Terminal illness and the predictability of pie

How a twice-baked sour cherry pie helped one woman deal with her father's slow decline from ALS and eventual death.

by Hannah SelingerIt was June 2010 when I first encountered the pie recipe that would change my life. If you are wondering how I can possibly remember the moment in which I found the baked good that I did not even know I had been searching for, it is because of the exterior of my life, which was rattling around like old pennies in a pocket. My father was dying. The year before, he had been diagnosed with Lou Gehrig's Disease, otherwise known as ALS.

My father was only 56, but the year had been marked by the slow deterioration of this disease, which disrupts the communication between the brain and muscles. It starts, usually, with the extremities, rendering them useless, until it short-circuits every last neuron in the body. The mind persists, but the body, at the end stages, becomes completely paralysed. The disease had taken a man in his prime - an athlete, a father, a hands-on guy - and bent him until he curled. Right after his diagnosis, I left my job as a sommelier to help care for him. By the summer of 2011, he would be dead.

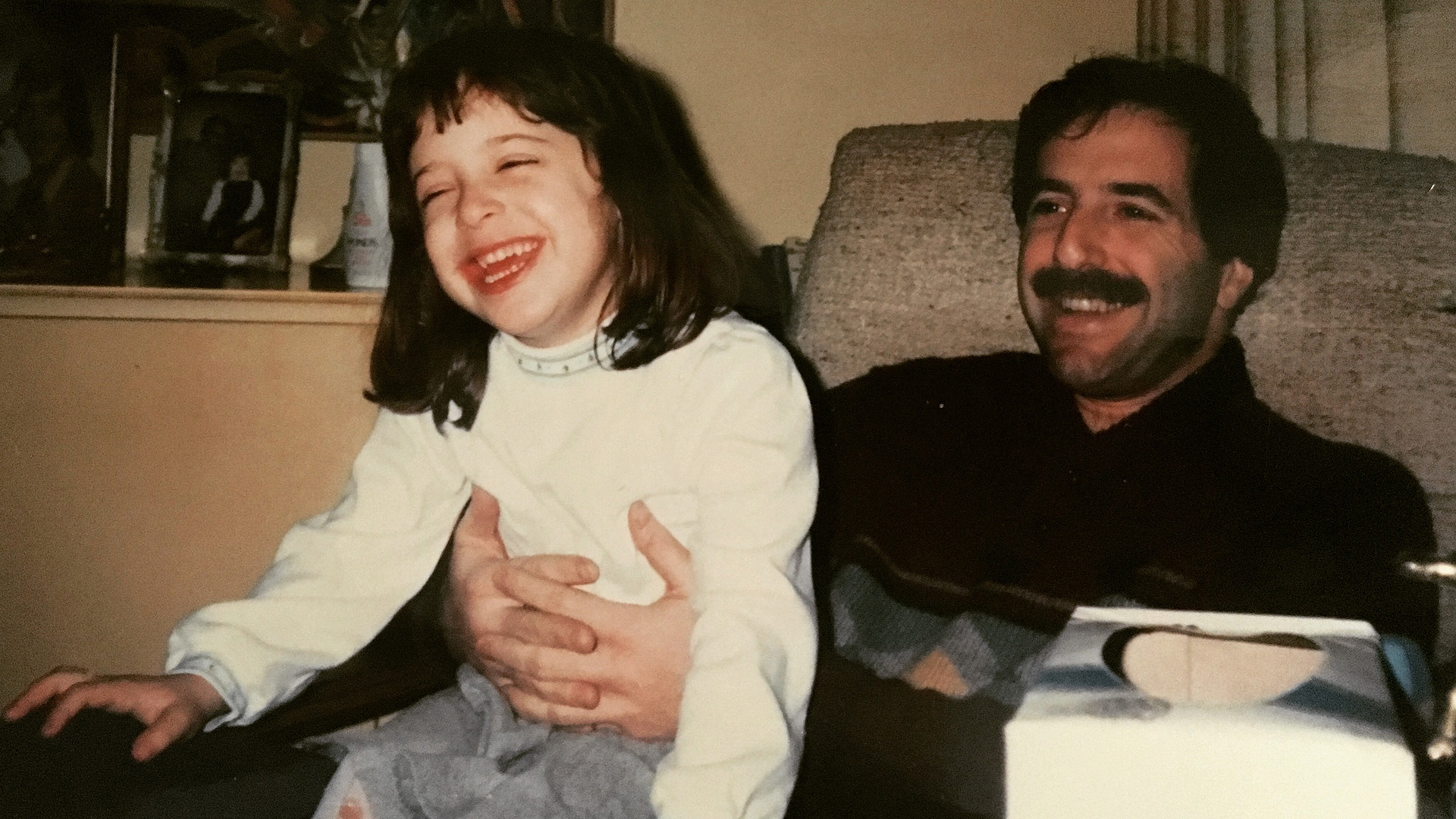

The writer as a child, with her father Neil Selinger [Photo courtesy: Emily Selinger]

Fighting a nagging depression brought on by a stagnant career, I spent countless hours in my New York galley kitchen, perfecting things that no one really wanted. I made ketchup, hot dog buns and mediocre chocolates. Sometimes, I cooked only for myself. I allowed myself to believe that cooking through grief was a mode of caretaking, but even my non-ambulatory father questioned my dedication to a pointless craft. "Heinz is just fine," he said when I produced a quart-sized container of ketchup that had taken me a day to create. He was diminishing, anyway, caring less and less about precociousness in the kitchen, the importance of which he had once emphasised. All of a sudden, he just looked tired.

I was tired, too. I was tired of wearing sweatpants in lieu of real clothes, of going nowhere besides the gym and the grocery store. I was tired of the burden of illness, and of the sinking around me, the widening depression in the earth that housed all of the things we had planned, our whole lives before us, all of it now gone.

But then, I discovered a pie.

It was a twice-baked sour cherry pie, and it stared up at me from the bruised pages of the weekend paper on a June afternoon. The newspaper's food section was something I looked forward to; it was aspirational for me, an escape to more delicious times. That Saturday, as I looked out into the dingy airshaft of my one-bedroom apartment, where I had lived for five years, I felt, for the first time in a long time, inspired.

Cherries peek out of golden pie crust in a sour cherry pie [Hannah Selinger/Al Jazeera]

