Central African Republic seeks a salve for the scars of war

by Jack LoshConflict-ravaged country hopes trials at new court in Bangui will at last punish those responsible for massacres and rape

The moment they entered town, the rebel soldiers started firing on civilians. As terrified crowds fled into nearby woods, a 40-year-old disabled woman called Monique Douma realised she was trapped.

“I told Monique to come with me but she said she couldn’t,” a relative later told investigators. “She said: ‘I don’t have the strength to run.’” Militants set fire to Douma’s home while she hid inside.

This massacre in Central African Republic (CAR) unfolded in May alongside coordinated attacks on two neighbouring villages in Ouham-Pendé prefecture. Fighters from the 3R armed group tied up and then killed dozens of men. Douma suffered fatal injuries in the blaze; the body of a 10-year-old girl was later found with a single bullet to her head.

By the end of it, at least 46 civilians were dead. Many of the militants remain free.

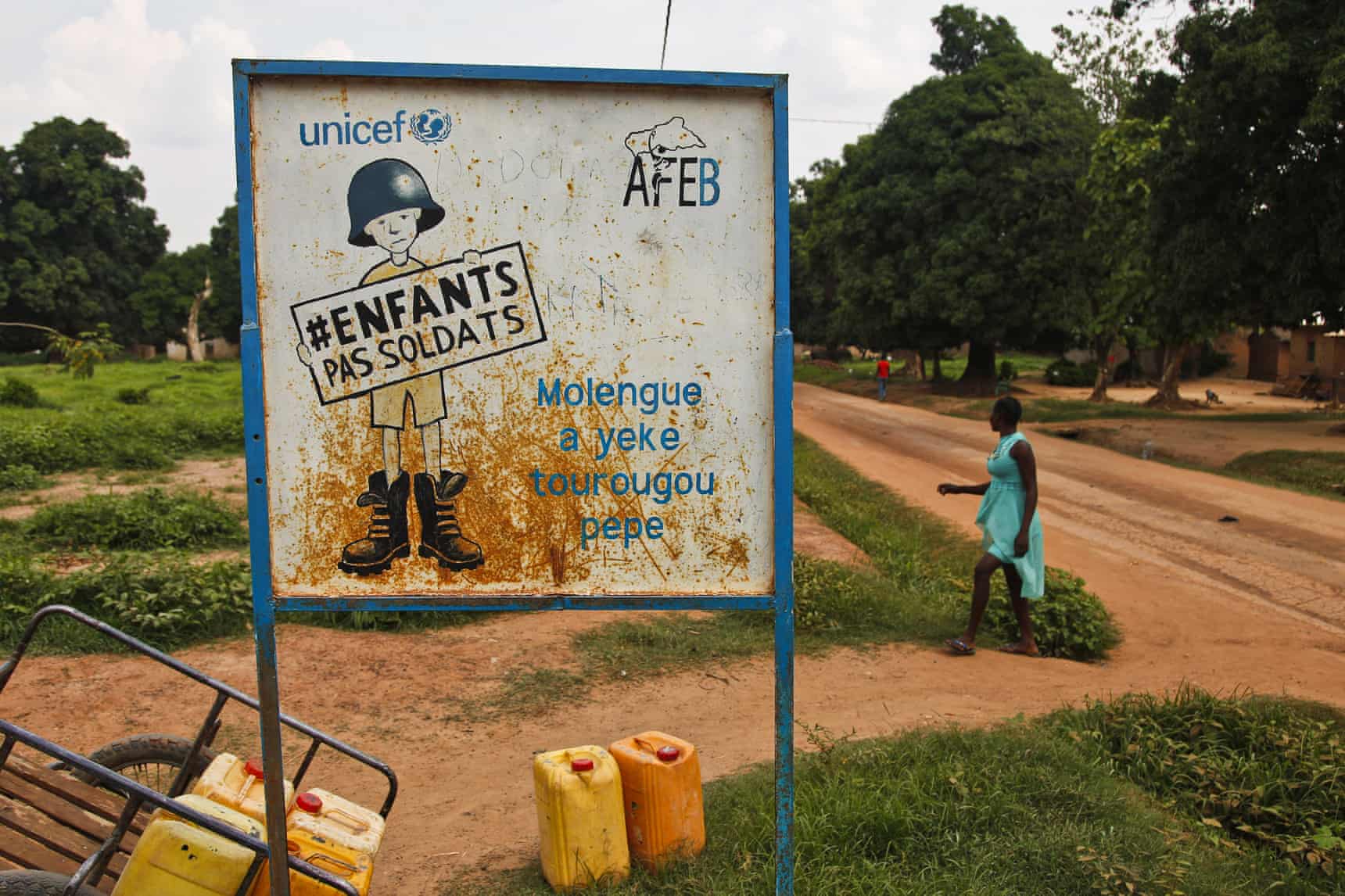

The harrowing attack in the country’s north-west is just one of many to have ravaged CAR since civil war erupted in 2013, often with no consequence for the culprits. Corrupt, dysfunctional courts mean that thousands of victims of brutality are routinely denied justice.

About 300 miles away, a new development in the capital, Bangui, could signal a change. On Rue Martin Luther King Jr, behind a concrete wall painted with the scales of justice, a courthouse is being overhauled. Ringed by razor wire, this construction site is part of a bold experiment to begin to pull this crisis zone back from the brink.

To be known as the special criminal court (SCC), an ambitious institution is being set up in a country scarred by ethnic cleansing and war crimes, the lead actors of which remain at large. The violence stretches back to 2003, when General François Bozizé seized power in a violent coup that sparked severe unrest.

In 2013, when Muslim Seleka rebels overthrew Bozizé, prompting Christian anti-balaka militias to rise up, the country was thrown into a period of reprisal killings, widespread rapes and mass displacement.

After years of Bozizé’s authoritarian rule, what was left of CAR’s justice system collapsed.

