Party lines: five writers' verdicts on the election manifestos

by Charlotte Higgins, Sam Leith, William Davies, Joe Dunthorne, Nesrine MalikTime for ‘real change’? ‘Unleash’ Britain’s potential? And what does ‘Wales, it’s us’ mean? Five writers tear apart the party manifestos to show what they’re actually saying

‘Page 54 is the “fuck you, Rory Stewart” page’: Charlotte Higgins on the Conservatives

In a volume of absolute zingers, my favourite passage in the 2019 Conservative manifesto, Get Brexit Done, is on page 54. I’m thinking of it as the “fuck you, Rory Stewart” page, since it shows a photograph of the new candidate for Stewart’s constituency, Penrith and the Border. This wholesome-looking chap is a vet, and he is pictured cheek to cheek with a black labrador – the second-poshest dog breed in Britain, after the chocolate lab, as any reader of Tatler knows. The canine has a melting eye, an alert ear and, probably a quivering, damp nose, but the face is cropped tightly, perhaps in case he or she is a secret Lib Dem supporter. Page 54, fittingly, is the animal welfare page – even the crisp 1979 Conservative manifesto had an animal welfare section. In it we are told that the Tories “will crack down on the illegal smuggling of dogs and puppies”. It is in those two words “and puppies” that the true force of this document resides. “Conservatives: kind to puppies!” might be its tagline – a work, taken as a whole, of stomach-churning intellectual dishonesty.

The content of the Conservative manifesto has been pored over by policy experts. But information is also stored in its language and rhetoric, its presentation and expression. Looking at the document this way, it is clear that the ghost of 2017 is utterly banished. That ill-fated document resembled the prospectus of an academically middling boarding school: its title, Forward, Together (in which that prissy little comma did so much work) might have doubled for the school song. The prevailing colour was a sober navy, and the very typeface, with its mature serifs, radiated head-girl vibes. There were no pictures, bar one of Theresa May attempting to channel “strong and stable”. Its spirit could be summed up as, “We must revise very hard for our Brexit A-level.”

In 2019, by contrast, the school is St Custard’s, the spirit, Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle’s Whizz for Atomms. Johnson’s introduction reeks of the columns he poured so much work and time into. “For the last three-and-a-half years, this country has felt trapped, like a lion in a cage. We have all shared the same frustration, like some super-green supercar blocked in the traffic.” This is Boris “being Boris”, dangling, metaphorically, from his zip wire, his mind mechanically plotting three steps ahead even as he cynically invites his audience to laugh at him. The opening photograph shows Johnson doing a thumbs-up – brazenly echoing Donald Trump’s trademark gesture. Yes, this photo subliminally reminds us, this man has a phallus and, what’s more, he intends to use it. What Johnson wants us, the electorate, to do, we are told, is “unleash” Britain’s potential. The word “unleash” occurs in the manifesto 17 times. All I can hear with this unleashing of dangerous animals is Shakespeare’s “let slip the dogs of war”, but never mind. Let the blond lion, or should that be hulk, out of his cage! ROAR! PHWOAR!

Those Tory MPs who have “devoted themselves to thwarting the democratic decision of the British people” have been, we are to understand, purged and replaced by bright and shiny new candidates, the most choice of whom are pictured. These include a nurse of colour, an ex-RAF squadron leader of colour, a smattering of GPs, some ex-cops, a female engineer pointing meaningfully at what appears to be a spread from the Innovations catalogue, and a primary school teacher building a new Britain from some brightly coloured blocks with an actual child – double points. They are designed, of course, to suppress thoughts of Eton and the Bullingdon and Jacob Rees-Mogg. They are interspersed with more photos of Johnson, bringing opportunities here for leader-photo bingo – we find him variously on his bike, in a hi-vis jacket, with some cops, with some soldiers, with a nurse, and, finally, in a distillery, looking as if he’s trying to organise a piss-up in it.

All of this one-nation imagery cloaks, or attempts to cloak, the fact that the manifesto is built on premises of such astounding falseness that it is as if its writers have slipped through some rent in the fabric of reality. The ghastly state of Britain’s high streets, for example, with their “boarded up department stores, shops and pubs” is presented as if it were some other party, rather than the Conservatives themselves, who have been in charge these past nine years. Occasionally, the real worldview slips through the disguise. “We will ... end the blight of rough sleeping,” we are told. Leaving aside the fact that the rise in homelessness is a result of Conservative public-spending cuts, it’s the word “blight” that is worthy of attention. A “blight”, in this sense, is an eyesore, something that ruins the view. Rough sleeping is not a “blight” for those actually existing without a roof over their heads; it is only a “blight” for those looking on, for those stepping past the sleeping bags. Still, it’s good to know in whose interests the Tories propose to act.

