In full flow: art, history and nature on the River Wye

by Kevin RushbyAlmost 250 years ago an Anglican cleric’s enthusiasm for the river’s beauty changed the way we travel. Canoeing it proves a great way to celebrate his pioneering legacy

It’s not often that I find myself expressing gratitude to an 18th-century vicar, but as our canoe slides forward into the great river bend I silently thank one William Gilpin. To our left a jungle of ancient trees rises to impressive crags; to the right there are meadows and lower hills. In the skies above a lone buzzard sails over.

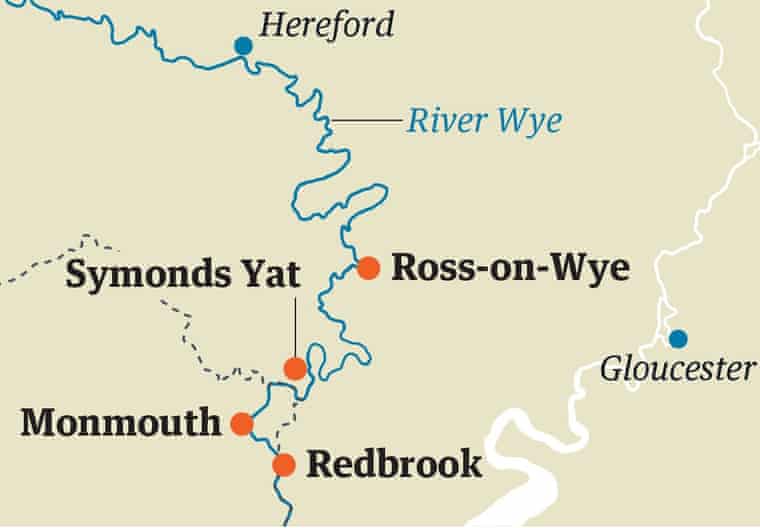

“That’s the famous viewpoint,” says Stuart, our guide, pointing up to the ridge above the crags, “Symonds Yat. Beyond that we’ve got the rapids, then one of the sections I like best: the Slaughter, a huge curve of river with deep forest on both sides.”

Without Gilpin the conversation might be very different. The crags would be ghastly, the forest dark and depressing, the rapids impassable and Stuart would have been dubbed a dangerous lunatic for dragging travellers like son Niall and me to such an awful place.

Gilpin, you see, was a pioneer in seeing the beauty in raw, natural places, especially here on the River Wye. Without him and a few other romantic souls, we might all be bloodless scaredy-cats hiding in our drawing rooms and admiring the wallpaper. In 1770, he set out on a tour of the River Wye, an expedition that would lead to his book, Observations on the River Wye, and trigger not only a wave of tourism to the river but also tutor the public in how to look at what lay in front of them. In many ways, 2020 marks the 250th anniversary of both tourism in Britain and the ways we enjoy the British countryside: a year of celebrations is planned all down the river. (See the excellent PDF on Gilpin and the Picturesque Wye Tour.)

By modern standards Gilpin’s prose reads like a sermon, but at the time his delight in wild “declivities” and “splendid ruins” was revolutionary. Writers and artists flooded in. Coleridge blessed Gilpin for alerting us to the “loveliness and wonders of the world”, while at Tintern Abbey, Wordsworth enjoyed one of his “spots of time”, a moment of ecstatic bliss in nature.

O sylvan Wye! thou wanderer thro’ the woods,

How often has my spirit turned to thee!

Our own attempt to reach a state of bliss on the Wye has been delayed by rain and flood. The first day’s canoeing is cancelled so we drive from the first campsite to the second, outside the White Lion Inn in Ross-on-Wye. At least we might still get two days on the water.

The White Lion, I have to say, is about as good a campsite as you would hope for: a flat green lawn between a decent pub and a beautiful river, beside a 15th-century pink stone bridge whose arches are being swooped by swallows and martens. (In winter the campsite is closed – reopens 15 March, £10pp – but the pub has rooms, doubles £75 B&B.) We walk around Ross, a mix of ancient half-timbered palaces and modern shops. What would Gilpin say? Actually, he grumbles that the town has no view worthy of his ultimate accolade – “picturesque”.

“It has no characteristic objects,” he laments. “It has too many broken parts; it [the view] is seen from too high a point.” We leave the old curmudgeon grumbling in the churchyard and go for a pizza.

Next morning Stuart decides that the river level has dropped sufficiently and we set out from below the town, paddling and drifting quickly downstream. The banks are invisible, trees surrounded by gurgles of muddy water. Eventually we are into the long sweeping bends that curl around Symonds Yat, a lovely section of river that leads to the Old Ferrie Inn for a late lunch. Beyond that it’s a short paddle to our overnight stop, the Saracens Head (doubles from £100 B&B), a pub that has a hand-pulled ferry, as well as beer. Niall and I take the chance to yomp up the hill through the woods, emerging at the celebrated viewpoint.

Amid crowds of people at the top, we watch the late sun silver the river far below. It is the most magnificent view, even if Gilpin’s fastidious eye is appalled by rocks unadorned by moss or lichen. Better for climbing, I say. There are even some buried in soil, a thing of particular distaste for the reverend. “Lumpish and the least picturesque,” he sneers.

Then, miraculously, the babble of voices subsides and we have the place to ourselves. Niall spots a peregrine, shooting across the sky like a meteorite, then banking and abruptly diving with breathtaking speed. It is like one of Wordsworth’s spots of time, indelibly imprinted on my memory, and experienced where the poet himself had stood over 200 years ago.

Next morning, we begin with a treat: the rapids. Actually with the river so high, Stuart warns us, it won’t be as “interesting” as normal. Nevertheless, the buildup is impressive: the river narrows, the water goes glassy and thoughtful, then suddenly develops a frown, which we begin to speed down, bouncing through the waves. There’s just time to think, “I’m actually glad the water was this high,” before we are spat out into peaceful pools.

Next we enter the Slaughter, an idyllic sweep of river that passes through deep ancient forest where, in 911 AD, a Viking army under Eric Bloodaxe was trapped and massacred. These days the only marauders you might encounter are wild boar. It’s a wonder no one thought to slaughter the dogmatic Gilpin here, as he sat bolt upright and pontificated about how to enjoy looking at stuff. He generously allows that nature is an adequate “colourist”, but complains of her inability to produce harmony, often misplacing a tree or rock, something he would correct in his paintings. No wonder Jane Austen had fun lampooning him.

Stuart, by contrast, is a fine companion, keeping us amused as we tackle a tricky headwind to reach Monmouth. From there, a few gentle curves bring us to our finish in the village of Redbrook on the Gloucestershire bank of the river. We are right under the old railway viaduct, which is now a footpath leading to the Boat Inn.

Gilpin is strangely silent on the picturesque qualities of a pint glass filled with foaming amber liquid. We slip away while he’s moaning about the foreground trees and head for the bar. Stuart has a story about how his dog ate a Land Rover’s back seat that I want to hear.

• The trip was provided by: Wye Canoes, which hires two-person canoes for £50 per day and runs guided trips starting at £80pp per day; the Saracens Head Inn (see above); and Wye Valley & Forest of Dean Tourism

Looking for a holiday with a difference? Browse Guardian Holidays to see a range of fantastic trips