This February, rebel groups and the government signed a peace deal – the eighth attempt to resolve the six-year conflict. Nine months on, violence involving signatories of the treaty is rising. Clashes between two armed groups called the FPRC and MLCJ in the north-east have displaced more than 24,000 people. Another group, the UPC, has advanced into south-eastern areas, breaching the ceasefire, drawing condemnation from the UN and raising tensions with local anti-balaka militants.

Prosecutors at the embryonic SCC are now tasked with indicting militants for crimes in CAR since the 2003 coup, and hope their endeavours will mark the denouement of this bloody tragedy, fuelled in part by a culture of impunity. They are progressing with multiple investigations, including one into the massacre in Ouham-Pendé in May.

It is hoped trials will start in 2021. By bringing warlords to justice, the plan is to usher in a new era of accountability that deters militants from launching more attacks.

Since the 1990s, CAR has hosted roughly a dozen different peacekeeping and special political missions; this new court is just the latest experiment in the country’s “laboratory for international peacebuilding initiatives”, to use Yale anthropologist Louisa Lombard’s phrase. While similar tribunals elsewhere have judged alleged war criminals from Cambodia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and the former Yugoslavia, this one would be the first UN-backed court established inside a country where fighting continues.

But huge challenges remain.

“The special criminal court is an unprecedented effort to deliver much-sought justice for brutal, widespread crimes committed with impunity in the country,” says Elise Keppler, associate international justice director at Human Rights Watch (HRW). “The court, with its combination of international and domestic judges and prosecutors, also holds promise as a potential model for other countries.”

Legal gears elsewhere are also starting to turn. Two alleged anti-balaka chiefs – one of them prominent in African football, the other a politician nicknamed Rambo – have appeared at the international criminal court (ICC) in The Hague. Prosecutors accuse Patrice-Edouard Ngaissona and Alfred Yekatom of commanding armed groups against CAR’s Muslim population, using murder, torture and child soldiers. Both have denied wrongdoing.