In the photo, the crust was cut into overlapping circles, with molten cherries peering through, threatening to bubble over. I knew nothing of sour cherries. I did not know about their complexity, their short-lived season. But something in me opened up. Later that day, I took the subway into Manhattan. It had been a rainy June, not yet stifling, and from the elevated train I could see the city in her transformation: Green leaves where, just a few months before, the desolation of winter had reigned. At the sprawling Union Square Greenmarket, vendors were shifting gears into summer, their tents pulsing with produce.

I searched for cardboard pints and quarts of sour cherries, wended through the maze of the market, which takes up entire city blocks. I took my spoils home, and spread them out on the countertop like purloined jewels. They were beautiful, and firm, and there were a lot of them. You could not eat them plain, though I tried. The same quality that makes them so well suited for baking - their tartness - also makes them nearly inedible straight from the tree.

We begin meals with bread, and we end them with cake. The bakery is a way by which people connect. And by learning to bake pie, over and over again, my knuckles worn shiny like a washboard, I was learning to connect, too.

What is it about the physical act of baking that feels so rewarding? I have never much enjoyed getting my hands dirty. I do not like the slippery, squeamish feel of drippy eggs, or the squish of peeled tomatoes. In the kitchen, I fight the urge to wash my hands often. And yet, the act of baking - of stirring and kneading and cutting and scraping and binding together - brings me incomparable pleasure because, at day's end, when every mixing bowl is returned to the shelf and every vestige of strewn flour is erased from my kitchen, I have produced one thing that everyone loves.

Click for more from our series about food and what it says about the world we live in

It means something to cook for people, of course, something beyond the tangible and defined act of filling them with food and eliminating the biological problem of hunger. To cook for someone is to offer up a part of yourself - your time, yes, but also the magic of your imagination, of your desire to nurture. No doubt the magic of cooking dinner for a family is inextricably linked to this other magic, this baking magic. But baking offers up something else, too. It welcomes us in, and it breaks barriers down. We begin meals with bread, and we end them with cake. The bakery is a way by which people connect. And by learning to bake pie, over and over again, my knuckles worn shiny like a washboard, I was learning to connect, too. Not with people, necessarily, but with a version of myself that I had abandoned, a version of myself that had the ability to accomplish something - anything at all.