The falsest of the false premises, of course, is that Getting Brexit Done (which appears, with its cognates, 87 times in the document) is a singular act that can be achieved at a stroke, rather than a painful and complex process that, if it occurs, will take years if not decades to effect. In a single phrase resides a world of shameless dishonesty. But that, sadly, is what we have come to expect.

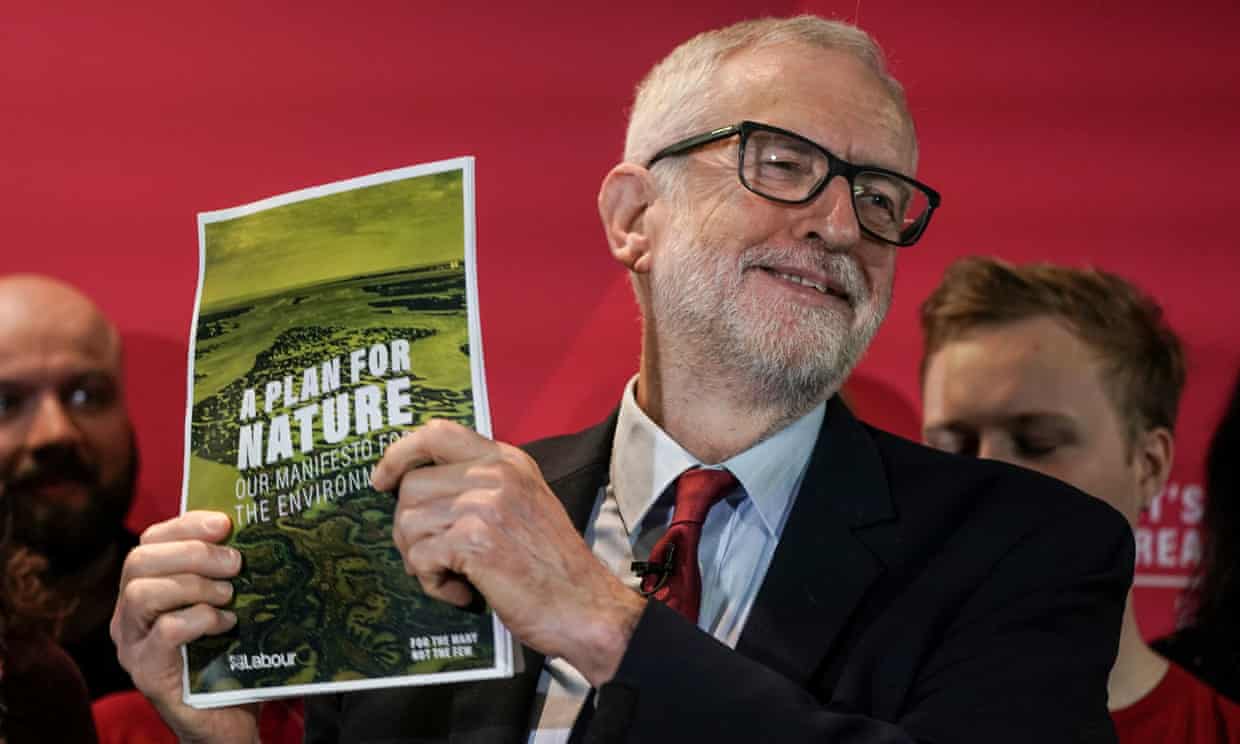

‘A startlingly radical manifesto’: William Davies on Labour

It’s Time for Real Change – the title of Labour’s manifesto raises the question: what does “unreal” change look like? Some of the connotations are easy to discern. The party’s opponents are led by a man famously divorced from reality, in terms of both his personal privileges and his contempt for facts. Then there is Brexit. Nobody doubts that will be a real change, but it won’t be the heroic one that exists in the fantasies of Daniel Hannan.

But there is a deeper meaning to this slogan, which emerges over the course of the manifesto. The tragedy of the decade that followed the financial crisis was that “real change” never occurred. More drastically, and in ways that historians will find baffling and appalling, the discovery of anthropogenic global warming (known to Exxon in the 1970s, and firmly on the policy agenda by the 90s) has still not been met by “real change” in rates of carbon dioxide emissions, save for a continued upturn.