Judges there are deciding if there is enough evidence to move forward with a trial, which could be the first of many to emerge from CAR’s years of bloodshed. “This case will not be the last one,” said the ICC’s chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, at the end of a preliminary hearing last month. “I am investigating all sides in the conflict.”

In September, a national court in Bangui secured the first conviction of a former Seleka rebel commander, jailing Abdoulaye Alkali-Saïd for crimes against humanity. While his sentence of just six years – and the breakneck speed of his trial – raised some eyebrows, the prosecution of a high-ranking militant who had targeted civilians was hailed as a positive step.

“This is the fight against impunity,” says the country’s attorney general, Eric Didier Tambo. “If the ICC can catch some big fish, we too are catching other fish.”

February’s peace agreement also raised hopes of establishing a long-awaited truth and reconciliation commission, but this has still not got off the ground.

The SCC is a hybrid court of national and international elements. Consultants are sourced from western countries; donors include France, Holland, the EU and the US. But its creators are keen not to be seen as meddling foreigners in this former French colony, weary of decades-long exploitation and outside interference, and trials will follow CAR’s national legislation, with more than half of the court’s 25 magistrates hired locally.

The SCC’s precarious funding model was highlighted by a recent HRW report that uncovered a gap of approximately $1m (£775,000) for 2019 operations, with no money pledged for future years. The anticipated costs are about $12.4m a year. This year’s gap has since been plugged, but sources say a further $5m is needed for 2020.

The HRW report also warned about staff shortages, which have held up important activities, and urged existing officials to intensify investigations.

CAR’s UN peacekeeping mission, known by its acronym Minusca, is a key player in efforts to reform the justice sector, having rehabilitated 24 courts and prisons.

But insiders also describe bureaucratic tussling at the SCC between court staff and managers at Minusca and the UN Development Programme, with red tape impeding staff’s ability to work on their own initiative.

“No one group is governing the court single-handedly, but everyone involved in it has something to say,” says a senior western contractor who requested anonymity in order to speak freely. “Minusca talks about making the court more independent, but they interfere in everything.”

Vladimir Monteiro, Minusca’s spokesman, says the mission is developing a strategy to improve the court’s autonomy, adding that Minusca “continues to bridge gaps that cannot be otherwise filled”.

CAR is awash with weapons, and armed groups control approximately three-quarters of the country, so robust protection for witnesses is imperative. Without reliable law enforcement, the court is developing its own system, although “further progress is needed”, adds the HRW report.

Facilities for detaining high-risk suspects are limited, and beset by overcrowding. Nor has secure accommodation been provided to most of the SCC’s domestic judges, leaving them vulnerable to intimidation. Investigators will need to rely on UN peacekeepers for security, making it hard to operate discreetly. An SCC spokesperson did not respond to requests for comment.

Even as the war cools down, the court faces a country where years of widespread violence have ravaged its social fabric, normalising sexual exploitation and increasing the prevalence of domestic abuse. Once a conflict ends, explains Madeleine Rees, secretary general of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, it can be “very difficult to switch back to constrained behaviour regulated by law”. The roots of wartime sexual violence lie in social inequality that predate the outbreak of hostilities. “It starts in the household and it spreads then into society more broadly,” says Rees. “When you get an armed conflict, the sorts of violence that were perpetrated before then get meted out more.”

Despite all the challenges, there is a strong desire to see the SCC succeed. Mike Cole, chief of the ICC country office in CAR, said the court could be a catalyst for justice reform. From hiring interpreters to keeping evidence safe, the SCC promises to put in place “all those rather dull and boring but incredibly important justice-related capacities that any normal, functioning court would have”, he says.

“After cases have come and gone,” adds Cole, formerly of the British army legal services branch, “the transfer of that real capacity into the national system is a potential huge legacy, regardless of the outcome of any cases.”

For now, as rounds of rough justice continue, survivors have little prospect of seeing the guilty in court.