This pie. I think the reason why it was this pie, and not any other pie, was because of the punctuation of it. The confluence, really. I found it when I needed to find something - anything - to keep me afloat. I found it when I was busy trekking through the everyday meanderings of terminal illness, cataloguing the Hoyer lift that swept my father's sunken body into bed each night; and the Cough Assist that did the work that his own muscles once had by extricating phlegm from his lungs; and the catheter that slipped out one Saturday night when I was alone with him, thereby forcing me to my knees with towels and shame. These were the corporeal reminders of physical decline, and they were everywhere, haunting me, even in my sleep.

One pie's worth of cherries can take an hour to pit [Hannah Selinger/Al Jazeera]

A sour cherry, you should know, has a tiny window of brilliance. It fulfils its purpose for roughly one week a year, right before the 4th of July. In a good season, you might find quarts and quarts of sour cherries at the market, in fleshy ruby and deeper scarlet. Smaller than a quarter, they have a nearly translucent interior, so delicate that a traditional pitter will tear them apart. When I learned how to eat them, I learned how to pit them too - with an unfurled paperclip dug in to the centre and creating an invisible circle. Pop. A pie's worth of cherries might take an hour to pit. Maybe more. That time is time that does not count. It is motionless time, just one repetitive act, born over and over again, a rhythmic practice of love.

Did my father like the pie? It is hard to say. Toward the end of his life, he stopped liking much of anything. He had once been a gourmand, the man who introduced me to foie gras and to rolling cheese carts and to dim sum. I had, with him, my first ever sip of plum wine, my first ever taste of partridge. He taught me about crudo, and about New Jersey frozen custard served down on the boardwalk, about the great vintages of Bordeaux, and about the cuts of meat and how a sirloin was tougher - but better - than a filet. He loved simple things, like ripe plums, and mashed potatoes, and the sticky spareribs from mediocre Chinese restaurants. He preferred Pepsi to Coke.

But in the dim days that preceded his death, he stopped liking food in that same way. He stopped believing, I now think, that food could take care of him. He had cut back on culinary hedonism in his 40s, following a diagnosis of high cholesterol. In the following years, he toggled between medium-rare steaks (always sirloin, if he could help it) and wheat germ sprinkled over cantaloupe. Before the feeding tube went in, and after the doctors told him that he should eat more - more of everything, really, because he was beginning to lose weight - he became a child again, asking for banana milkshakes and pudding, for soft, sweet foods that he could still swallow. "I don't want to eat asparagus anymore," he told me one night. I did not argue. He was giving up on the discomforts that keep us comfortable. No more sunscreen. No more wheat germ. And, no: No more asparagus.

The writer's father at his college commencement at Columbia University in 1975 [Photo courtesy: Emily Selinger]

That is the difference, I guess, between foods that are good and foods that perform some other, less obvious function. Asparagus was not going to heal my father, and, frankly, neither was pie. But pie could at least put on a compelling performance. Pie could be a comfort, both to him and to me, a piece of art that stretched the sadness out of me and a contained dessert that my father could dig a fork into and still love.

Some months after that summer ended, my father stopped eating altogether. When the muscles in his throat stopped communicating with the neurons in his brain, food became a constant hazard, and so he went to the hospital and emerged with a hole in his stomach. From then on, he ate from a tube, his days as a gourmand suddenly and impossibly over.

And even though he could no longer eat, for the remainder of my father's life, I continued to find comfort in the predictability of piecrust. The chemistry of baking is finite. It was something I could rely on, something that did not confuse me, or creep up on me with the misanthropy of disease. ALS is mutable, but the combination of butter, flour, salt and ice water is not. My pies got better over time. For me, they were revelatory, a ladder out of grief, a concrete thing I could do that made both me, and the people around me, feel better. Baking pies in the face of immeasurable loss helped me climb back into my own life from the precipice of abyss. It was only a pie, you might say. But, to me, it was so much more.