Dating back to the 19th century, major crises of capitalism have usually been the basis for some kind of social and political renewal, even if there is considerable pain along the way. Labour, understandably, points to 1945 as the premier example. The gambit of this manifesto is a little more complicated, in that it’s precisely the absence of a serious rupture in the status quo that needs fixing. Britain desperately needs a genuine crisis, in the strict sense of a turning point.

Labour’s central aim is to use the impending ecological catastrophe as a basis for this rupture and renewal. The title of the manifesto’s opening chapter is “A Green Industrial Revolution”, and a great deal hangs on its fusing of economic and environmental policy. “The climate and environmental emergency is a chance to unite the country,” it argues, “to face this common challenge by mobilising all our national resources, both financial and human.” The scale of ambition is audacious and entirely in keeping with the scientific consensus on climate. To encounter the phrase “the mistakes of the carbon era” in a mainstream policy manifesto is astonishing. So that’s what real change means: escaping a 200-year-old energy paradigm.

The question is whether a new government can achieve change and national purpose on a scale usually triggered only by war or wholesale economic collapse. The authors of this manifesto have clearly decided that Labour and Britain have nothing to lose in trying. The entire force of the state is being hurled at Britain’s decaying social infrastructure. “We will act on every front to bring the cost of housing down and standards up, so that everyone has a decent, affordable place to call home.” As in previous times of national emergency, this state will muddy its hands in all those areas that were left to the market after the 1970s, in building, innovating, upgrading and above all investing.

The watchword is “invest”. There are echoes of Gordon Brown’s rhetoric as Labour chancellor, from the years when economic stability and low interest rates were heralded as an unprecedented golden age for both private and public sector investment, only now Labour intends to specify where the investment will go. Individual technologies are named (“heat pumps”, “gigafactories”) offering a clear signal that the supremacy of the market is over. With a national investment bank and a sustainable investment board, we will “invest in children’s oral health”, “invest in more county farms”, “invest to make our local roads, pavements and cycle-ways safer”.

When Labour aren’t “investing” for the future, they are “tackling”, “scrapping” and “banning” the harms of the past. Promises to scrap universal credit, Ofsted, tuition fees and the “bedroom tax”, and to ban zero-hours contracts, have already received attention. But the list of things to be “tackled” is far more extensive, from late payments to small businesses, to the cost of school uniforms, to regulatory capture by big business. Labour has been questioned on whether the investment plan in its manifesto is deliverable, but perhaps the greater risk is that, in its devotion to recognising the manifold injustices and injuries of everyday life in Britain today, it pledges to eradicate every perceived unfairness in society, through sheer force of central government will.

This is in the nature of any left-populist agenda. What Labour correctly understands is that, while Brexit has vast macroeconomic and geopolitical implications, the disaffection that caused it is often intensely personal and local. People feel that their town and neighbourhood have been neglected for many years. Corbyn’s main strength as a leader is that (at least among those who don’t despise him) people feel he cares about everyday struggles. By the same token, It’s Time for Real Change speaks to a melancholic sense of neglect and abandonment, especially outside the south-east of England. Recognising past suffering is admirable and necessary, but the far more daunting task is in leaving it behind and embracing the kind of future that Labour is now offering instead. Huge levels of trust will be required, if this journey from melancholia to “real change” is to be completed.

That this is a startlingly radical manifesto is partly due to the amount of time that has already been wasted. It promises serious corporate governance reforms, to give employees a voice and ownership rights within companies, of the sort that were toyed with by New Labour and then dropped in the mid-1990s. It pledges rights to private renters, of a kind that are a basic feature of civil society in countries such as the Netherlands and Germany. And above all, it presents a mainstream party finally getting the measure of the severity of global environmental catastrophe. It is a litany of goals and ambitions that would stretch Britain’s public administration to its absolute limit. But the message – “real change” – is ultimately one of residual hope: that it’s still not too late.

‘A right boggins’: Sam Leith on the Liberal Democrats

The imperative mood of the Lib Dem manifesto is in line with slogans such as “Take Back Control”, “Get Brexit Done” and “Make America Great Again”. The title, rousingly unambiguously, is Stop Brexit. The subtitle is also decently turned. “Build a Brighter Future”, cliched though it is, alliterates and trips pleasantly off the tongue. A trochaic trimeter. We’re not just about stopping nasty things, it tells us, but about doing nice things afterwards.

