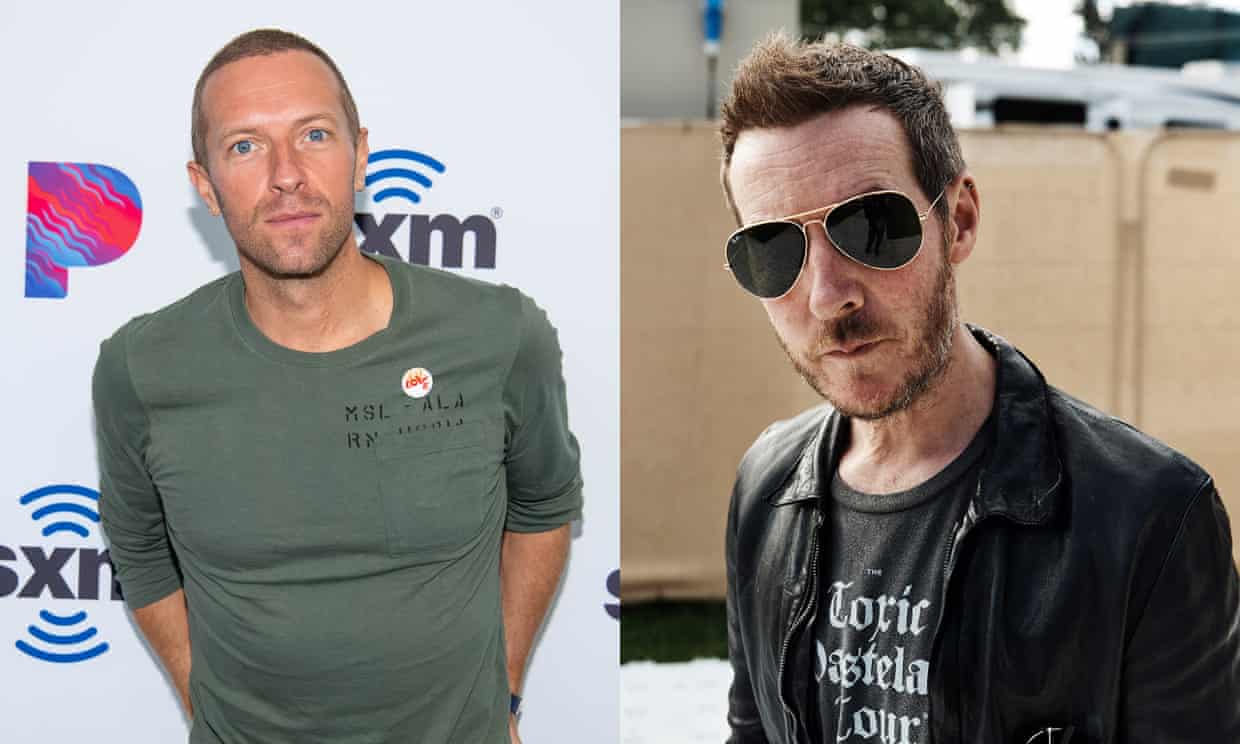

by Lowri EllcockColdplay and Massive Attack have pledged greener tours – but is the billion-pound gigging industry compatible with eco activism?

As they released their eighth album, Everyday Life, Coldplay announced last week that they would not be taking it on tour, instead performing the album just once on British soil at the Natural History Museum. Frontman Chris Martin expressed his concerns about the future of touring, highlighting the difficulties of reconciling flying with environmentalism and expressed a wish to see a Coldplay show run largely on solar power with no single-use plastic. Snark was instant – “Coldplay announces plan to spare planet the effects of future Coldplay concerts” ran one headline – but others lauded the move: the band’s previous tour featured 122 shows across five continents and generated £405m.

Massive Attack also declared this week that “business as usual is over’’ as they begin working with the University of Manchester’s Tyndall Centre to map the carbon footprint of tours and work on a blueprint to reform the industry, a message similarly shared by Billy Bragg on his recent tour.

Bragg tells me: “I looked at what I do and thought, how can I do this in a way that is more conducive to a greener way of touring?” As well as raising the issue at his shows he now limits his flights through a new touring model: Bragg is the only member of his crew to fly to the US, where he then drives from venue to venue with a small team, settling in each city for a number of shows.