So, top marks for the first six words. I give those words this close consideration because inside, I’m afraid – on a purely literary and rhetorical level – it’s a right boggins.

Paragraph one gives us “brighter future”, “ambitious vision”, “future generations”. Paragraph two gives us “positive vision” and “brighter future”. And on it goes: “our children’s futures”, “the kind of country and society we deserve”, “seismic change”, “hope, not fear”, “a brighter future for everyone”, “build that brighter future”.

The introduction, in slightly eccentric order and proportion, just about sets out some of the themes of what’s to follow – among them the “£50bn Remain Bonus”, of which oddly little is later made. It gives us two paragraphs on how a Lib Dem government will “save the planet”, two on education, one on childcare, two on in-work education, a single sentence on “reinventing the relationship between business and the communities in which they operate”, and then three paragraphs on mental health. “This,” it concludes, “is the Liberal Democrat plan for a brighter future.”

The main body of the manifesto that follows is hard to navigate. One moment we are reading pure rhetorical woo and the next a detailed policy point, often in the same sentence. Common sense seems to suggest that you make the granular stuff super-clear and logically structured, and save the woo for the exordium and the peroration. Who do you imagine is the person reading page 78?

After we’ve had “Stop Brexit”, the main headings all begin “Our Plan” – “For a Stronger Economy”, “For Better Education and Skills”, “To Build a Fair Society”, “For Freedom, Rights and Equality”, “For a Better World” and so on, which roughly correspond to areas of policy – but within them it sometimes seems pretty random. In one paragraph you’re reading approvingly about plans to devolve air passenger duty in Wales and put Cardiff airport on a level playing field with other regional airports. In the next you’re reading about safeguarding peace in Northern Ireland. Under “Help to Stay Healthy”, there’s a burst of bullet points about food and tobacco, then a burst of bullet points about drugs policy, then almost as an afterthought a section on reproductive rights.

The main organisational trick – a cousin of the old rhetorical figure of enumeratio, or the numbered list – is that use of bullet points. But bullet points are there to sharpen the reader’s concentration, to point up distinctions and categories. When some bullet points are unmarked subcategories of other bullet points, when they are longish unmemorable sentences, or when you have fully 19 of them in a row under a single subject area, you might as well set the thing as continuous prose. And there’s just not much zing. Which editor passes a sentence like this? “Reform fiduciary duty and company purpose rules to ensure that all large companies have a formal statement of corporate purpose, including considerations such as employee welfare, environmental standards, community benefit and ethical practice, alongside benefit to shareholders, and that they report formally on the wider impact of the business on society and the environment.”

There are some admirable policies in here. But the ordinary voter shouldn’t have to wait for newspaper explainers to be able easily to understand what those key policies are.

‘No shortage of overworked phrases’: Nesrine Malik on the Green party and Brexit party

The title of the Green party manifesto is a rousing If Not Now, When?. But everything else seems short on rhetoric or stylistic flourishes. It reads like a manual rather than a call to arms. True, the foreword has a stirring tone. “The next ten years are probably the most important in our history. At this time of crisis, we cannot go on as we are.” But it is clear that the urgency the party believes underscores its mission discourages too many emotional hooks.

The party’s “Green New Deal’, a 10-year plan, is laid out in short staccato sentences, ones that address the reader directly with repetitious deployment of the “only party you can trust” line. Time and the shortness of it is the connective tissue here; the words “it is time” introduce most of the policies set out in the document. There is a risk, for all the reiteration of the danger, that one can come away thinking that it is already too late and there is little that can be done to stave off the climate emergency – that the task is prohibitively difficult. A section entitled “Elected Greens Delivering” appears to be designed to offset this, by providing examples of wins already secured by elected members of the Green party. Another feature is a refreshing restraint when addressing the Greens’ rival: large corporations. There is no demonising language or conspiracy cliches about “Big” anything. Large corporations come into the spotlight only when asked to pay their “fair share”, another phrase that punctuates the manifesto.

That restraint falls away with Brexit. The Green manifesto loses its stride when it touches on this issue, a reflection of how the topic has sucked too much air out of British politics. It is impossible to ignore but, to the Greens, understandably seems like a distraction. After the initial mention of Brexit, which the foreword claims “hangs over us”, in a country where “democracy is under attack”, it is not mentioned again until page 29, and with it hackneyed expressions come in a rush. The power game is “rigged”. The way forward is to choose “project hope” over “project fear”. The subtext is clear: the really pressing issue is much bigger; a planetary crisis is occurring.

There is no shortage of such overworked phrases in the Brexit party “contract” with the people – its version of a manifesto – which one can sign electronically. “The will of the people” makes an entrance in paragraph one. “The People” from then on is capitalised – but not, curiously, in the phrase “the will of the people”. The arbitrary rendering of proper nouns continues throughout the contract. So “Citizens” is capitalised but so are “Universities” and the “High Street”. What is being signposted as a political concept as a result becomes confused. The sentences can be chatty – “This is our money anyway,” says the section on maintaining grants by the EU to UK businesses – while the name of the party’s programme, “A Clean-Break Brexit”, dispenses with political poetry. If the contract has a “sound”, it is that of a high-emotion campaigner making a pitch to the voter on the doorstep, determinedly counting off their political arguments on their fingers.

Unsurprisingly the document presses into service the familiar rhetoric of reaction, a narrative of subordination to and reclamation from the “Establishment”, one that includes both Westminster and the EU. Its bromide populism doesn’t disguise its phoneyness. This is a single-issue party, and the passages on other concerns seem, even by the contract’s own standards, artless and rushed. To the Green party, Brexit is a distraction. To the narrow minds of the Brexit party, the distraction is everything else.

‘It’s hard to trust a slogan that contains so much punctuation’: Joe Dunthorne on Plaid Cymru and SNP

In Welsh, the Plaid Cymru slogan is “Ni yw Cymru” which means: “We are Wales.” It’s simple, powerful and establishes the idea that the nation is speaking with one voice. Their English slogan, however, is much more clumsy. They’ve gone with: “Wales, it’s us.” It’s hard to trust a slogan that contains so much punctuation. I also can’t help feeling that – perhaps at a subconscious level – the decision to make their English language slogan significantly more ugly than the Welsh one might be sending a message to non-Welsh-speaking voters. A recent study showed that Wales was tipped into voting for Brexit thanks to the influence of English settlers who have moved there. In which case, “Wales, it’s us” might be speaking on their behalf and so would more truthfully mean: “Wales, it’s us, the English, and we’re destroying you from the inside.”

From a literary perspective, the most notable thing about the Plaid Cymru campaign slogan is that it’s written in the first person plural: the “we” voice. If one of my students were to use first person plural in a creative writing class, then we’d undoubtedly end up talking about the most famous contemporary usage of that perspective: The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides. That novel is narrated from the shared perspective of five young boys who watch, with a mixture of admiration and horror, as their neighbours steadily and systematically kill themselves. Nobody knows why it’s happening. All attempts to make sense of it fail. And in the end, having become complicit in their neighbours’ deaths, the boys lives are ruined, too. If this is not a metaphor for the Welsh experience of Brexit then I don’t know what is.

In his statement, party leader Adam Price builds on this doomed atmosphere, saying that Wales is being “offered a poisoned chalice” in the choice between the two main parties in Westminster. Poisoned chalice is a cliche so perhaps he should have gone for something more fresh: that the thank you flowers that Westminster sent carry a strong whiff of ricin? That many of the chocolates in the Quality Street box are shaped like little pills?

As writers of murder mysteries know, you can indicate the presence of cyanide by having your character notice the scent of bitter almonds. Imagine that smell rising from one particular present beneath the Christmas tree. We turn over the label and it says: “Dear Wales, enjoy these little morsels. They were very expensive. Love, Boris.”

The SNP’s manifesto, by contrast, is stern and direct. It is largely monochrome, clearly designed in opposition to the flashy, full-colour smarm of the Tory manifesto. Where the Conservatives have 30 photographs – eight of which feature Boris Johnson – the SNP use just seven photos in total, and only one of those is of Nicola Sturgeon. Her statement is written in short, unshowy sentences. It begins with: “This manifesto sets out how to build a better Scotland. It’s a manifesto to benefit this and future generations.” Ordinarily you’d say that repeating the word “manifesto” in two consecutive sentences was a weak style choice but I think that’s the point. The whole document is anti-style, anti-charm, anti-hyperbole, ie anti-Boris.

There is almost no imagery or metaphor. In its restraint, it sets itself apart. The clear message is that the SNP is a party that does not patronise its voters and – when you consider the Tory manifesto’s photo of Boris in an Iceland loading bay pretending he knows how to use a pallet jack – it’s hard to disagree.

The overall feel is minimalist, Scandinavian. Perhaps that’s intentional, indicating the hope that – sooner rather than later – Scotland can rip itself free from England and Wales and float off towards Sweden and Norway.