Chiara Badiali, from UK based music and sustainability charity Julie’s Bicycle, says “reimagining touring is probably the music industry’s biggest challenge – it will have to change”, while Lewis Jamieson, a founder member of UK climate action group Music Declares Emergency, backed Coldplay’s action. “If they can create a template for touring that is more sustainable,” says Jamieson, “they are in a position where they can drive that research more than smaller acts – something that will benefit all artists.”

But gigging is more important than ever to artists in the age of streaming and rapidly declining CD sales – and especially for those who are not industry juggernauts. It was reported last week that the value of the British live music industry reached a record high of £1.1bn in 2018. Is radical change possible?

Writing in the Guardian, Massive Attack’s Robert Del Naja admitted that bands won’t completely stop touring. Fay Milton, co-founder of Music Declares Emergency and member of British post-punk group Savages, agrees: “Music, playing music and sharing culture is a beautiful and amazing thing and we shouldn’t stop that altogether.” This was reiterated by Jamieson, who declared the end of live music “neither feasible nor desirable”.

Bragg says: “There’s something that you can get at a gig that you can’t get online. It’s a form of communion. That feeling of not being alone, there’s not many places you can get that any more.”

Milton acknowledges she contrived explanations while touring. “I was really aware that we were heading towards climate catastrophe but I made excuses because it was art and I saw it as different,” she says. “But no one really gets special dispensation. This is something we all need to do.” Milton says she doesn’t know if she’ll enjoy touring any more, without feeling the weight of it.

Coldplay and Massive Attack are not the only acts to address these matters. In 2010, Drake billed his Away from Home tour as half tour, half environmental campaign, working with not-for-profit organisation Reverb to minimise the tour’s environmental impact. Reverb has since grown, working with Pink, Fleetwood Mac, Harry Styles and Maroon 5 in the last year alone, and Billie Eilish’s tour in 2020 will also be in partnership with the company. Eilish expressed her support for climate activism in a video entitled Our House Is on Fire and earlier this week wore a “No Music on a Dead Planet” T-shirt at the American Music awards – the same slogan touted by Foals at this year’s Mercury prize ceremony.

Much of the efforts of Reverb and its affliated artists’ focus on actions such as limiting the use of plastic straws, providing water for reusable bottles and educational hubs around the venue – actions that align closely with Music Declares Emergency’s plan. However, far more work is needed to tackle the larger contributing factors relating to climate change and the entertainment industry. The Green Touring Network report that 34% of a tour’s carbon footprint comes from the venue itself, followed closely by audience travel (33%), with the third biggest factor being merchandise at 12%.

The 1975 have addressed the merch question in an easy but somewhat radical step: “upcycling” unsold previous merchandise by applying new graphics. As well as focusing on recycling and waste reduction backstage, Mumford and Sons reported – somewhat vaguely – that they worked to reduce the carbon footprint of their recent tour. KT Tunstall took the more direct approach of planting thousands of trees, a move similarly adopted by Coldplay in 2002. But carbon offsetting was criticised by Del Naja, who said it “creates an illusion that high-carbon activities enjoyed by wealthier individuals can continue, by transferring the burden of action and sacrifice to others”. Tours will need to not generate CO2 in the first place, and there will need to be pressure from artists and promoters on venues to switch to sustainable energy sources – or face losing their business.

There are more radical solutions besides, particularly regarding audience travel. Milton argues that live music “doesn’t have to be commercial or something you do on stage, it can be a lot more participatory as well. There’s a lot of interesting technology there.”

MelodyVR allows fans not attending a gig to watch it via a virtual reality headset and app. “Instead of a 50-day tour, some artists prefer to do five and share it via VR,” says Anthony Matchett, MelodyVR’s CEO and founder. Another potential solution could be livestreaming performances to cinemas, as Kanye West did for the recent launch of his album Jesus Is King. Bragg resists ideas like this though, complaining that “so many people experience culture through a screen in isolation”.

The passion for live music is unlikely to abate, then, for artists or audiences. The key challenge, as Jamieson says, is “to find ways of doing things better first, rather than assuming that the only way is to stop doing them”.